Who is Lee Jae-myung, South Korea’s new president? | Politics News

Lee Jae-myung’s hardscrabble path to the South Korean presidency mirrors his country’s stratospheric rise from grinding poverty to one of the world’s leading economies.

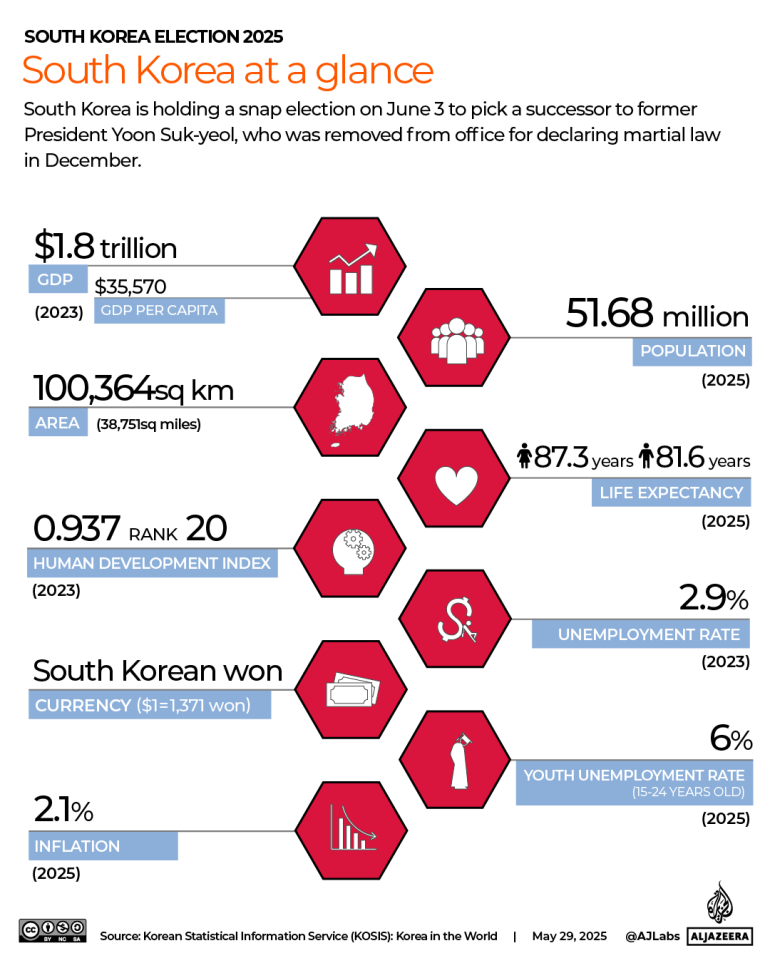

When Lee, a scandal-prone school dropout-turned-lawyer who was elected in a landslide on Tuesday, was born in 1963, South Korea’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was comparable with sub-Saharan African nations.

South Korea was so poor, in fact, that Lee’s exact birthday is a mystery – his parents, like many families alert to the sky-high infant mortality of the era, took about a year to register his birth.

Yet even by the standards of the day, Lee’s early years were marked by deprivation and adversity, including stints as an underage factory labourer.

Known for his populist and outspoken style, Lee, the standard bearer for the left-leaning Democratic Party, has often credited his humble beginnings with moulding his progressive beliefs.

“Poverty is not a sin, but I was always particularly sensitive to the injustices I experienced because of poverty,” Lee said in a speech in 2022.

“The reason I am in politics now is to help those still suffering in the pit of poverty and despair that I managed to escape, by building a fair society and a world with hope.”

The fifth of seven children, Lee dropped out of school in his early teens to move to Seongnam, a satellite city of Seoul, and take up employment to support his family.

At age 15, Lee was injured in an accident at a factory making baseball gloves, leaving him permanently unable to straighten his left arm.

Despite missing years of formal education, Lee graduated from middle and high school by studying for the exams outside of work hours.

In 1982, he gained admission to Chung-Ang University in Seoul to study law and went on to pass the bar exam four years later.

During his law career, Lee was known for championing the rights of the underdog, including victims of industrial accidents and residents facing eviction due to urban redevelopment projects.

In 2006, Lee made his first foray into politics with an unsuccessful bid for the mayorship of Seongnam, which he followed two years later with a failed run for a parliamentary seat in the city.

In 2010, he finally broke into politics by winning Seongnam’s mayoral election on his second attempt and went on to earn re-election four years later.

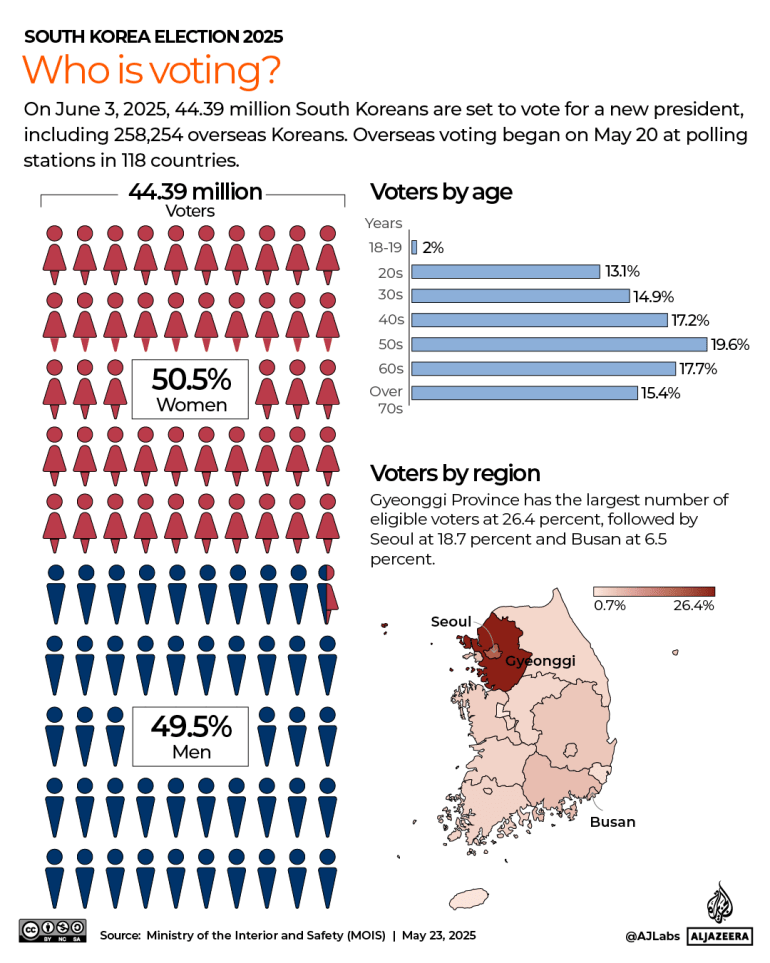

From 2018 to 2021, Lee served as governor of Gyeonggi, the country’s most populous province, which surrounds Seoul.

Both as mayor and governor, Lee attracted attention beyond his immediate electorate by rolling out a series of populist-flavoured economic policies, including a limited form of universal basic income.

After stepping down as governor, Lee entered the national stage as the Democratic Party candidate in the 2022 presidential election, which he lost to Yoon Suk-yeol by 0.73 percent of the vote – the narrowest margin in South Korean history.

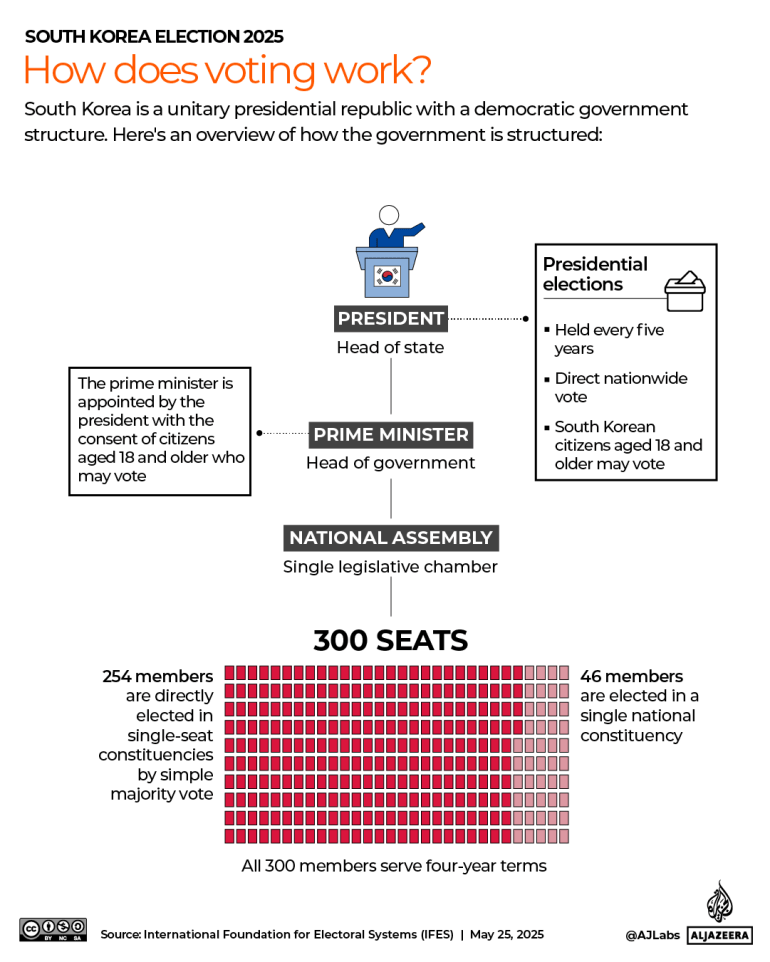

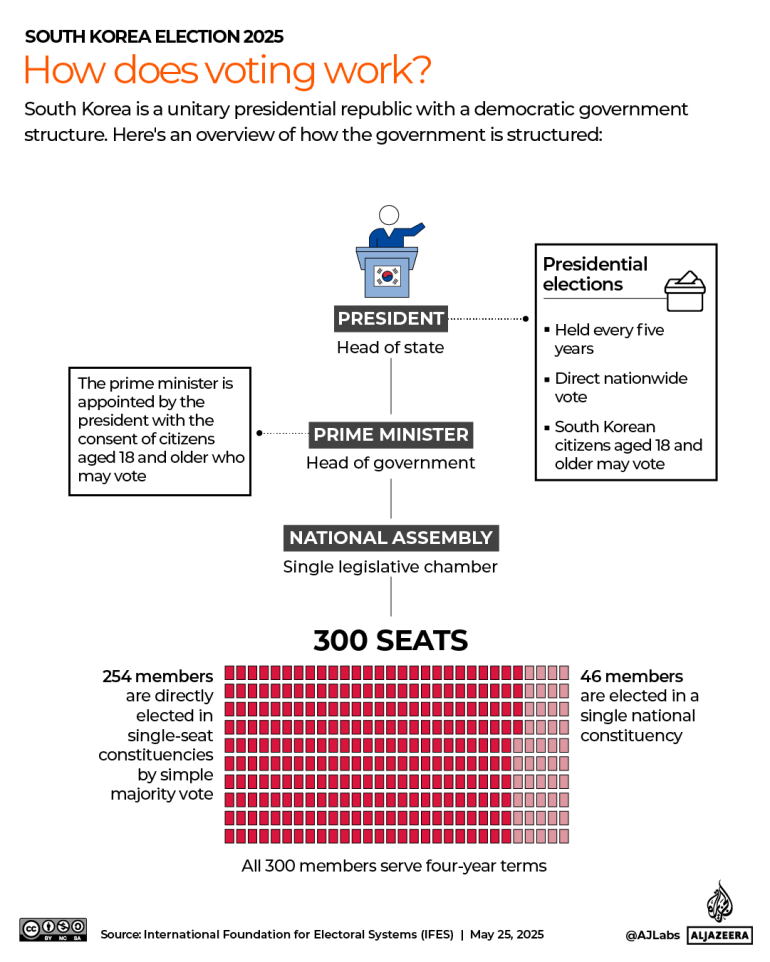

Despite facing a slew of political and personal scandals, culminating in at least five legal cases, Lee led the Democratic Party to one of its best results in last year’s parliamentary elections, delivering it 173 seats in the 300-seat National Assembly.

After Yoon’s impeachment and removal from the presidential office following his short-lived declaration of martial law in December, Lee earned his party’s nomination without serious challenge, garnering nearly 90 percent of the primary vote.

“His communication style is direct and straightforward, and he is astute at recognising social and political trends, which is a rare quality among politicians of his generation in Korea,” Lee Myung-hee, an expert on South Korean politics at Michigan State University, told Al Jazeera.

“However, this direct communication style can sometimes hinder his political advancement, as it may easily offend his opponents.”

During his election campaign, Lee played down his progressive credentials in favour of a more pragmatic persona and a milder iteration of the populist economic agenda that powered his rise to national prominence.

In the weeks leading to the vote, Lee’s victory was rarely in doubt, with his closest competitor, Kim Moon-soo, of the conservative People Power Party, often trailing the candidate by more than 20 points in opinion polls.

‘A progressive pragmatist’

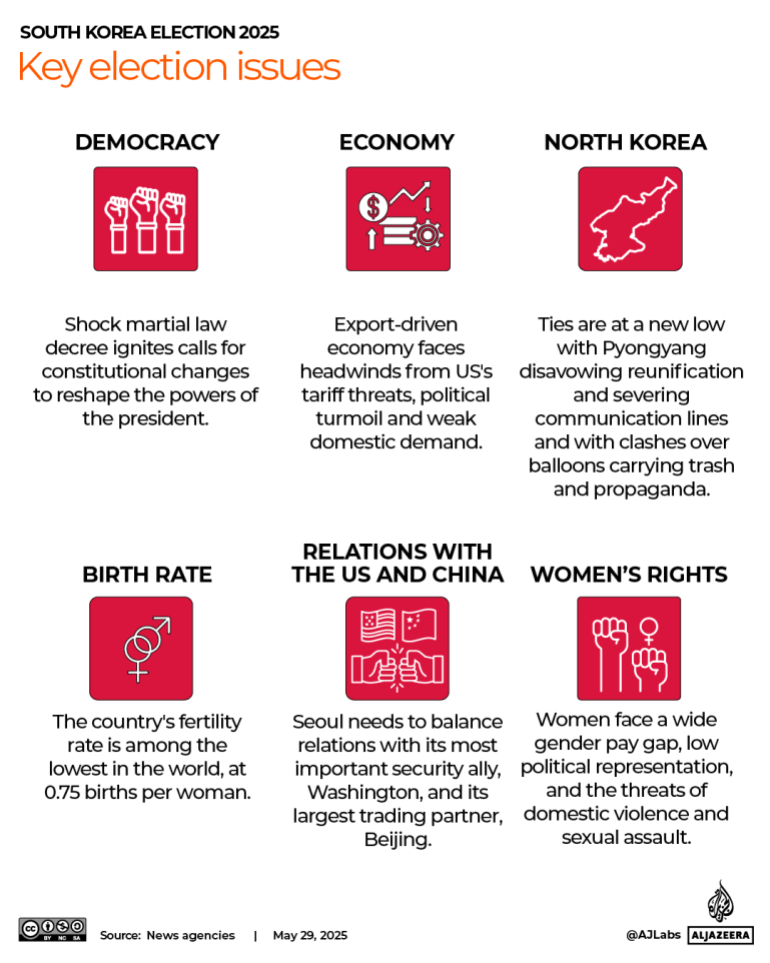

As president, Lee has pledged to prioritise the economy, proposing, among other things, a major boost in investment in artificial intelligence, the introduction of a four-and-a-half-day work week, and tax deductions for parents in proportion to the number of children they have.

On foreign affairs, he has promised to mend relations with North Korea while pushing for its ultimate denuclearisation – in keeping with the traditional stance of his Democratic Party – and maintain the US-Korea security alliance without alienating China and Russia.

“I would call him a progressive pragmatist. I don’t think he will stick to any consistent progressive lines or even conservative lines,” Yong-chool Ha, director of the Center for Korea Studies at the University of Washington, told Al Jazeera.

“Critics call him a kind of manipulator; his supporters call him flexible,” Ha said.

“I would say he is a survivor.”

While Lee will enter office with the backing of a commanding majority in the National Assembly, he will take stewardship of a country that is deeply polarised and racked by divisions following Yoon’s impeachment.

“The Korean political landscape remains highly polarised and confrontational, and his ability to navigate this environment will be crucial to his success,” said Lee, the Michigan State University professor.

Lee will also have to navigate a volatile international environment shaped by the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, great power rivalries, and United States President Donald Trump’s shake-up of international trade.

For Lee personally, his election, after two unsuccessful bids for the presidency, marks an extraordinary comeback befitting the against-the-odds origin story that propelled his rise.

Lee had been facing five criminal proceedings, including charges of election law violations and breach of trust in connection with a land corruption scandal.

Following his election, Lee is all but certain to avoid trial during his five-year term in office.

Under the South Korean constitution, sitting presidents enjoy immunity from prosecution, except in cases of insurrection or treason – although there is debate among legal scholars about whether the protection extends to proceedings that are already under way.

To remove ambiguity, the Democratic Party last month passed an amendment to the criminal code stating that criminal proceedings against a person who is elected president must be suspended until the end of their term.