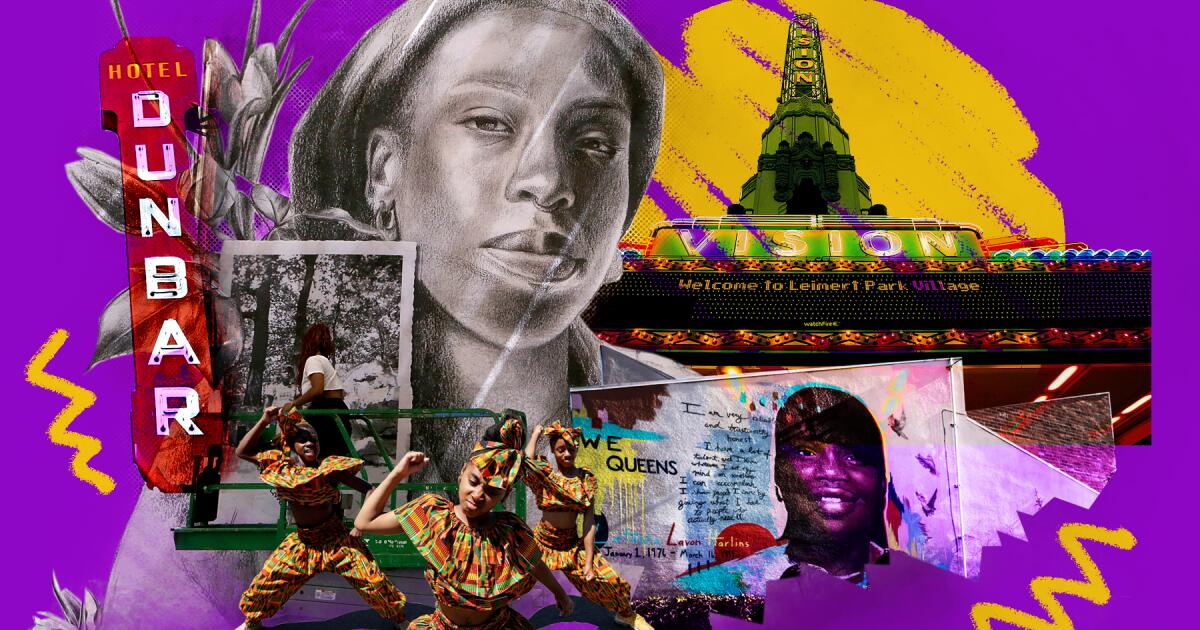

A guide to Studio City: Best things to do, see and eat

The San Fernando Valley is back in the spotlight, thanks in part to Bravo’s reality franchise “The Valley,” where viewers may recognize a slew of Ventura Boulevard staples (we see you, Rocco’s Tavern).

Much of the show is filmed in and around Studio City, a neighborhood just west of the Cahuenga Pass, about 10 miles from downtown L.A. and within the city of Los Angeles.

That last fact is what usually throws people off guard.

“Isn’t Studio City a separate city from L.A.?” they ask.

This is when I must reply no and launch into an explanation on the expansiveness of the 818, the identity crisis it never asked for and how its lore has endured for decades on the silver screen, from “Fast Times at Ridgemont High” to “The Karate Kid” and “Licorice Pizza,” to name a few.

See, long before Kendall Jenner bottled our area code with her tequila brand or “The Valley’s” Golnesa “GG” Gharachedaghi created her Valley Girl jewelry line (a response to a castmate’s constant gripe that the area had no vibe), Studio City was already a vibrant L.A. hub. It claimed a roster of power players — “The Brady Bunch” soundstage, Laurel Canyon News and the iconic Studio City Hand Car Wash — all of which still transcend ratings or storyline.

The neighborhood was originally formed around film producer Mack Sennett’s studio, which later became Republic Studios and then CBS Studio Center. With the studio as the focal point, the U.S. Postal Service designated its branch in that area as the Studio City Post Office, formalizing the name Studio City. Not exactly poetic, but it stuck. By the 1940s, Studio City developed into a “just over the hill” refuge for Hollywood’s working families, with new restaurants and bars abuzz.

My first memories of Studio City were hanging out with a childhood friend whose parents worked at CBS, and back then, it felt like the ultimate suburban dream. Fast forward to the mid-aughts and I got to live it myself, renting an apartment a few blocks from Tujunga Village, the neighborhood’s own “small-town U.S.A.” I spent countless weekends perusing food stands and trendy coffeehouses, the flaky bread and baked goods reviving me after hours of line dancing at Oil Can Harry’s or a booze-soaked late night at Page 71.

As one of the Valley’s most social enclaves, where nature is within reach, strip mall sushi is world-class and shaded residential streets feel worlds away from the Sunset Strip, Studio City still feels like the perfect remedy. Sure, finding parking after 6 p.m. can feel like something out of “The Hunger Games,” but on any given weekend you’ll still find me channeling my inner Katniss, circling blocks and deciphering cryptic signage all to revisit one of the L.A. neighborhoods that raised me.

Studio City must be the place. Then again, it always was.

What’s included in this guide

Anyone who’s lived in a major metropolis can tell you that neighborhoods are a tricky thing. They’re eternally malleable and evoke sociological questions around how we place our homes, our neighbors and our communities within a wider tapestry. In the name of neighborly generosity, we may include gems that linger outside of technical parameters. Instead of leaning into stark definitions, we hope to celebrate all of the places that make us love where we live.

Our journalists independently visited every spot recommended in this guide. We do not accept free meals or experiences. What L.A. neighborhood should we check out next? Send ideas to guides@latimes.com.