Our pendulum of hope and frustration oscillated with particular violence in 2025. We went from seeing Nicolas Maduro and his dictatorship acting with total impunity to being—apparently—threatened by the biggest military force in the world, the US armed forces. However, the year is ending with the typical bitterness of a Maduro Christmas: asphyxiating inflation, empty airports, and painful video calls across continents, with the addition of an uncertainty about 2026 that feels more blurry than ever. Hyperinflation is threatening a comeback, migration remains as an escape valve, and we’re forced to struggle with assessing the likelihood and potential effects of an unprecedented scenario such as an American military intervention. We might need more rum than usual in tonight’s ponche crema.

The January of dispair

2025 started with a January of traumatic disappointments. An opposition demonstration in Caracas and other cities on January 9th showed little turnout, perfectly understandable after months of unprecedented state terror following the theft of the presidential election by the Maduro regime. The main event was the dramatic reappearance of Maria Corina Machado, who was in hiding since August 2024, followed by the news of her being kidnapped for some hours by chavista goons. On this very opaque incident, when she was forced to record a video from a park in Caracas, we still feel the complete story is yet to be told. Machado was physically attacked and threatened, making everyone aware that not even her was safe from a dictatorship that is no longer disguising but exposing its cruelty. Soon, that message would be underlined by the disappearance of the candidate that represented the “center” in the election, Enrique Marquez, who dared to defy the Supreme Court about its contribution to the fraud. Marquez was recently released but has remained silent since then. Also, the regime took president elect Edmundo Gonzalez Urrutia’s son in law, Rafael Tudares, who remains in jail and isolated to this date.

Then, on January 10th, it was clear that Gonzalez Urrutia’s promise about returning to Venezuela was impossible to accomplish. Maduro took oath for a second illegitimate term in a hall of the Legislative Palace, smaller than the one when presidents used to celebrate their inauguration, but even with that modest ceremony he made evident that the world was unable or unwilling to punish him for stealing the election, and that once again the armed forces decided to keep supporting the Bolivarian Revolution, as they had done in every crossroads since the failed coup of April 2002.

Maduro got away with it, one more time.

The betrayal of El Catire

A few days after Maduro’s inauguration, Trump had his own, also in an unconventional venue inside the Capitol, and signed a barrage of executive orders that signaled the tempo of T2. Trump’s new term went in sync with the hateful discourse on Venezuela he advanced during the campaign, and not with the hopes of Venezuelans in the US. A tweet from one of those popular and deeply irresponsible Venezuelans that spread nonsense in social media, as proven by this investigation, led Trumpism to embrace the narrative that Venezuelan migrants are weapons sent by Maduro to infect the US, which led to the removal of TPS for around 600,000 Venezuelans.

While he charged against migrants, Trump sent a special envoy, Richard Grennell, to greet Maduro and Jorge Rodriguez in Miraflores Palace. They made a deal: in exchange for the release of ten prisoners with American citizenship (including a Venezuelan accused of killing three people in Madrid) and the renewal of the operating license for American oil company Chevron, Maduro would take deportees in chartered flights from the US. Trump would also send almost 300 Venezuelans to the CECOT megajail in El Salvador and even the infamous Guantanamo, where they were treated as terrorists even when few of them had ties with Tren de Aragua (the infamous Venezuelan transnational gang) or committed any serious crime. The Venezuelans in CECOT would be eventually shipped to Venezuela. They and their families were traumatized; Machado and Gonzalez Urrutia only asked to respect due process (which did not happen); and both Trump and Maduro won: the first by looking as being tough on crime, the latter by greeting the deportees in the Maiquetia tarmac as a good dad that welcomes home the victims of imperialism.

One landmark to explore in this story: the shattering of a century-long fascination with the US by many Venezuelans, who are now seeing that the country they aspired to live in and prosper is suddenly treating us as pariahs.

The flight of the guacamayas

The idea of tolerating and normalizing Maduro was confirmed in May with the parliamentary election that served to assign new roles to people coming from the opposition. Besides the group of the faux opposition—those who rebelled in 2017 against the leadership of Accion Democratica, Primero Justicia and Voluntad Popular and took part in stealing those party brands with Maduro’s SUpreme Court—the May election produced a new kind of co opted opposition, led by no other than Henrique Capriles. Along with Stalin Rivas and Juan Requesens (this one a special case that deserves his own story), Capriles went back to square one of his political career, being a lawmaker, this time not against chavismo but subordinated to it, as the new face of the “good opposition” that Maduro used to show to the rest of the world as proof of his democratic tolerance. Capriles embraced the anti-sanctions rhetoric, criticizes Machado and claims for continuing the electoral path after the massive fraud of 2024 even before actually seating in the National Assembly, which is supposed to happen in a few days.

May 2025 also saw another big development in the real opposition: the escape of the Machado team that was under siege in the Argentina embassy. The breakout humiliated Diosdado Cabello’s repressive apparatus and made even more visible how useless Lula is, given that Brazil was supposedly in charge of the embassy after Caracas broke diplomatic liaisons with Buenos Aires. It gave Machado’s very disciplined team the ability to move at ease in the world, lobbying with the Trump administration and coordinating the plans for the “day after.”

Looking at the sky

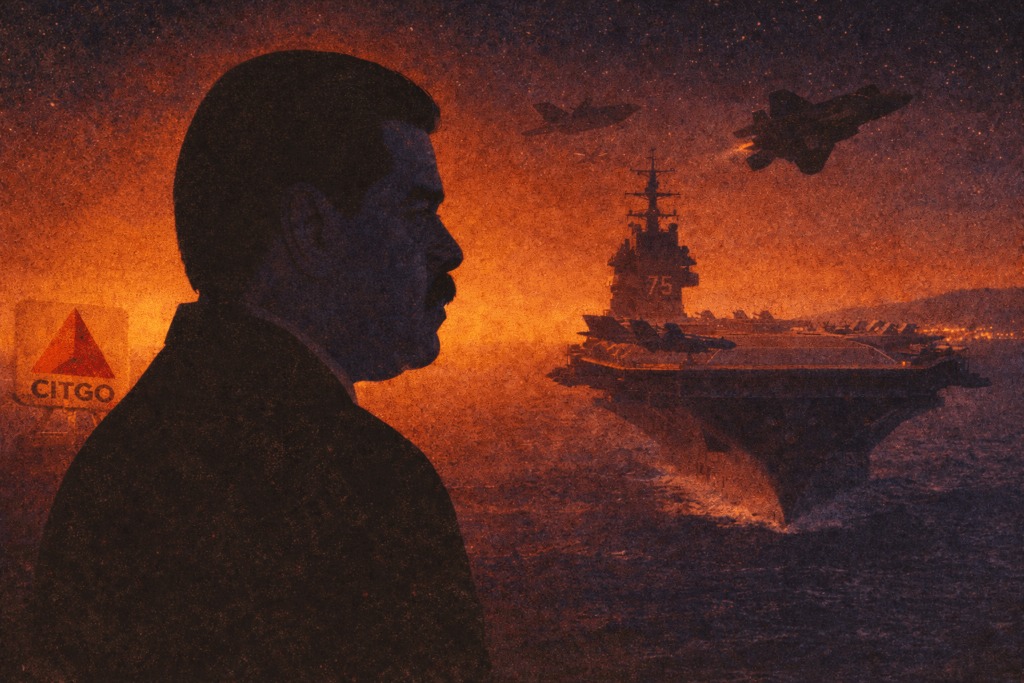

The climate changed dramatically in August with a Reuters scoop saying that the Southern Command started a naval deployment in front of Venezuelan waters just after the US increased the rhetoric against Maduro, Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua. Without interrupting the Chevron operation in Venezuela and the deportation flights, warships and planes actually began to accumulate in Puerto Rico and other islands, while Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana and other pro-Trump governments offered assistance to the US in its fight against the drug trafficking and the security concerns represented by the chavista regime.

It looked like suddenly Trump had changed his mind about leaving Maduro be, or rather listened to Marco Rubio’s plan of toppling chavismo to make Cuba and all the Latin American left collapse. It also seemed a casus belli was in the making, with some international support. The US discourse would lean harder—helped by years of indictments and sanctions by previous Democrat and Republican administrations—on the the designation of Maduro as chief of Cartel de los Soles and Tren de Aragua, and therefore the leader of two criminal organizations considered terrorists by the US.

In September, a video revealed the bombing of a boat that according to the US was shipping drugs from Venezuela to Trinidad. Eleven Venezuelans were killed.

Next, more boats manned by unknown civilians were attacked (and continue to be targeted in the Caribbean and the Pacific Ocean) and the Southern Command populated the sea with drones, war planes, a submarine, more warships and the USS Gerald Ford. Some of us became addicted to OSINT tweets about F35s and B52s patrolling the borders of Venezuelan airspace, closer and closer, and even drawing obscene radar traces in the map. At the same time, the total lack of due process in the attack on boats, and the weaknesses of the narrative against Maduro as a narco instead of the enabler of crimes against humanity he really is, increased the pressure on Trump from Democrats, some Republicans and pundits with different interests and motivations across whole world. The Monroe Doctrine and gunboat diplomacy have returned, they say. Maduro, of course, activated the only defense he really has against such a threat: posing his regime as a victim of imperialism, and making dozens of media outlets write headlines about the millions of militia men he raised to fight an American invasion, ignoring the fact that milicianos are mostly senior citizens trying to survive and that the only thing that the armed forces are doing is watching among themselves in search of traitors, and increasing the repression on their hostages: Venezuelans in Venezuela.

We got used to looking at the sky, not only to see if a missile was coming on Fuerte Tiuna. The canonization of two Venezuelan saints in October was an opportunity for the new Pope to criticize Maduro, but the miracle that Machado kind of promised did not happen either. The day of the canonization there were no demonstrations against the regime in Venezuela. Maduro cancelled the big event he had scheduled in the Monumental stadium. The Church focused on the religious character of the event, but even so, cardinal Baltazar Porras would be harassed and get his passport confiscated.

The Nobel

Everyone was discussing whether Trump would get his deeply desired Nobel peace prize when we were surprised by the news that the winner was no other than Maria Corina Machado—although she dedicated the award to Trump.

Actually, the Nobel became a new case of foreigners using our tragedy to play the moral high ground in their respective political arenas, like the Colombian writers who refused to take part in the Hay Festival in Cartagena de Indias next January because Machado was also invited. The same people that could accept invitations from chavismo and ignore the international reports of continuing human rights violations, issued by the researchers of the International Crime Court or the UN Fact Finding Mission who just closed their offices in Venezuela given the absolute lack of cooperation from the dictatorship.

Even with that noise around, the prize served to turn part of the attention to the main story behind it, the effort made by thousands of volunteers to win the election and prove that Maduro stole it. The two powerful speeches read during the ceremony in Oslo reminded the world the real nature of what Venezuelans are going through, by mentioning for instance the death in custody of former Nueva Esparta governor Alfredo Diaz, a landmark in repression during the chavista era. That December 10 culminated in the arrival of Maria Corina, after hours of disturbing uncertainty on her whereabouts. She had managed to escape the siege and now was out in the world, with increased maneuvering range. That same day, the US announced it had seized a tanker shipping Venezuelan oil to Cuba, making December 10th the worst day Maduro had since July 28, 2024, and opening new questions.

Still waiting on the gringos

The main question we’re asking ourselves at the end of 2025 is whether the US will ever make a direct attack on the chavista regime. Has Trump decided to push Maduro out just by showing the weapons but refraining from using them on FANB, ELN or FARC dissidents on Venezuelan soil?

We really don’t know. Maybe all that naval deployment is just about changing the American geopolitical doctrine and replenishing the Americas of military assets to reassert dominion in the “Latin American backyard.” Maybe Trump’s plan (assuming he has any) is to break the regime with an oil blockade.

What we do know is that Trump is mistaken if he expects that the chavista regime would break without a clear, unquestionable threat to their personal safety.

The Venezuelan drama has many similarities with a hostage crisis. Maduro & Co. are a gang assaulting a bank branch and depleting its vault while holding the clients and personnel kidnapped; SWAT arrived, but instead of storming the bank after so many negotiators had failed, they decided to cut the food supply. The chavista regime can endure that by transferring all the hunger to the hostages; they have done it before. In the meantime, another negotiator with a savior complex may appear to attend the “political crisis.”.

Marco Rubio said that Maduro would not play with Trump as he did with Joe Biden. But that is precisely what Maduro is doing so far, waiting out this new threat. So far, the US president is bluffing. He had issued several vague threats, but during T2 he has never really made a commitment to remove Maduro and induce a regime change in Venezuela. His speech against Maduro and Venezuelans can stretch well into the next year, keeping him (and us) as scapegoats and villains in a story about the pure American race being polluted by a foreign evil.

2026: another level of uncertainty

Just after Trump said something very vague about destroying a port in Venezuela on Christmas eve, CNN claimed that the CIA executed a drone strike on a beach used by Tren de Aragua to export drugs—not a chemical plant in Maracaibo as it was though because of OSINT reports in social media—, with no victims. We have no details, but if this is true, this implies the first clear violation of Venezuelan sovereignty by the US, a historical landmark and a hint that the whole thing could escalate into bombing military facilities and spread chaos within the regime.

Our assessment is that the panic wave necessary to push the chavista elite to eat itself and collapse must not be taken for granted, due to the resilience of the regime and the dependency on Trump’s decision-making. Not even a dramatic cut of oil income because of the pressure on oil tankers will necessarily bring down the dictatorship in the short term.

Polls in the US indicate that attacking Venezuela is not in fashion. Trump has already started to pay a political price without making a dent in the chavista alliance. On the contrary, a criminal like Maduro is being defended by the global left and Cabello is gaining more and more power as the Great Inquisitor. The regime released dozens of political prisoners, but retained those of strategic importance, and with Machado out, the opposition was deprived of its more significant leader in the country.

Time is running out for the increasingly unpopular Trump, who must take care of the midterm election in 2026, and for Marco Rubio, who might leave the cabinet to run for Florida governor. Time is helping Maduro and Cabello, whose only goal is to remain in power day after day.

Common Venezuelans, on their part, continue to see how everyone speaks on their behalf without considering their opinion, or the fact that they are prohibited to express it. More than geopolitics or Trump’s polls or CIA drones or the USS Gerald Ford, they are worried by the exchange rate and the luring of hyperinflation. All this uncertainty and the fall of oil income will make their lives harder.

However, 2026 could be the year when the US increases pressure to the point that the regime breaks and a democratic transition starts. It still is a possibility. We must hope for the best, without blinding ourselves to the challenges of reality and the unstable nature of the guys who can define the outcome.