Column: Trump’s 626 overseas strikes aren’t ‘America First.’ What’s his real agenda?

Who knew that by “America First,” President Trump meant all of the Americas?

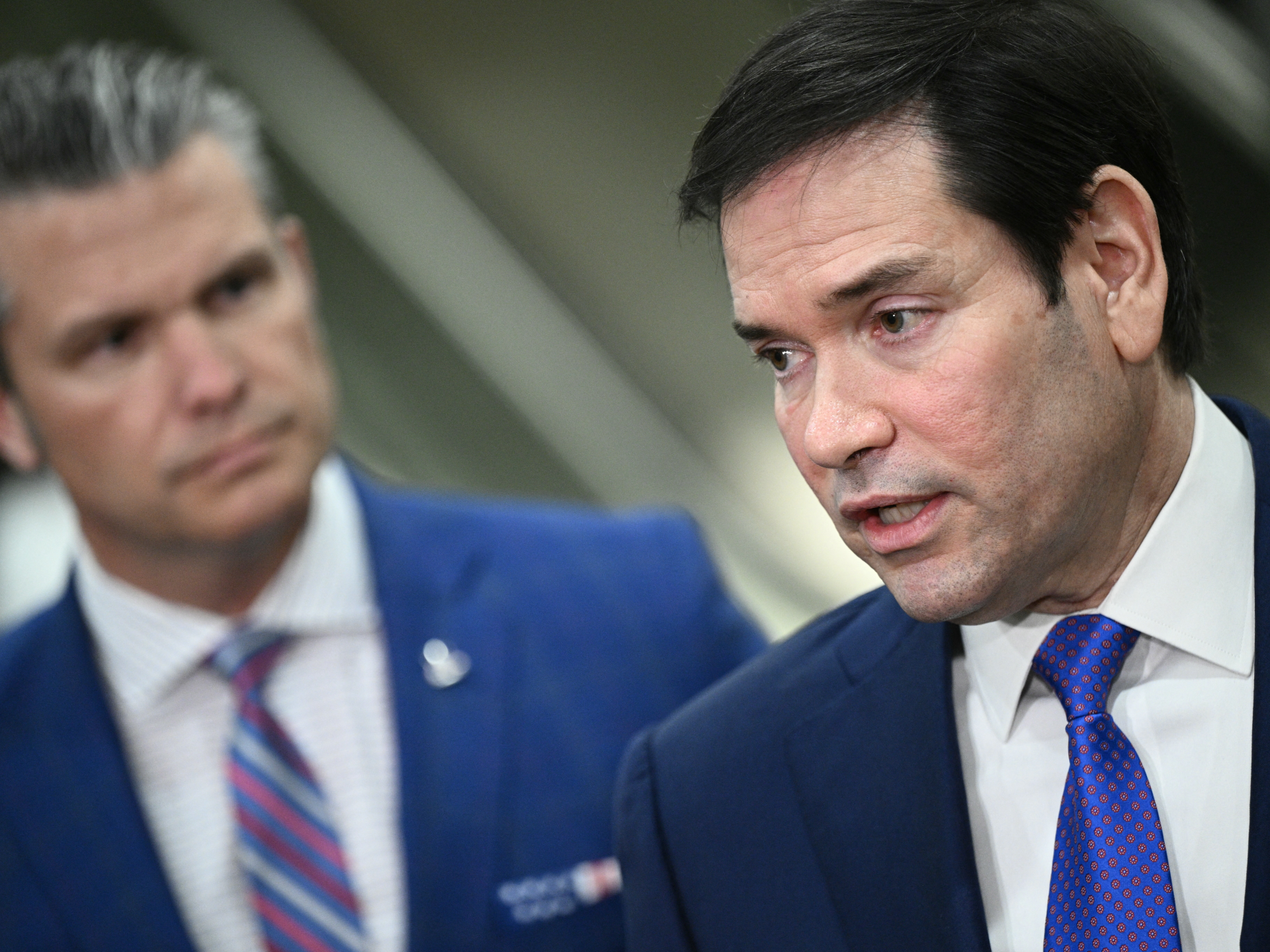

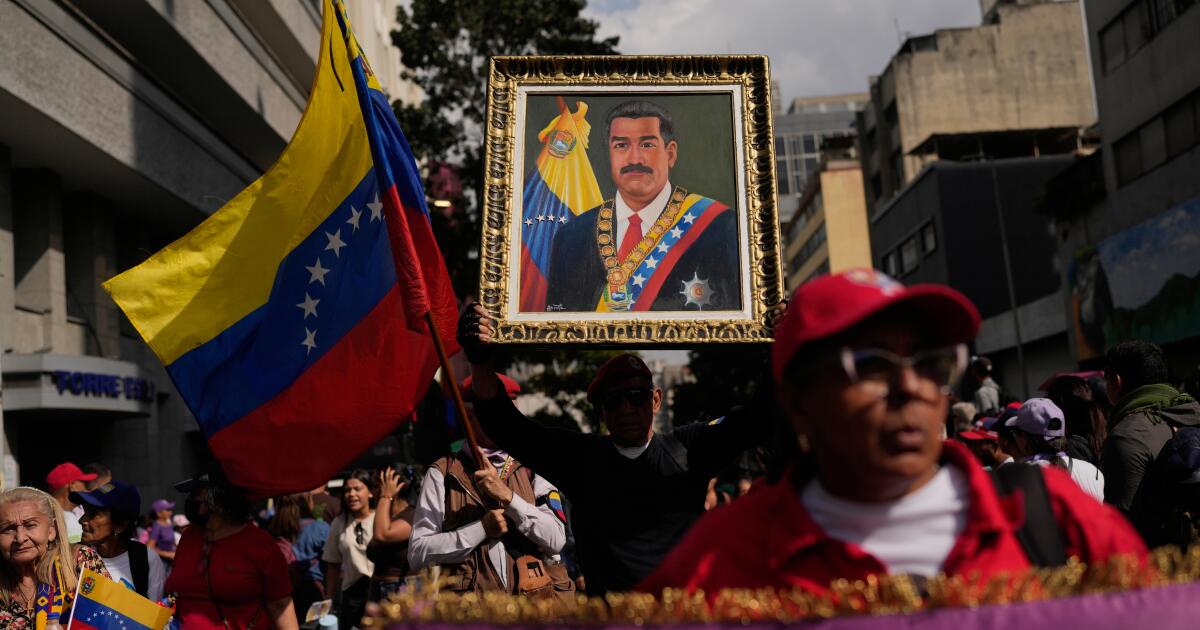

In puzzling over that question at least, I’ve got company in Marjorie Taylor Greene, the now-former congresswoman from Georgia and onetime Trump devotee who remains stalwart in his America First movement. Greene tweeted on Saturday, just ahead of Trump’s triumphal news conference about the United States’ decapitation of Venezuela’s government by the military’s middle-of-the-night nabbing of Nicolás Maduro and his wife: “This is what many in MAGA thought they voted to end. Boy were we wrong.”

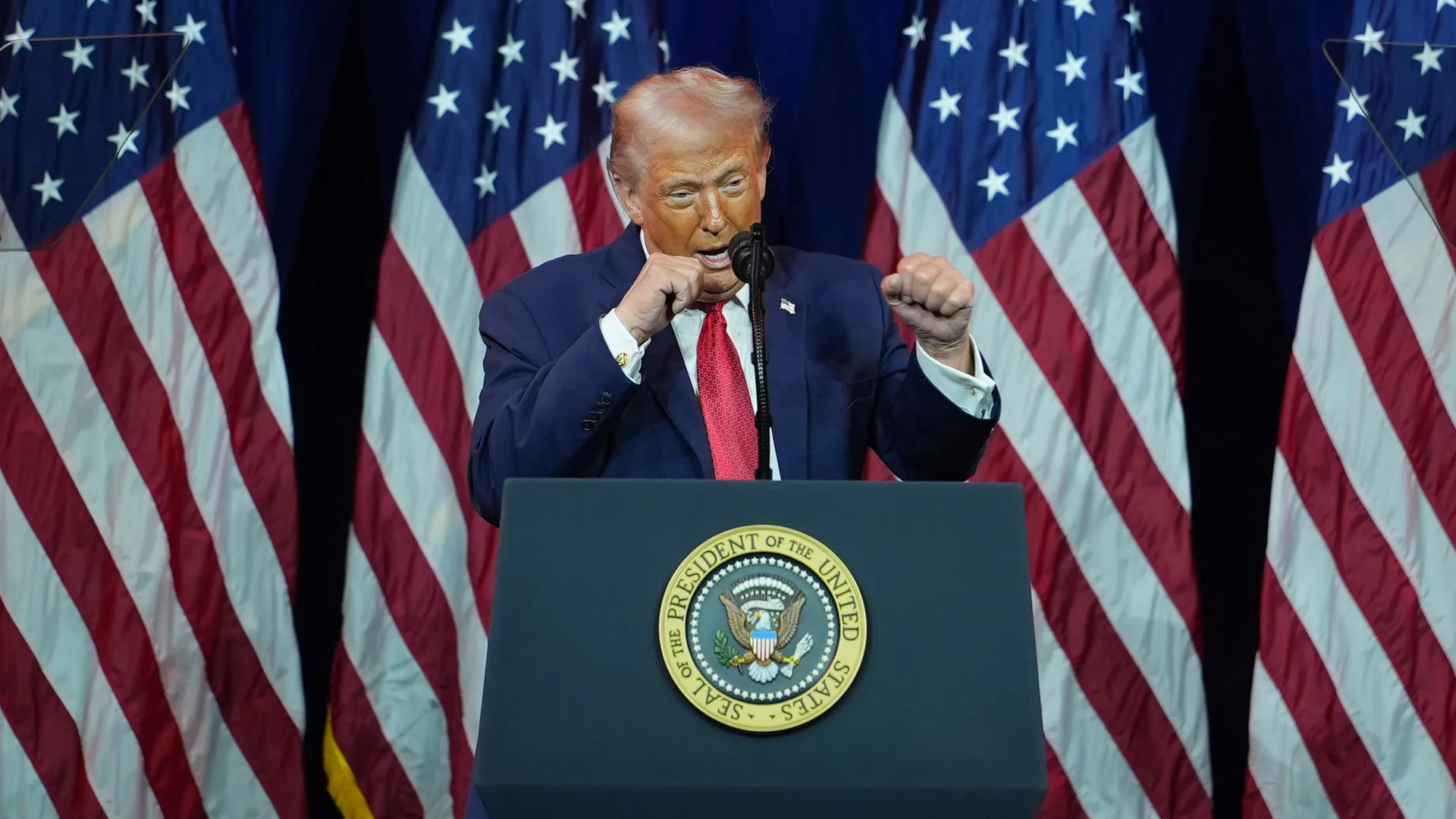

Wrong indeed. Nearly a year into his second term, Trump has done nothing but exacerbate the domestic problems that Greene identified as America First priorities — bringing down the “increasing cost of living, housing, healthcare” within the 50 states — even as he’s pursued the “never ending military aggression” and foreign adventurism that America Firsters scorn, or at least used to. Another Trump con. Another lie.

Here’s a stunning stat, thanks to Military Times: In 2025, Trump ordered 626 missile strikes worldwide, 71 more than President Biden did in his entire four-year term. Targets, so far, have included Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Somalia, Nigeria, Iran and the waters off Venezuela and Colombia. Lately he’s threatened to hit Iran again if it kills demonstrators who have been marching in Tehran’s streets to protest the country’s woeful economic conditions. (“We are locked and loaded and ready to go,” Trump posted Friday.)

The president doesn’t like “forever wars,” he’s said many times, but he sure loves quick booms and cinematic secret ops. Leave aside, for now, the attacks in the Middle East, Africa and the Caribbean and the eastern Pacific. It’s Trump’s new claim to “run” Venezuela that has signaled the beginning of his mind-boggling bid for U.S. hegemony over the Western Hemisphere. Any such ambition raises the potential for quick actions to become quagmires.

As Stephen Miller, perhaps Trump’s closest and most like-minded (read: unhinged) advisor, described the administration’s worldview on Monday to CNN’s Jake Tapper: “We live in a world, in the real world, Jake, that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power. These are iron laws of the world since the beginning of time.”

You know, that old, amoral iron law: “Might makes right.” Music to Vladimir Putin’s and Xi Jinping’s ears as they seek hegemonic expansion of their own, confident that the United States has given up the moral high ground from which to object.

But it was Trump, the branding maven, who gave the White House worldview its name — his own, of course: the Donroe Doctrine. And it was Trump who spelled out what that might mean in practice for the Americas, in a chest-thumping, war-mongering performance on Sunday returning to Washington aboard Air Force One. The wannabe U.S. king turns out to be a wannabe emperor of an entire hemisphere.

“We’re in charge,” Trump said of Venezuela to reporters. “We’re gonna run it. Fix it. We’ll have elections at the right time.” He added, “If they don’t behave, we’ll do a second strike.” He went on, suggestively, ominously: “Colombia is very sick too,” and “Cuba is ready to fall.” Looking northward, he coveted more: “We need Greenland from a national security situation.”

Separately, Trump recently has said that Colombia’s leftist President Gustavo Petro “does have to watch his ass,” and that, given Trump’s unhappiness with the ungenuflecting Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, “Something’s going to have to be done with Mexico.” In their cases as well as Maduro’s, Trump’s ostensible complaints have been that each has been complacent or complicit with drug cartels.

And yet, just last month Trump pardoned the former president of Honduras, Juan Orlando Hernández, who was convicted in a U.S. court and given a 45-year sentence for his central role in “one of the largest and most violent drug-trafficking conspiracies in the world.” Hernández helped traffickers ship 400 tons of cocaine into the United States — to “stuff the drugs up the gringos’ noses.” And Trump pardoned him after less than two years in prison.

So it’s implausible that a few weeks later, the U.S. president truly believes in taking a hard line against leaders he suspects of abetting the drug trade. Maybe Trump’s real motivation is something other than drug-running?

In his appearance after the Maduro arrest, Trump used the word “oil” 21 times. On Tuesday, he announced, in a social media post, of course, that he was taking control of the proceeds from up to 50 barrels of Venezuelan oil. (Not that he cares, but that would violate the Constitution, which gives Congress power to appropriate money that comes into the U.S. Treasury.)

Or perhaps, in line with the Monroe Doctrine, our current president has a retro urge to dominate half the world.

Lately his focus has been on Venezuela and South America, but North America is also in his sights. Trump has long said he might target Mexico to hit cartels and that the United States’ other North American neighbor, Canada, should become the 51st state. But it’s a third part of North America — Greenland — that he’s most intent on.

The icy island has fewer than 60,000 people but mineral wealth that’s increasingly accessible given the climate warming that Trump calls a hoax. For him to lay claim isn’t just a problem for the Americas. It’s an existential threat to NATO given that Greenland is an autonomous part of NATO ally Denmark — as Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen warned.

Not in 80 years did anyone imagine that NATO — bound by its tenet that an attack on one member is an attack on all — would be attacked from within, least of all from the United States. In a remarkable statement on Tuesday, U.S. allies rallied around Denmark: “It is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland.”

Trump’s insistence that controlling Greenland is essential to U.S. national security is nuts. The United States has had military bases there since World War II, and all of NATO sees Greenland as critical to defend against Russian and Chinese encroachment in the Arctic. Still, Trump hasn’t ruled out the use of force to take the island.

He imagines himself to be the emperor of the Americas — all of it. Americas First.

Bluesky: @jackiecalmes

Threads: @jkcalmes

X: @jackiekcalmes