Trump-Petro meeting: Just how icy are US-Colombia relations? | Drugs News

Donald Trump is expected to meet Colombian President Gustavo Petro on Tuesday after a year of exchanging insults and threats over the United States president’s aggressive foreign policies in Latin America, and Bogota’s war on drugs.

Petro’s visit to the White House in Washington, DC, on February 3 comes just one month after the US abduction of Venezuela’s President Nicolas Maduro in a lightning armed assault on Caracas.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

The Colombian leader will likely be seeking to address diplomatic tensions with the US, which have been in disarray since Trump began his second term last year.

The 65-year-old left-wing Petro has been a vocal critic of Trump’s foreign policies and recent military operations in the Caribbean Sea as well as of Israel’s war on Gaza – a thorny topic for the US president.

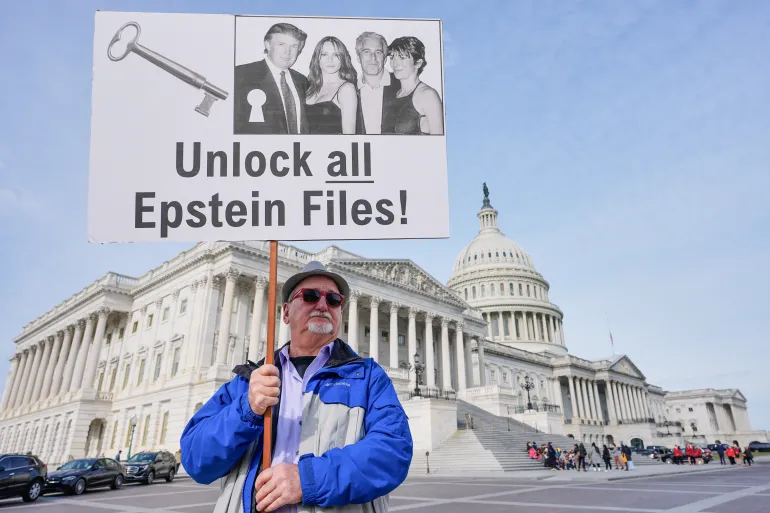

Last month, tempers rose again when Trump threatened to target Colombia militarily for allegedly flooding the US with illegal drugs.

Have relations between the two always been frosty?

No. After Colombia gained independence from Spain in 1819, the US was one of the first countries to recognise Colombia’s independence in 1822. It established a diplomatic mission there in 1823.

A year later, the two nations signed a string of treaties focusing on peace, navigation and commerce, according to US government archives.

Since then, the two nations have continued to cooperate on security and economic matters. But these efforts have been interrupted at times, such as during the Cold War, by geopolitics and in relation to Colombia’s war on the drug trade.

Here is a timeline of key issues and events.

Business interests threatened

In 1928, US businesses were operating in Colombia. But their interests were threatened when Colombian employees of America’s United Fruit Company protested, demanding better working conditions. Political parties in Colombia had also begun questioning Washington’s expanding role in Latin America following these protests.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), this was also the period of the “Banana Wars” when Washington was busy toppling regimes in South America to shore up its business interests in the region.

A string of US military interventions took place from 1898 to 1934 as Washington sought to expand its economic interests in the region until President Franklin D Roosevelt introduced the “Good Neighbor Policy”, pledging not to invade or occupy Latin American countries or interfere in their internal affairs.

Emergence of FARC

Security relations between the US and Colombia deepened during the second world war. In 1943, Colombia offered its territory for US air and naval bases while Washington provided training for Colombian soldiers.

According to the CFR, the US boosted military support for Colombia during its deadly conflict with armed rebel groups, which lasted from 1948 until the mid-1950s and killed more than 200,000 people. During this conflict, many independent armed groups emerged in the countryside, and the US implemented a strategy known as Plan Lazo to improve civilian defence networks.

In response, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) was formed by rebel leaders and engaged in widespread violence and kidnappings, according to the CFR.

FARC claimed to be inspired by communist values and, in the late 1940s, controlled about 40 percent of the country, according to the CFR. Washington labelled it as a “terrorist” organisation and focused efforts towards destabilising the group.

FARC eventually signed a peace agreement with the Colombian government in 2016. In 2021, the group was delisted from Washington’s foreign terrorist organisations’ list.

War on drugs

As FARC was rising in Colombia, the drug trade was also gathering momentum. Groups such as the Medellin Cartel and Cali Cartel emerged in the country, and trafficked marijuana and cocaine to the US on a regular basis.

Faced with a rising number of drug-related deaths, the US government spent more than $10bn on counter-narcotics and security efforts to aid Colombia’s government between 1999 and 2018, according to a US Government Accountability Office report.

Former US presidents, including Bill Clinton and George W Bush, also launched counter-narcotic initiatives to disrupt drug trafficking, destroy coca crops, and support alternative livelihoods for coca farmers, in a bid to quash the cartels.

Trump’s first term as president, beginning in 2017, was marked by renewed counter-narcotic initiatives but he also threatened to decertify Colombia as a cooperative country if it did not take action against its drug cartels.

Tensions between the US and Colombia calmed under former US President Joe Biden, who focused on improving diplomatic ties by designating Colombia as a major non-NATO ally in 2022.

Today, cartels function in a decentralised manner and some have also been designated as terrorist organisations by the US. In December 2025, the Trump administration designated the Gulf Clan, Colombia’s largest illegal arms group, which is also involved in drug trafficking, as a terrorist organisation.

Trump’s second term

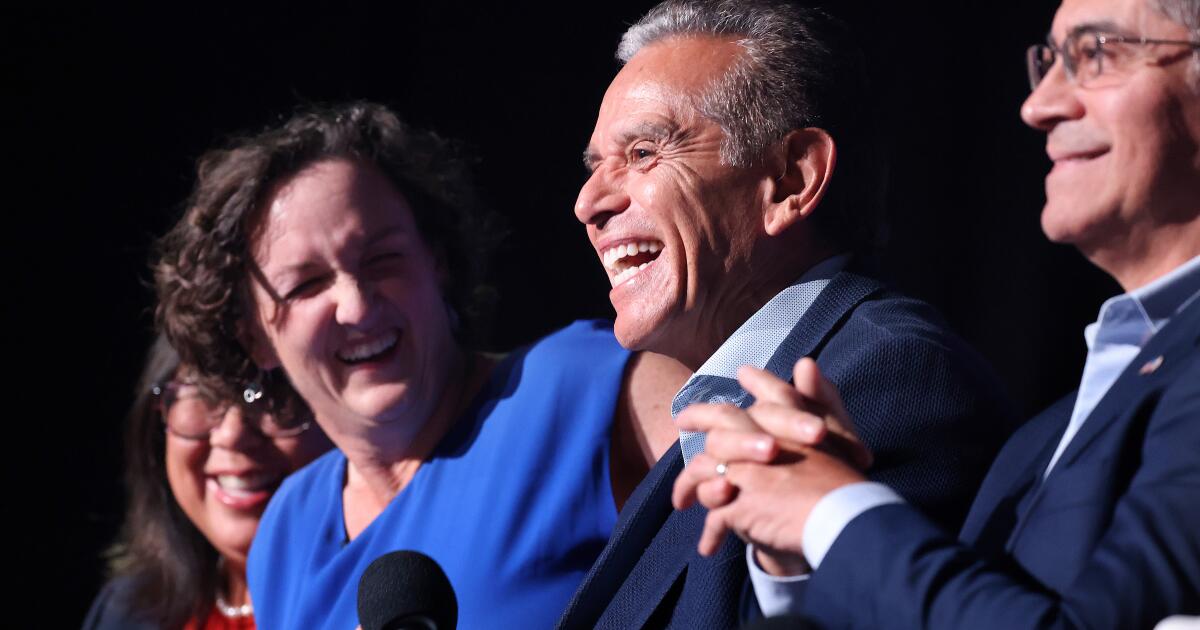

In 2022, Petro was elected as Colombia’s first left-wing president and took up office in the presidential palace with promises to lead Colombia in a more equitable, eco-friendly direction.

But tensions with the US flared again when Trump arrived in the White House for his second term in January 2025.

Since then, Petro has been a vocal critic of Trump’s policies, particularly those relating to Latin America.

Last year, the Trump administration began a series of military strikes on Venezuelan boats, which it alleged were carrying drugs, in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific. The Trump administration has struck dozens of boats, but has not provided any evidence that any were trafficking drugs. Petro called the aggression an “act of tyranny”.

Addressing the United Nations General Assembly in September 2025, Petro said that “criminal proceedings must be opened against those officials, who are from the US, even if it includes the highest-ranking official who gave the order: President Trump”, in relation to the boat strikes.

At the UNGA, Petro also criticised US ally Israel’s war on Gaza and called on US troops to “disobey Trump’s orders” and “obey the order of humanity”.

Washington revoked Petro’s US visa after he spoke at a pro-Palestine march outside the UNGA in New York.

Weeks later, the Trump administration also imposed sanctions on the Colombian president, who is set to leave office following a presidential election in May.

In a post on his Truth Social platform in October, Trump said Petro “does nothing” to stop the drug production [in his country], and so the US would no longer offer “payment or subsidies” to Colombia.

Shortly after carrying out the abduction of Venezuela’s Maduro, Trump told reporters on board Air Force One that both Venezuela and Colombia were “very sick” and that the government in Bogota was run by “a sick man who likes making cocaine and selling it to the United States”. “And he’s not going to be doing it very long. Let me tell you,” Trump added.

When asked if he meant a US operation would take place against Colombia, Trump said, “Sounds good to me.”

In response, Petro promised to defend his country, saying that he would “take up arms” for his homeland.

In an interview with Al Jazeera on January 9, however, Petro said his government is seeking to maintain cooperation on combating narcotics with Washington, striking a softer tone following days of escalating rhetoric.