Somalia is the missing pillar of Red Sea and Gulf of Aden stability | Opinions

Global markets rarely reveal their vulnerabilities quietly. They do so when shipping lanes come under threat, energy prices surge, or supply chains fracture. Few regions illustrate this reality more starkly than the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, which are now among the world’s most contested maritime corridors. What unfolds along these waters no longer remains local. It shapes economic security across the Arab world and far beyond.

Yet, amid growing attention to this strategic corridor, one factor remains persistently underestimated: Somalia.

For decades, Somalia was viewed primarily through the lens of conflict and fragility. That narrative no longer reflects today’s reality. The country is undergoing a consequential transition, moving away from prolonged instability, rebuilding state institutions, and re-emerging as a sovereign actor with growing regional relevance. Situated at the intersection of the Arab world, Africa, the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Aden, Somalia is not peripheral to regional stability; it is central to it.

Geography alone explains much of this significance. With the longest coastline in mainland Africa, Somalia lies adjacent to the Bab al-Mandeb passage connecting the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and the wider Indian Ocean. A substantial share of global maritime trade and energy shipments passes through this corridor. Disruptions along Somalia’s coast, therefore, have immediate implications for shipping reliability, energy markets, and food security — issues of direct concern to Gulf states and Arab economies.

For the Arab world, Somalia should be understood not as distant terrain but as a front-line partner in regional security. Stability along Somalia’s coastline helps contain threats before they reach the Arabian Peninsula, whether in the form of violent extremism, illicit trafficking networks, piracy, or the entrenchment of hostile external military presences along Africa’s eastern flank.

Somalia is not attempting to build stability from scratch. Despite persistent challenges, tangible progress has been made. Federal governance structures are functioning. National security forces are undergoing professionalisation. Public financial management has improved. Diplomatically, Somalia has reasserted itself within the Arab League, the African Union, and multilateral forums. These gains continue to be built on daily and reflect a clear commitment to sovereign statehood, territorial unity, and partnership rather than dependency. Somalia today seeks strategic alignment grounded in mutual interest, not charity.

Somalia’s relevance also extends beyond security. Its membership in the East African Community integrates the country into one of the world’s fastest-growing population and consumer regions. East Africa’s rapid demographic expansion, urbanisation, and economic integration position Somalia as a natural bridge between Gulf capital and African growth markets.

There is a clear opportunity for Somalia to emerge as a logistics and transshipment gateway linking the Gulf, the Red Sea, East Africa and the Indian Ocean. With targeted investments in ports, transport corridors, and maritime security, Somalia can become a critical node in regional supply chains supporting trade diversification, food security, and economic resilience across the Arab world.

At the heart of Somalia’s potential is its dynamic population. More than 70 percent of Somalis are aged below 30. This generation is increasingly urban, digitally connected, and entrepreneurial. Somali traders and business networks already operate across Southern and Eastern Africa, spanning logistics, finance, retail, and services. A large and dynamic diaspora across the Gulf, Europe, North America, and Africa further amplifies this reach through remittances, investment, and transnational expertise.

None of these momentums, however, can be sustained without security. A capable, nationally legitimate Somali security sector is the foundation for durable stability, investment confidence, and regional integration.

For Gulf states and the wider Arab world, supporting Somalia’s security sector is therefore not an act of altruism. It is a strategic investment in a reliable stabilising partner. Effective Somali security institutions contribute directly to safeguarding Red Sea and Gulf of Aden maritime corridors, countering transnational terrorism before it reaches Arab shores, protecting emerging logistics infrastructure, and denying external actors opportunities to exploit governance vacuums. Such support must prioritise institution-building, Somali ownership, and long-term sustainability, not short-term fixes or proxy competition.

The stakes are rising. The Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden are entering a period of heightened strategic contestation. Fragmentation along their African coastline poses a direct risk to Arab collective security. Recent developments underscore this urgency.

Israel’s unilateral recognition of the northern Somali region of Somaliland, pursued outside international legal frameworks and without Somali consent, is widely viewed as an attempt to secure a military foothold along these strategic waters, risking the introduction of the Arab-Israeli conflict into the Gulf’s security environment.

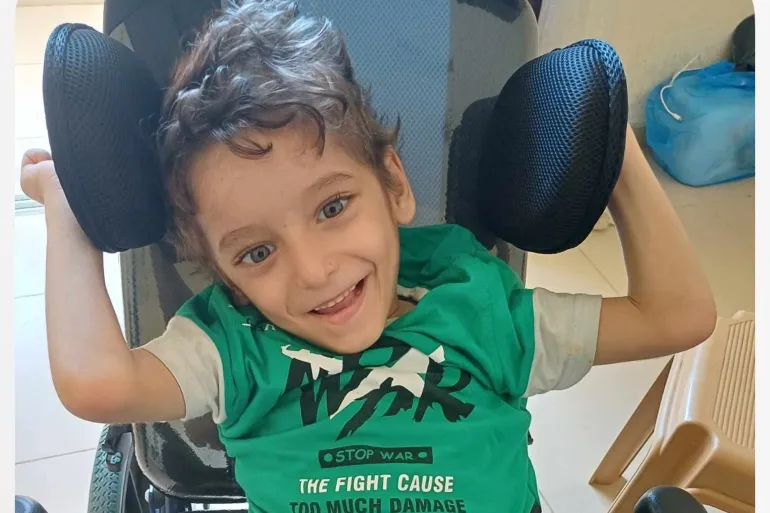

Even more troubling are emerging narratives advocating the forced displacement of Palestinians from Gaza, with proposals to relocate them to Somaliland against their will. Such ideas, whether formally advanced or not, represent grave violations of international law and human dignity. Exporting the consequences of occupation and war onto African soil would not resolve conflict; it would multiply it.

For the Arab world, this should serve as a wake-up call. Allowing external actors to fragment sovereign states or instrumentalise fragile regions for unresolved conflicts carries long-term consequences. Somalia’s unity and stability, therefore, align squarely with core Arab strategic interests and with longstanding Arab positions on sovereignty, justice and self-determination.

Somalia is ready to be part of the solution. With calibrated strategic support, particularly in security sector development and logistics infrastructure, Somalia can emerge as a cornerstone of Red Sea and Gulf of Aden stability, a gateway to East Africa, and a long-term partner for the Arab world.

The question is no longer whether Somalia matters in the regional and global Red Sea and Gulf of Aden discussions and plans. It is whether the region will act on that reality before others do.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.