Newsom’s fight with Trump and RFK Jr. on public health

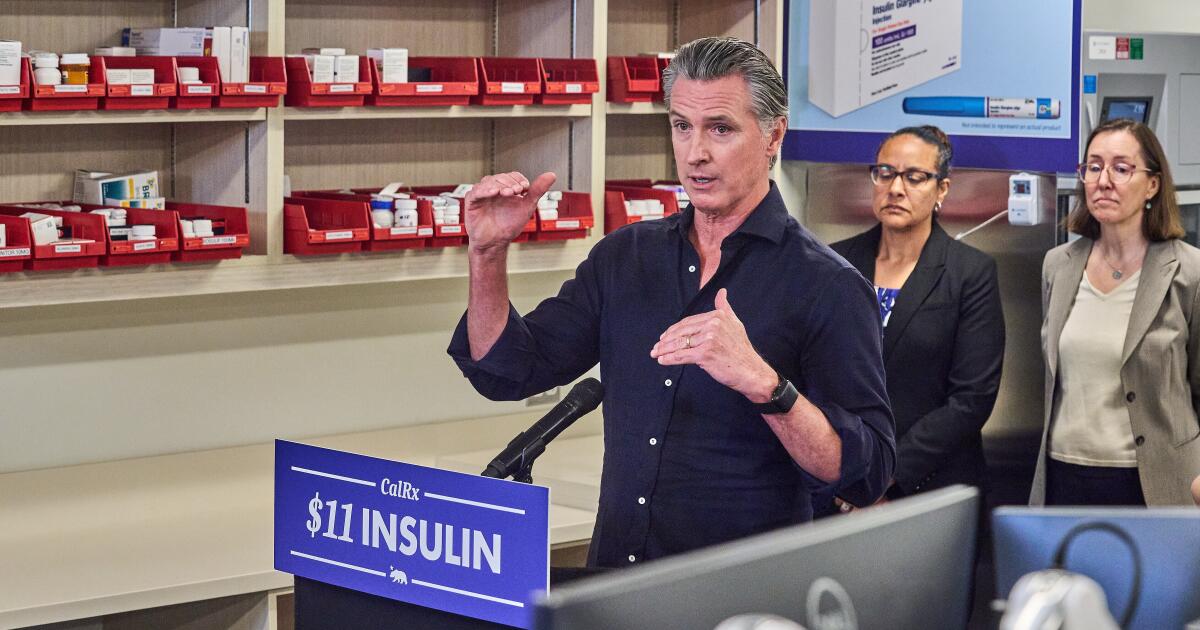

SACRAMENTO — California Gov. Gavin Newsom has positioned himself as a national public health leader by staking out science-backed policies in contrast with the Trump administration.

After Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. fired Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Susan Monarez for refusing what her lawyers called “the dangerous politicization of science,” Newsom hired her to help modernize California’s public health system. He also gave a job to Debra Houry, the agency’s former chief science and medical officer, who had resigned in protest hours after Monarez’s firing.

Newsom also teamed up with fellow Democratic governors Tina Kotek of Oregon, Bob Ferguson of Washington and Josh Green of Hawaii to form the West Coast Health Alliance, a regional public health agency, whose guidance the governors said would “uphold scientific integrity in public health as Trump destroys” the CDC’s credibility. Newsom argued establishing the independent alliance was vital as Kennedy leads the Trump administration’s rollback of national vaccine recommendations.

More recently, California became the first state to join a global outbreak response network coordinated by the World Health Organization, followed by Illinois and New York. Colorado and Wisconsin signaled they plan to join. They did so after President Trump officially withdrew the United States from the agency on the grounds that it had “strayed from its core mission and has acted contrary to the U.S. interests in protecting the U.S. public on multiple occasions.” Newsom said joining the WHO-led consortium would enable California to respond faster to communicable disease outbreaks and other public health threats.

Although other Democratic governors and public health leaders have openly criticized the federal government, few have been as outspoken as Newsom, who is considering a run for president in 2028 and is in his second and final term as governor. Members of the scientific community have praised his effort to build a public health bulwark against the Trump administration’s slashing of funding and scaling back of vaccine recommendations.

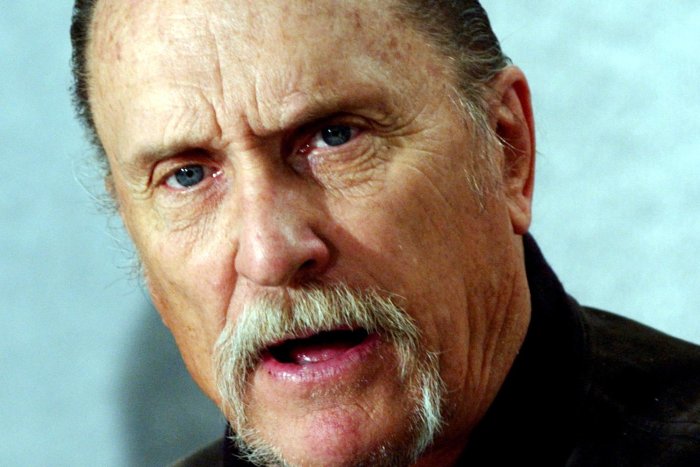

What Newsom is doing “is a great idea,” said Paul Offit, an outspoken critic of Kennedy and a vaccine expert who formerly served on the Food and Drug Administration’s vaccine advisory committee but was removed under Trump in 2025.

“Public health has been turned on its head,” Offit said. “We have an anti-vaccine activist and science denialist as the head of U.S. Health and Human Services. It’s dangerous.”

The White House did not respond to questions about Newsom’s stance and Health and Human Services declined requests to interview Kennedy. Instead, federal health officials criticized Democrats broadly, arguing that blue states are participating in fraud and mismanagement of federal funds in public health programs.

Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said the administration is going after “Democrat-run states that pushed unscientific lockdowns, toddler mask mandates, and draconian vaccine passports during the COVID era.” She said those moves have “completely eroded the American people’s trust in public health agencies.”

Public health guided by science

Since Trump returned to office, Newsom has criticized the president and his administration for engineering policies that he sees as an affront to public health and safety, labeling federal leaders as “extremists” trying to “weaponize the CDC and spread misinformation.” He has excoriated federal officials for erroneously linking vaccines to autism, warning that the administration is endangering the lives of infants and young children in scaling back childhood vaccine recommendations. And he argued that the White House is unleashing “chaos” on America’s public health system in backing out of the WHO.

The governor declined an interview request, but Newsom spokesperson Marissa Saldivar said it’s a priority of the governor “to protect public health and provide communities with guidance rooted in science and evidence, not politics and conspiracies.”

The Trump administration’s moves have triggered financial uncertainty that local officials said has reduced morale within public health departments and left states unprepared for disease outbreaks and prevention efforts. The White House last year proposed cutting Health and Human Services spending by $33 billion, including $3.6 billion from the CDC. Congress largely rejected those cuts last month, although funding for programs focusing on social drivers of health, such as access to food, housing and education, were axed.

The Trump administration announced that it would claw back more than $600 million in public health funds from California, Colorado, Illinois and Minnesota, arguing that the Democratic-led states were funding “woke” initiatives that didn’t reflect White House priorities. Within days, the states sued and a judge temporarily blocked the cut.

“They keep suddenly canceling grants and then it gets overturned in court,” said Kat DeBurgh, executive director of the Health Officers Assn. of California. “A lot of the damage is already done because counties already stopped doing the work.”

Federal funding has accounted for more than half of state and local health department budgets nationwide, with money going toward fighting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, preventing chronic diseases, and boosting public health preparedness and communicable disease response, according to a 2025 analysis by KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

Federal funds account for $2.4 billion of California’s $5.3-billion public health budget, making it difficult for Newsom and state lawmakers to backfill potential cuts. That money helps fund state operations and is vital for local health departments.

Funding cuts hurt all

Los Angeles County public health director Barbara Ferrer said if the federal government is allowed to cut that $600 million, the county of nearly 10 million residents would lose an estimated $84 million over the next two years, in addition to other grants for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Ferrer said the county depends on nearly $1 billion in federal funding annually to track and prevent communicable diseases and combat chronic health conditions, including diabetes and high blood pressure. Already, the county has announced the closure of seven public health clinics that provided vaccinations and disease testing, largely because of funding losses tied to federal grant cuts.

“It’s an ill-informed strategy,” Ferrer said. “Public health doesn’t care whether your political affiliation is Republican or Democrat. It doesn’t care about your immigration status or sexual orientation. Public health has to be available for everyone.”

A single case of measles requires public health workers to track down 200 potential contacts, Ferrer said.

The U.S. eliminated measles in 2000 but is close to losing that status as a result of vaccine skepticism and misinformation spread by vaccine critics. The U.S. had 2,281 confirmed cases last year, the most since 1991, with 93% in people who were unvaccinated or whose vaccination status was unknown. This year, the highly contagious disease has been reported at schools, airports and Disneyland.

Public health officials hope the West Coast Health Alliance can help counteract Trump by building trust through evidence-based public health guidance.

“What we’re seeing from the federal government is partisan politics at its worst and retaliation for policy differences, and it puts at extraordinary risk the health and well-being of the American people,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Assn., a coalition of public health professionals.

Robust vaccine schedule

Erica Pan, California’s top public health officer and director of the state Department of Public Health, said the West Coast Health Alliance is defending science by recommending a more robust vaccine schedule than the federal government. California is part of a coalition suing the Trump administration over its decision to rescind recommendations for seven childhood vaccines, including for hepatitis A, hepatitis B, influenza and COVID-19.

Pan expressed deep concern about the state of public health, particularly the uptick in measles. “We’re sliding backwards,” Pan said of immunizations.

Sarah Kemble, Hawaii’s state epidemiologist, said Hawaii joined the alliance after hearing from pro-vaccine residents who wanted assurance that they would have access to vaccines.

“We were getting a lot of questions and anxiety from people who did understand science-based recommendations but were wondering, ‘Am I still going to be able to go get my shot?’” Kemble said.

Other states led mostly by Democrats have also formed alliances, with Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and several other East Coast states banding together to create the Northeast Public Health Collaborative.

Hilliard, of Health and Human Services, said that even as Democratic governors establish vaccine advisory coalitions, the federal Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices “remains the scientific body guiding immunization recommendations in this country, and HHS will ensure policy is based on rigorous evidence and gold standard science, not the failed politics of the pandemic.”

Influencing red states

Newsom, for his part, has approved a recurring annual infusion of nearly $300 million to support the state Department of Public Health, as well as the 61 local public health agencies across California, and last year signed a bill authorizing the state to issue its own immunization guidance. It requires health insurers in California to provide patient coverage for vaccinations the state recommends even if the federal government doesn’t.

Jeffrey Singer, a doctor and senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute, said decentralization can be beneficial. That’s because local media campaigns that reflect different political ideologies and community priorities may have a better chance of influencing the public.

A KFF analysis found some red states are joining blue states in decoupling their vaccine recommendations from the federal government’s. Singer said some doctors in his home state of Arizona are looking to more liberal California for vaccine recommendations.

“Science is never settled, and there are a lot of areas of this country where there are differences of opinion,” Singer said. “This can help us challenge our assumptions and learn.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.