Shipping giant MSC facilitates trade from Israeli settlements through EU | News

Milan, Italy – The world’s largest shipping line has been enabling the transport of goods to and from illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank, as the United States and Europe continue to promote trade despite clear responsibilities under international law, a joint investigation by Al Jazeera and the Palestinian Youth Movement (PYM) reveals.

The Switzerland-based Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) has regularly shipped cargo from companies based in Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territory, according to commercial documents obtained through US import databases.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

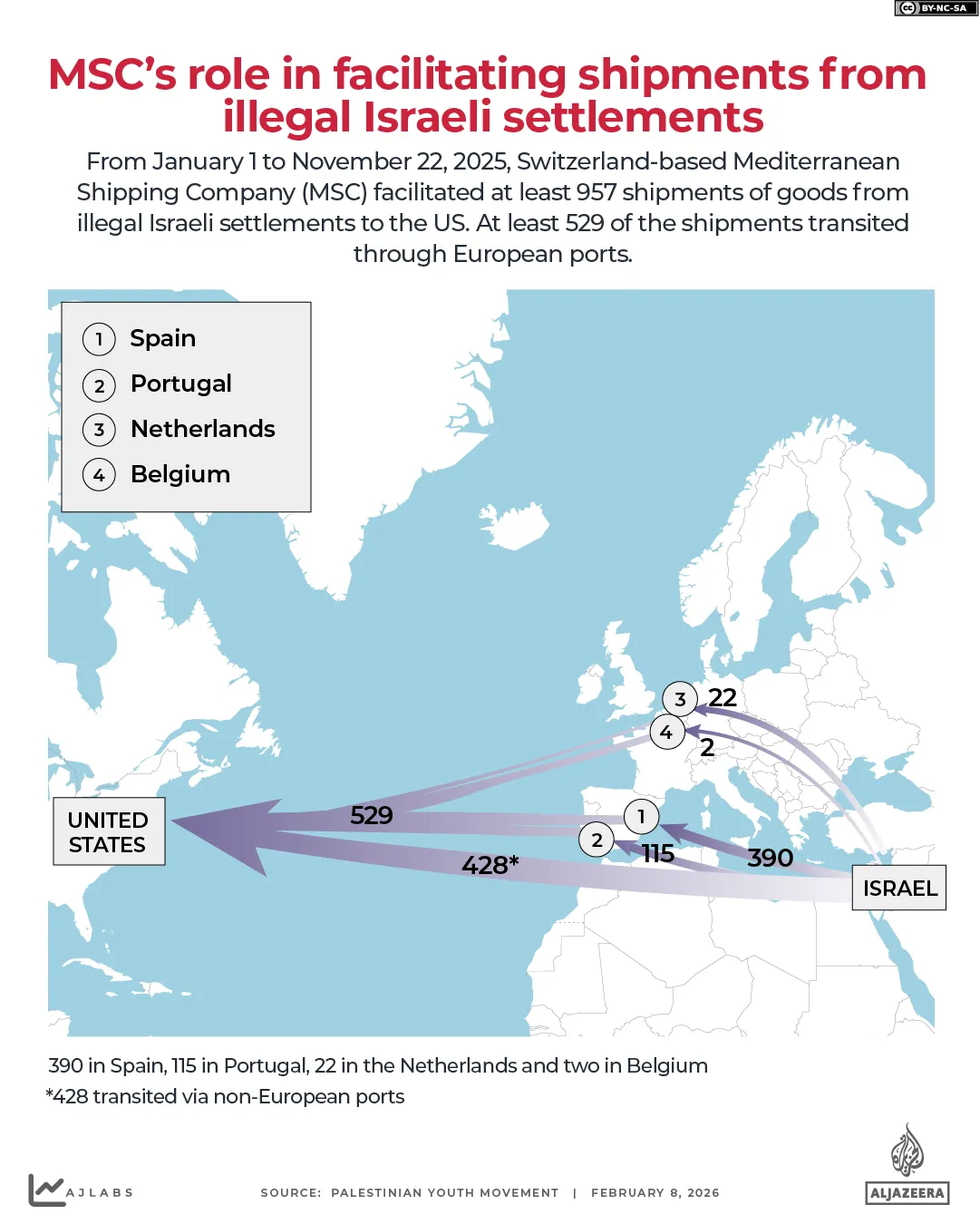

Between January 1 and November 22, 2025, lading bills show that MSC facilitated at least 957 shipments of goods from Israeli outposts to the US. Of these shipments, 529 transited through European ports, including 390 in Spain, 115 in Portugal, 22 in the Netherlands, and two in Belgium.

MSC is privately owned by Italian billionaire Gianluigi Aponte and his wife, Rafaela Aponte-Diamant, who was born in the Israeli city of Haifa in 1945, then under British rule as Mandatory Palestine.

“Israeli settlements are widely considered illegal under international law, because they are built on occupied territory, in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention,” Nicola Perugini, senior lecturer in international relations at the University of Edinburgh, told Al Jazeera. “Commercialising products from these settlements effectively supports the illegal settlements.”

The findings capture a limited portion of the settlement trade, since import and export data from Israel and most European countries is not publicly available. They reveal a reliance on cargo shipping companies and European maritime ports for the transport of a vast range of settlement products, from food items and textiles to skin care and natural stones.

Perugini said states should ban trade with illegal settlements entirely, as it contributes to ongoing violations of international law.

“You cannot normalise the profits of an illegal occupation,” he said.

US, EU positions on illegal settlements

Under President Donald Trump, the US adopted a permissive stance towards Israeli settlements, reversing decades of policy in 2019. Washington declared them as not inherently illegal under international law and continued this approach upon Trump’s re-election in 2025.

While the EU does not recognise Israel’s sovereignty over West Bank settlements and regards them as an “obstacle to peace”, the findings show that goods were delivered directly from European ports to illegal settlements.

In 2025, MSC facilitated at least 14 shipments from Italy, according to Italian export data. In each case, the cargo originated from the port of Ravenna, which stretches along the Adriatic Sea in central Italy, and openly listed the names and zip codes of Israeli settlements as recipients.

The trade stands in contrast with a landmark 2024 opinion by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) advising that third states are obliged to “prevent trade or investment relations that assist in the maintenance of the illegal situation created by Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory”.

The ICJ opinion does not directly address the responsibility of private corporations like MSC.

In April, the UN Human Rights Council urged individual corporate actors to “cease contributing to the establishment, maintenance, development or consolidation of Israeli settlements or the exploitation of the natural resources of the Occupied Palestinian Territory”.

Additionally, a 2024 EU directive on corporate sustainability mandates that large companies working in the bloc identify and address adverse human rights and environmental impacts in their operations.

PYM, a grassroots, international pro-Palestinian movement, last year found that Maersk, Denmark’s publicly owned shipping company, facilitated trade from Israeli settlements.

The world’s biggest container group before being overtaken by MSC in 2022, Maersk is now reviewing its screening process to align with the UN Global Compact, which urges companies to adopt sustainable, socially responsible policies, and guidelines from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to the same effect.

MSC told Al Jazeera in a statement that it “respects global legal frameworks and regulations wherever it operates” and applies this “to all shipments to and from Israel”.

Despite insurance companies raising premiums due to security risk as Israel launched its genocidal war on Gaza in October 2023, MSC announced that it would absorb the extra costs rather than impose war surcharges.

It also holds cooperation and vessel-sharing agreements with Israel’s publicly held cargo shipping company, ZIM.

The Spanish and Italian interior ministries were also contacted by Al Jazeera, but did not respond to requests for comment on the shipments.

The Israeli ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

Sustaining settlement economy

According to UN estimates, settlements in Area C – comprising more than 60 percent of the occupied West Bank that Israel controls – and occupied East Jerusalem contribute about $30bn to the Israeli economy each year.

As Israel enforces administrative and physical barriers that severely limit Palestinian businesses, the West Bank’s economy is understood to have suffered a cumulative loss of $170bn between 2000 and 2024.

Israel has recently accelerated efforts to build illegal settlements in the heart of the occupied West Bank, pressing a controversial project known as E1 that could effectively sever Palestinian land and further cut off East Jerusalem.

The plan includes about 3,500 apartments that would be situated next to the existing settlement of Maale Adumim.

Israel’s far-right finance minister, Bezalel Smotrich, said the project would effectively “bury” the idea of a sovereign Palestinian state.

In August, 21 countries, including Italy and Spain, condemned the plan as a “violation of international law” that risked “undermining security”.

Bills of lading obtained by Al Jazeera and PYM show that MSC delivered shipments on behalf of at least two companies, listing their address in Maale Adumim and the nearby Mishor Adumim industrial zone.

Maya, a wholesale supplier for supplement and candy companies, lists Mishor Adumim in the shipper address in 13 out of 14 shipments. Extal, a private company that develops aluminium solutions and holds partnerships with Israeli weapons manufacturers – including Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) and Rafael Advanced Defense Systems – listed the Mishor Adumim industrial zone in all 38 bills of lading.

Extal is among 158 companies listed by the UN Human Rights Office (OHCHR) in its database of entities officially known to be operating from illegal Israeli settlements.

In at least three other cases, MSC delivered shipments on behalf of settlement-based companies listed in the OHCHR database.

This includes 17 shipments from Ahava Dead Sea Laboratories, an Israeli world-renowned cosmetic brand that has come under intense scrutiny for reportedly pillaging Palestinian natural resources.

A substantial portion of the settlement-based companies listed in the bills of lading were based in the Barkan Industrial Zone, one of the largest in the occupied West Bank. The area was established on confiscated private Palestinian agricultural land and, over the past 20 years, its expansion has led to the fragmentation and isolation of nearby Palestinian villages.

Obligation to uphold human rights

European member states are aware of a gap between the business-as-usual reality on the ground and the mandates of international law.

In June, nine EU countries called on the European Commission to come up with proposals on how to discontinue EU trade with Israeli settlements.

“This is about ensuring that EU policies do not contribute, directly or indirectly, to the perpetuation of an illegal situation,” the letter addressed to EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas said. It was signed by foreign ministers from Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.

The European Commission has not fulfilled the request. Currently, products originating from the settlements can be imported into Europe, but do not benefit from the preferential tariffs of the EU-Israel Association Agreement. Since an EU court ruling in 2019, they must be labelled as originating from Israeli settlements.

Hugh Lovatt, senior policy fellow with the Middle East and North Africa programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), said the EU theoretically has an obligation to align its policies with international law.

Whether that happens “comes down to a political decision”.

“Human rights abuses should be a core criterion for deciding what to buy and what to invest in,” he said. “But in the current global attitude, that approach has been increasingly undermined.”

In 2022, restrictions on trade and investment were imposed on Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine following Moscow’s full-scale invasion, but no similar measures were taken towards illegal Israeli settlements.

A few member states have opted to take independent action. Spain and Slovenia last year banned the imports of goods produced in Israeli settlements, while Ireland, Belgium and the Netherlands are working on legislation.

As of January 2026, Spain banned importing goods produced in Israeli settlements, but its measures do not make explicit mention of transshipments through its ports.

Bills of lading obtained as part of this investigation show that the port of Valencia plays a key role, receiving 358 out of a total of 390 shipments transiting through Spain.

Several bills of lading directly reference illegal settlements in the Syrian Golan Heights.

Aquestia Ltd, a company that specialises in hydraulic systems, list Kfar Haruv and Ramat HaGolan in the shipper address. Miriam Shoham, which exports fresh fruit, also lists Ramot HaGolan, while polypropylene manufacturer Mapal Cooperative Society lists Mevo Hama.

PYM said, “MSC’s transfers to and from Israeli settlements are systemic and in violation of both international and domestic Spanish laws.

“MSC provides the infrastructure connecting illegal settlements to global markets, thus encouraging further occupation of Palestinian and Syrian land.”