The light is fading fast as I stand inside Tregeseal stone circle near St Just. The granite stones of the circle are luminous in this sombre landscape, like pale, inquisitive ghosts gathered round to see what we’re up to. Above us, a sea of withered bracken and gorse rises to Carn Kenidjack, the sinister rock outcrop that dominates the naked skyline. At night, this moor is said to be frequented by pixies and demons, and sometimes the devil himself rides out in search of lost souls.

Unbothered by any supernatural threat, we are gazing seawards, towards the smudges on the horizon that are the distant Isles of Scilly. The clouds crack open and a flood of golden light falls over the islands. My companion, archaeoastronomer Carolyn Kennett, and I gasp. It is marvellous natural theatre which may have been enjoyed by the people who built this circle 4,000 years ago.

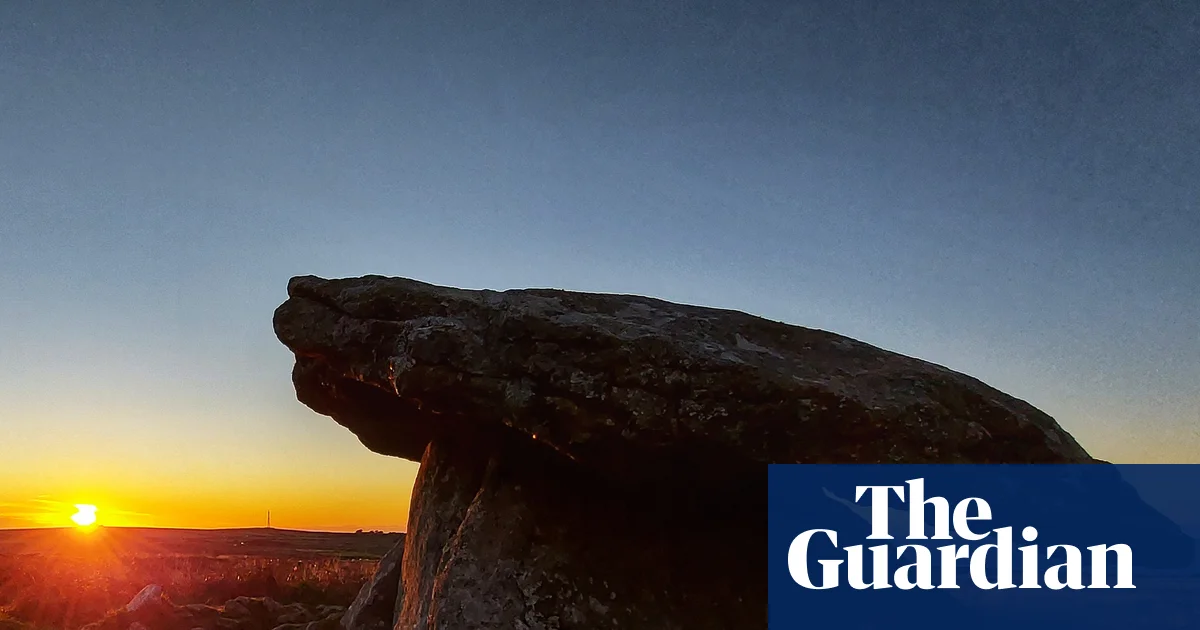

We have met at Tregeseal to talk about the winter solstice. Carolyn’s work focuses on the relationship of Cornwall’s prehistory with the sky, and she describes the whole Land’s End peninsula as an ancient winter solstice landscape. This, she says, is because of the spine of granite that runs south-west along the peninsula, towards the midwinter sunset. If, for example, you stand at winter solstice by Chûn Quoit – the mushroom-shaped burial chamber high on the moors south of Morvah – you will see the sun set over Carn Kenidjack on the south-western horizon. And likely this is exactly as Chûn Quoit’s Neolithic builders intended.

Carolyn suggests that Tregeseal stone circle was deliberately sited to allow people to view the midwinter sun setting behind the Isles of Scilly. “Seen from here, Scilly is a liminal space. On a clear day with high pressure, the isles look close up and just pop. On other days, they’re simply not there. The circle builders could have viewed Scilly as an otherworldly place, perhaps a place of the dead, associated with the winter solstice and the rebirth of the light.”

Where better to celebrate the return of the light than on the Land’s End peninsula, which points towards the setting point of the sun on the year’s shortest day?

We thread through the darkening russet moor past prehistoric burial mounds and heaps of mining slag to a mysterious monument, which may be the UK’s only ancient row of holed stones. Unlike the stone at Mên-an-Tol, their better-known sister a few miles away, it’s impossible to crawl through the Kenidjack holed stones; these holes are barely big enough to fit my hand through and very low to the ground. Archaeologists remain baffled.

Carolyn’s theory is that the row might have worked as a kind of winter solstice countdown calendar, with the rising sun shining through the holes from late October until December and creating varying beams of light in the stones’ shadows. “Feeling the warmth of that golden beam of sunlight in the cold, dark moor gave me a visceral experience of how prehistoric people might have perceived winter solstice,” she says.

Too many ancient sites are aligned to the rising or setting of the sun at midwinter or midsummer for it to be a coincidence. It makes sense that prehistoric farmers, who relied on the sun for light, warmth and the growth of crops, would want to track the sun’s movement. But in the 21st century, the darkness of this time of year still weighs on our spirits, and so we welcome the winter solstice, that darkest day of all before the hours of light begin to grow again. And where better to celebrate the return of the light than on the Land’s End (West Penwith) peninsula, which points towards the setting point of the sun on the year’s shortest day?

Montol revives the old Cornish custom of guise dancing, with its elaborate masks and costumes, traditional carolling and music of pipe, drum and fiddle

A bitter easterly is gusting, and eerie moaning rises from unseen cows as I tramp through soggy clover to pay a visit to the Boscawen-Ros stone, keeping watch as it has done for thousands of years above the peninsula’s south coast. It is just one of scores of prehistoric stones that stand alone or in pairs or circles all over the peninsula; less than a mile away are the famous Merry Maidens, dancers turned to stone for breaking the Sabbath. I think about how long the stone has persisted here, enjoying its view of the Celtic Sea and English Channel: where once Neolithic coracles would have floated, now the container ships and the Scilly ferry pass by.

Christopher Morris’s mesmerising film A Year in a Field, which documents 12 months in the life of this stone, draws attention to the power of its still and silent presence in the ever-changing landscape. “And I deliberately started and ended the film with winter solstice,” he tells me, “because it is a moment of pure hope – the promise of the ending of darkness and a bright new year ahead.”

On 21 December, all over West Penwith, people will be marking midwinter by walking to stone circles and holy wells, to hill forts and ancient beacons. Carolyn Kennett will be leading a guided walk to Chûn Quoit to observe the sun setting over Carn Kenidjack. Morris will walk to the Boscawen-Ros stone, as he does every winter solstice, in a sort of ritual of reflection and renewal. Later he, like thousands of others, will crowd into Penzance for Montol, a midwinter festival that dates only to 2007 but revives the very old Cornish custom of guise dancing, with its elaborate masks and costumes, traditional carolling and music of pipe, drum and fiddle.

Morris calls Montol “a wild night of misrule” – mischief and taboo-breaking are positively encouraged. The sun (in papier-mache form) will be set ablaze, while revellers disguised in animal masks, foliate heads or veils will dance triumphantly around it. There will be a herd of ’obby ’osses (hobby horses, including one called Penglaz and another called Pen Hood), dragons, fire-dancers and riotous merry-making. “A lot of sprout-throwing, too,” Morris adds. At 9.30pm those still standing will parade the Mock (the Yule log), flaming torches in hand, down Chapel Street to the sea. It is a fittingly uproarious and darkly magical celebration to welcome back the light.

In enchanted West Penwith, where rings of dancers were turned to stone and the witches once lit solstice fires in the moorland cromlechs, the tradition of folklore, storytelling and community ritual is still very much alive. And especially now, at midwinter.

Fiona Robertson is the author of Stone Lands, published by Robinson at £25. To support the Guardian buy a copy from guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply