Some of the biggest names behind the artificial intelligence boom are looking to stack Congress with allies who support lighter regulation of the emerging technology by drawing on the crypto industry’s 2024 election success.

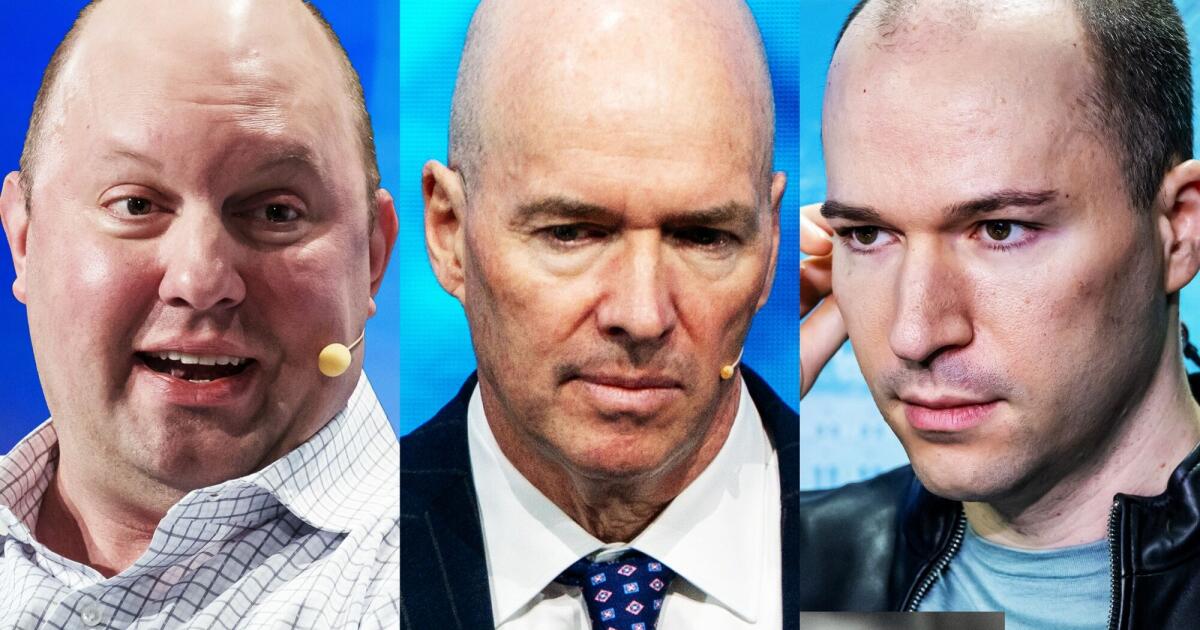

Marc Andreessen, Ben Horowitz and OpenAI co-founder Greg Brockman are among tech leaders who’ve poured $50 million into a new super political action committee to help AI-friendly candidates prevail in November’s congressional races. Known as Leading the Future, the super PAC has taken center stage as voters grow increasingly concerned that AI risks driving up energy costs and taking away jobs.

As it launches operations, Leading the Future is deploying a strategy that worked two years ago for crypto advocates: talk about what’s likely to resonate with voters, not the industry or its interests and controversies. For AI, that means its ads won’t tout the technology but instead discuss core issues including economic opportunity and immigration — even if that means not mentioning AI at all.

“They’re trying to be helpful in a campaign rather than talking about their own issue all the time,” said Craig Murphy, a Republican political consultant in Texas, where Leading the Future has backed Chris Gober, an ally of President Trump, in the state’s hotly contested 10th congressional district.

This year, the group plans to spend up to $125 million on candidates who favor a single, national approach to AI regulation, regardless of party affiliation. The election comes at a crucial moment for the industry as it invests hundreds of billions of dollars in AI infrastructure that will put fresh strains on resources, with new data centers already blamed for driving up utility bills.

Leading the Future faces a growing challenge from AI safety advocates, who’ve started their own super PAC called Public First with a goal of raising $50 million for candidates who favor stricter oversight. On Thursday, Public First landed a $20-million pledge from Anthropic PBC, a rival to OpenAI that has set itself apart from other AI companies by supporting tougher rules.

Polls show deepening public concern over AI’s impact on everything from jobs to education to the environment. Sixty-two percent of US adults say they interact with AI at least several times a week, and 58% are concerned the government will not go far enough in regulating it, according to the Pew Research Center.

Jesse Hunt, a Leading the Future spokesman, said the group is “committed to supporting policymakers who want a smart national regulatory framework for AI,” one that boosts US employment while winning the race against China. Hunt said the super PAC backs ways to protect consumers “without ceding America’s technological future to extreme ideological gatekeepers.”

The political and economic stakes are enormous for OpenAI and others behind Leading the Future, including venture capitalists Andreessen and Horowitz. Their firm, a16z, is the richest in Silicon Valley with billions of dollars invested in AI upstarts including coding startup Cursor and AI leaderboard platform LM Arena.

For now, their super PAC is doing most of the talking for the AI industry in the midterm races. Meta Platforms Inc. has announced plans for AI-related political spending on state-level contests, with $20 million for its California-based super PAC and $45 million for its American Technology Excellence Project, according to Politico.

Other companies with massive AI investment plans — Amazon.com Inc., Alphabet Inc. and Microsoft Corp. — have their own corporate PACs to dole out bipartisan federal campaign donations. Nvidia Corp., the chip giant driving AI policy in Washington, doesn’t have its own PAC.

Bipartisan push

To ensure consistent messaging across party lines, Leading the Future has created two affiliated super PACs — one spending on Republicans and another on Democrats. The aim is to build a bipartisan coalition that can be effective in Washington regardless of which party is in power.

Texas, home of OpenAI’s massive Stargate project, is one of the states where Leading the Future has already jumped in. Its Republican arm, American Mission, has spent nearly $750,000 on ads touting Gober, a political lawyer who’s previously worked for Elon Musk’s super PAC and is in a crowded GOP primary field for an open House seat.

The ads hail Gober as a “MAGA warrior” who “will fight for Texas families, lowering everyday costs.” Gober’s campaign website lists “ensuring America’s AI dominance” as one of his top campaign priorities. Gober’s campaign didn’t respond to requests for comment.

In New York, Leading the Future’s Democratic arm, Think Big, has spent $1.1 million on television ads and messages attacking Alex Bores, a New York state assemblyman who has called for tougher AI safety protocols and is now running for an open congressional seat encompassing much of central Manhattan.

The ads seize on Democrats’ revulsion over Trump’s immigration crackdown and target Bores for his work at Palantir Technologies Inc., which contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Think Big has circulated mailings and text messages citing Bores’ work with Palantir, urging voters to “Reject Bores’ hypocrisy on ICE.”

In an interview, Bores called the claims in the ads false, explaining that he left Palantir because of its work with ICE. He pointed out the irony that Joe Lonsdale, a Palantir co-founder who’s backed the administration’s border crackdown, is a donor to Leading the Future.

“They’re not being ideologically consistent,” Bores said. “The fact that they have been so transparent and said, ‘Hey, we’re the AI industry and Alex Bores will regulate AI and that scares us,’ has been nothing but a benefit so far.”

Leading the Future’s Democratic arm also plans to spend seven figures to support Democrats in two Illinois congressional races: former Illinois Representatives Jesse Jackson Jr. and Melissa Bean.

Following crypto’s path

Leading the Future is following the path carved by Fairshake, a pro-cryptocurrency super PAC that joined affiliates in putting $133 million into congressional races in 2024. Fairshake made an early mark by spending $10 million to attack progressive Katie Porter in the California Democratic Senate primary, helping knock her out of the race in favor of Adam Schiff, the eventual winner who’s seen as more friendly to digital currency.

The group also backed successful primary challengers against House incumbents, including Democrats Cori Bush in Missouri and Jamaal Bowman in New York. Both were rated among the harshest critics of digital assets by the Stand With Crypto Alliance, an industry group.

In its highest-profile 2024 win, Fairshake spent $40 million to help Republican Bernie Moreno defeat incumbent Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown, a crypto skeptic who led the Senate Banking Committee. Overall, it backed winners in 52 of the 61 races where it spent at least $100,000, including victories in three Senate and nine House battlegrounds.

Fairshake and Leading the Future share more than a strategy. Josh Vlasto, one of Leading the Future’s political strategists, does communications work for Fairshake. Andreessen and Horowitz are also among Fairshake’s biggest donors, combining to give $23.8 million last year.

But Leading the Future occasionally conflicts with Fairshake’s past spending. The AI group said Wednesday it plans to spend half a million dollars on an ad campaign for Laurie Buckhout, a former Pentagon official who’s seeking a congressional seat in North Carolina with calls to slash rules “strangling American innovation.” In 2024, during Buckhout’s unsuccessful run for the post, Fairshake spent $2.3 million supporting her opponent and eventual winner, Democratic Rep. Donald Davis.

Regulation proponents

“The fact that they tried to replay the crypto battle means that we have to engage,” said Brad Carson, a former Democratic congressman from Texas who helped launch Public First. “I’d say Leading the Future was the forcing function.”

Unlike crypto, proponents of stricter AI regulations have backers within the industry. Even before its contribution to Public First, Anthropic had pressed for “responsible AI” with sturdier regulations for the fast-moving technology and opposed efforts to preempt state laws.

Anthropic employees have also contributed to candidates targeted by Leading the Future, including a total of $168,500 for Bores, Federal Election Commission records show. A super PAC Dream NYC, whose only donor in 2025 was an Anthropic machine learning researcher who gave $50,000, is backing Bores as well.

Carson, who’s co-leading the super PAC with former Republican Rep. Chris Stewart of Utah, cites public polling that more than 80% of US adults believe the government should maintain rules for AI safety and data security, and says voter sentiment is on Public First’s side.

Public First didn’t disclose receiving any donations last year, according to FEC filings. But one of the group’s affiliated super PACs, Defend our Values PAC, reported receiving $50,000 from Public First Action Inc., the group’s advocacy arm. The PAC hasn’t yet spent any of that money on candidates.

Crypto’s clout looms large in lawmakers’ memory, casting a shadow over any effort to regulate the big tech companies, said Doug Calidas, head of government affairs for AI safety group Americans for Responsible Innovation.

“Fairshake was just so effective,” said Calidas, whose group has called for tougher AI regulations. “Democrats and Republicans are scared they’re going to replicate that model.”

Allison and Birnbaum write for Bloomberg.