Latin America’s political landscape has seen sweeping shifts in recent years. On one hand, a so-called “second Pink Tide” has returned left-of-centre governments to power in key countries – Lula in Brazil, Petro in Colombia, and the broad left in Mexico – inspiring hopes of renewed democracy and social reform. On the other hand, strongman leaders like El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele (a populist outsider not usually labelled “leftist”) and Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro (an entrenched Chavista) have consolidated control in ways critics call authoritarian. The question looms: are these developments evidence that the region is sliding back toward autocracy, cloaked in progressive rhetoric? Or are they legitimate shifts reflecting popular will and necessary reform? Recent trends in Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, El Salvador, and Venezuela, show serious democratic backsliding, populist leadership styles, and the uses (and abuses) of leftist language to consolidate power rather than give it back to the people.

Brazil: Lula’s Left Turn and the Security State

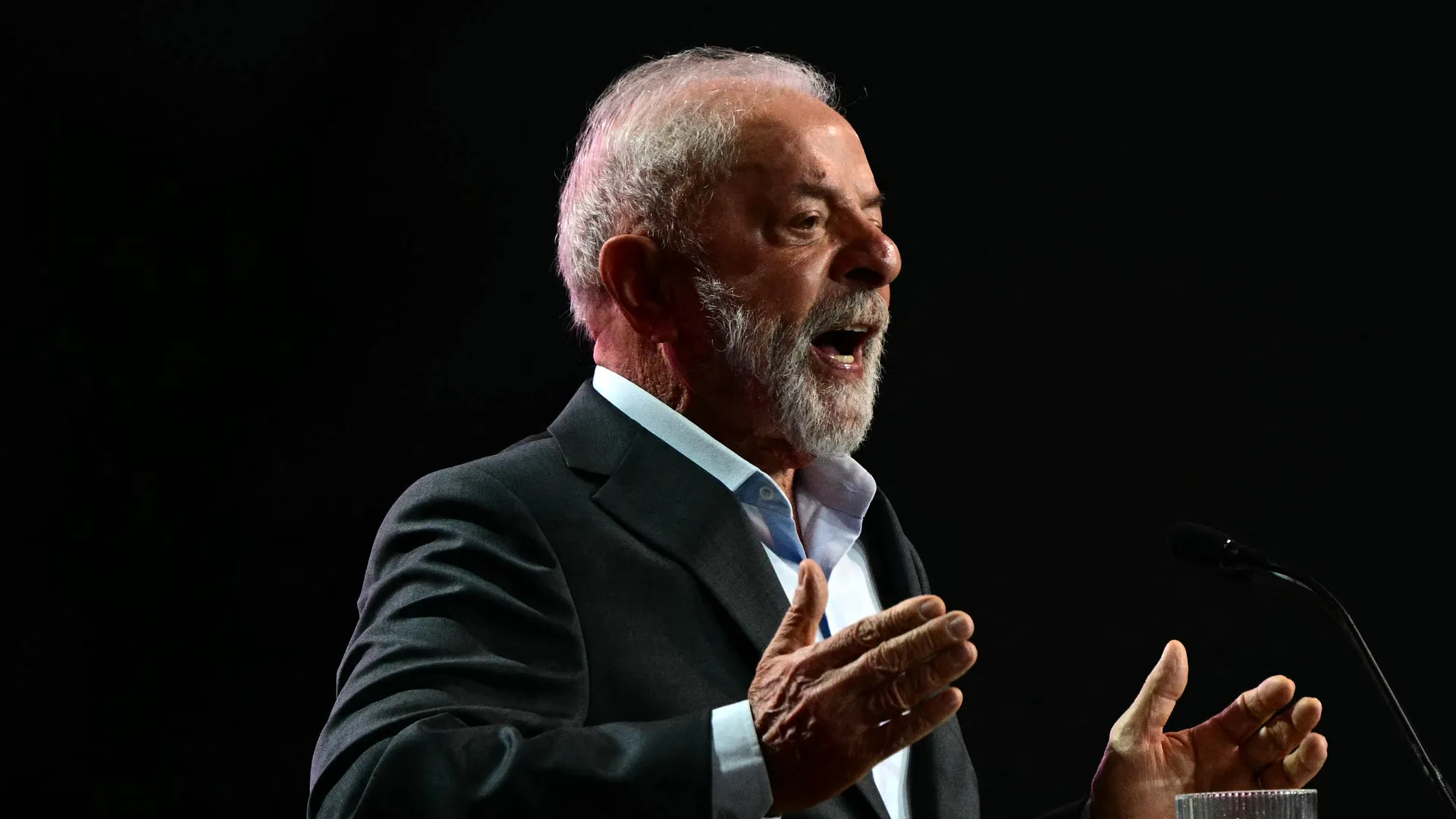

Brazil’s democracy was violently tested in early 2023 when Jair Bolsonaro’s supporters stormed Congress, the Supreme Court, and the presidential palace. The crisis – and the swift legal response by institutions – helped vindicate Brazil’s checks and balances. When former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) won the 2022 election, many Brazilians breathed a sigh of relief as they felt and agreed that a second Bolsonaro term would have propelled Brazil further into autocracy, whereas Lula’s coalition blocked that outcome. Polls showed Brazilians rallying to defend democracy after the Jan. 8 insurrection, and Lula himself has repeatedly proclaimed Brazil a “champion of democracy” on the world stage. Under Lula, Brazil has indeed reversed some of Bolsonaro’s more extreme policies, especially on the environment and social welfare, and the Supreme Court remains independent and active.

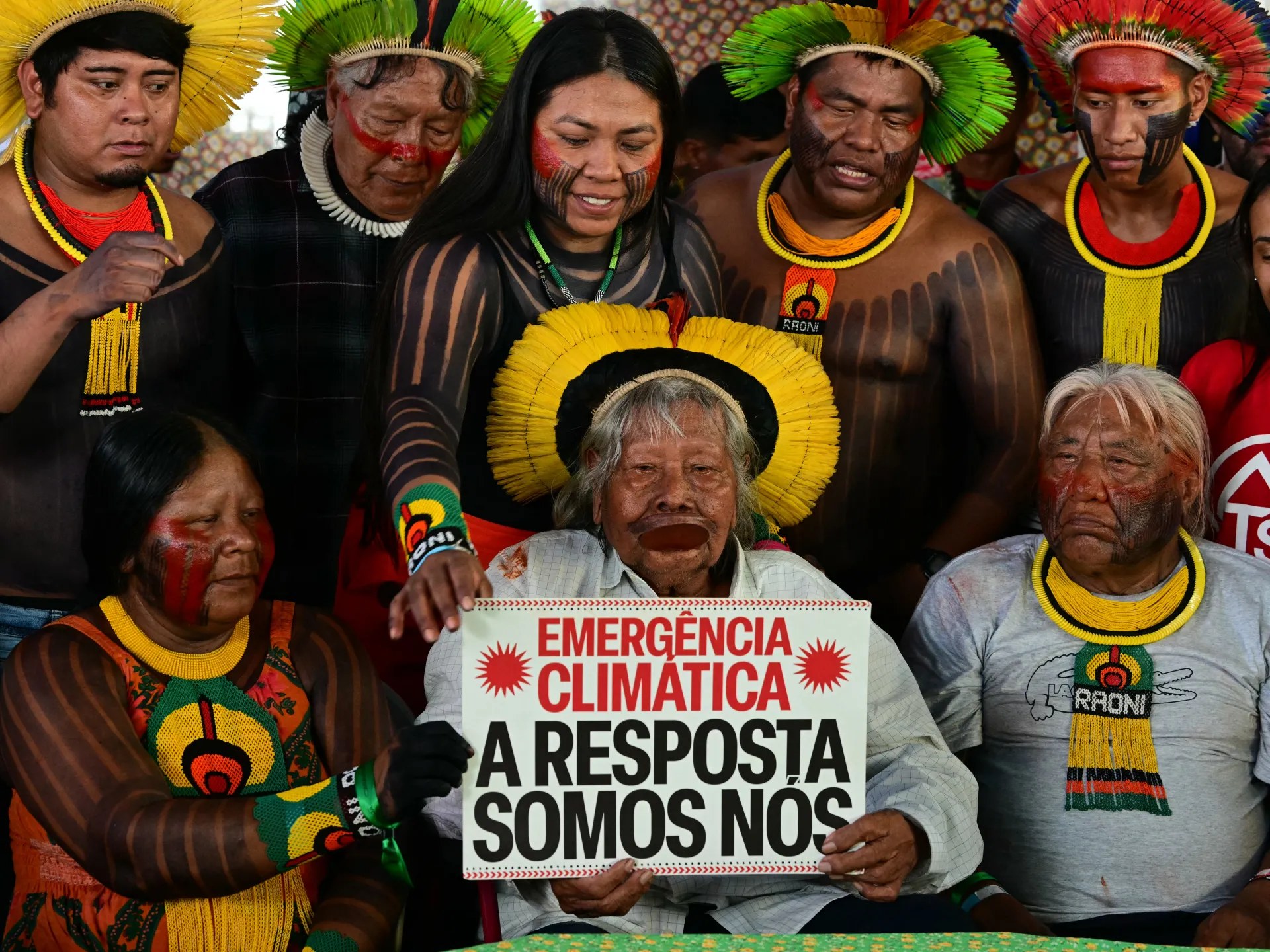

At the same time, Brazil still grapples with brutal crime and controversial security policies. In October 2025 a massive police raid in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas – involving roughly 2,500 officers – killed at least 119 people (115 suspected traffickers and 4 officers). Human rights groups denounced the operation as a massacre, reporting that many of the victims were killed execution-style. President Lula’s justice minister stated that Lula was horrified by the death toll and had not authorised the raid, which took place without federal approval. Rights investigators noted that in 2024, approximately 700 people were killed in police actions in Rio—nearly two per day, even before this incident. The episode underscored the persistence of militarised and largely unaccountable security practices, rooted in decades of mano dura policing. Lula’s administration, however, has publicly condemned the use of excessive force and pledged to pursue meaningful reforms in public security policy.

In short, Brazil’s picture is mixed. Bolsonarismo (Bolsonaro’s movement) still holds sway in many state capitals, and violence remains high. But Lula’s presidency so far shows more emphasis on rebuilding institutions and fighting inequality than on authoritarian control. Brazil’s democracy has shown resilience: after the coup attempt, support for democracy actually peaked among the public. Lula himself has publicly affirmed free speech and criticised right-wing attacks, reversing some of Bolsonaro’s polarising rhetoric. Thus, we can view Brazil as democratic, albeit fragile. The major ongoing concerns are police brutality and crime – which are treated as security policy issues more than political power grabs by the president.

However, although Lula’s third term has been marked by a renewed emphasis on social justice, labour rights, and environmental protection, it has also been coupled with a discourse that often frames politics as a moral battle between the people and entrenched elites. This populist tone has reinforced his image as a defender of ordinary Brazilians while simultaneously deepening political polarisation and straining institutional checks and balances. His leadership style tends to concentrate moral and political authority around his persona, blending pragmatic governance with an appeal to popular sentiment. Even though Lula continues to operate within democratic frameworks, this personalisation of power highlights the persistent tension between populist mobilisation and institutional restraint in Brazil’s fragile democracy.

Mexico’s case is more worrisome. Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO, 2018–2024), a self-declared leftist populist, implemented a dramatic concentration of power. By 2024 his ruling Morena party controlled the presidency, both houses of Congress, and most state governorships. His government pushed through constitutional amendments that bolstered the executive and weakened independent checks. By the end of his term, his party had achieved full control of the executive branch, both chambers of Congress, and most subnational states, and it overhauled the judiciary and strengthened the military through reforms aimed at executive aggrandisement and weakening checks and balances. In plain terms, AMLO used his majority to rewrite rules in his favour.

AMLO’s populist rhetoric was central to this process. He constantly framed his campaign as a fight against corrupt “elites” and the “old” political order. Slogans like “Por el bien de todos, primero los pobres” (For the good of all, first the poor) became rallying cries. On the surface, that populist welfare agenda – pensions for seniors, higher minimum wage, social programmes – delivered what could be perceived as real results. Poverty fell sharply: by 2024 over 13.4 million fewer Mexicans lived below the poverty line, a historic 26% drop. These benefits helped AMLO maintain high approval from his base. Yet a closer look reveals a more complex picture. Independent analyses show that much of this reduction is linked to temporary cash transfers and post-pandemic economic recovery rather than structural improvements in wages, education, or healthcare. Inequality and informality remain deeply entrenched, and millions continue to rely on precarious, low-paid work. Moreover, Mexico’s social spending has not been matched by investments in institutional capacity or transparency, raising concerns that short-term welfare gains may mask longer-term fragility. In this sense, López Obrador’s populist social model contrasted starkly with its narrative of transformation: it has lifted incomes in the immediate term but done little to strengthen the foundations of sustainable, equitable development.

Also the same rhetoric that promised to empower the poor also justified undermining institutions. AMLO’s blend of social policy with authoritarian tactics created a downward trend in freedoms. He openly clashed with autonomous agencies and critical media, called judges “traitors,” and even moved to punish an independent Supreme Court justice. AMLO began implementing his unique brand of populist governance, combining a redistributive fiscal policy with democratic backsliding and power consolidation. In 2024’s Freedom Index, Mexico plummeted from “mostly free” to “low freedom,” reflecting accelerated erosion of press freedom, judicial independence, and checks on the executive.

For example, AMLO mused about revoking autonomy of the election commission (INE) and packed federal courts with loyalists. He oversaw a lawsuit that temporarily replaced the anti-monopoly commissioner (though this was later reversed). Controversial judicial reforms were rammed through Congress with MORENA’s (National Regeneration Movement) supermajority. In the name of fighting corruption, AMLO and his party sidestepped democratic norms. By the time he left office, many prominent dissidents had been labelled enemies of the people, and civil-society watchdogs reported increasing self-censorship under fear of government reprisals.

Legitimate reforms vs. power grabs: Of course, AMLO’s administration did achieve significant social gains. His policies tripled the minimum wage and expanded social pensions for the elderly and students. From the left’s point of view, these are overdue redresses of inequality after decades of neoliberal policy. Nevertheless, one can also say that AMLO pursued these at the expense of Mexico’s democracy.

AMLO’s successor, Claudia Sheinbaum has largely extended the populist and centralising model of her predecessor. Her government has expanded the same welfare policies – including pensions for the elderly, youth scholarships, and agricultural subsidies – which continue to secure her strong approval ratings. At the same time, she has pursued a more nationalist economic strategy, favouring the state over private or renewable investment, a move seen by many as ideologically driven rather than economically sound.

Her administration’s approach to governance has reinforced concerns about democratic backsliding. Within months of taking power, her party used its congressional majority to pass a sweeping judicial reform allowing for the election of nearly all judges, a measure widely interpreted as undermining judicial independence. She also oversaw the dismantling of Mexico’s autonomous transparency and regulatory agencies, institutions originally created to prevent executive overreach after decades of one-party rule. Her rhetoric, while measured compared to López Obrador’s, has nonetheless targeted independent electoral and judicial authorities as acting against the popular will. Violence against journalists and judicial pressure on the press have continued under her watch, suggesting a continuity of the authoritarian tendencies embedded in her predecessor’s style of governance. In effect, Sheinbaum has presented herself as the guardian of López Obrador’s so-called “Fourth Transformation”, but her actions increasingly blur the line between social reform and the consolidation of political control.

Meanwhile, MORENA, the ruling party, has evolved into a hegemonic political force that increasingly mirrors the old Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Having consolidated control over the presidency, Congress, and most governorships, MORENA now dominates the national political landscape with little meaningful opposition. Its supermajority has enabled constitutional changes that weaken autonomous regulators and reconfigure the judiciary in its favour. Efforts to overhaul the electoral system – including proposals to curtail proportional representation and cut funding for opposition parties – further tilt the playing field towards one-party dominance. The party’s control of state resources and vast social programmes has also revived the clientelism and political patronage once characteristic of PRI rule. Many regional elites and former PRI figures have joined MORENA’s ranks, expanding its reach through local alliances and personal networks. This combination of electoral dominance, state control, and populist legitimacy has left few institutional counterweights to its power. In practice, Mexico’s political system is sliding back towards the PRI-style arrangement it once fought to overcome: a single dominant party using popular mandates and social welfare to entrench its hold over the state while constraining the mechanisms of democratic accountability.

Colombia: Peace Agenda and Institutional Pushback

Colombia’s new president, Gustavo Petro (in office since August 2022), is the country’s first-ever leftist head of state. He campaigned on ending historical violence and inequality, reaching a definitive peace with guerrilla groups, and “transforming” Colombian society. To that end, Petro has pursued ambitious reforms – agrarian, labor, climate, and constitutional – some of which have hit roadblocks in Congress and the courts.

One flashpoint has been his call for a constitutional rewrite. Petro announced he would ask voters (via the 2026 legislative elections ballot) whether to convene a national constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. He argues that traditional institutions (Congress and the courts) repeatedly blocked key reforms – for instance, an environmental tax and a gender law were struck down as unconstitutional – and that only a direct mandate could implement his agenda. In his own words, he has framed the move as carrying out “the people’s mandate for peace and justice”, implicitly casting political opposition as elitist roadblocks. Arguably, under Colombia’s 1991 Constitution, a referendum on reform first requires legislation from Congress; the president alone cannot unilaterally change the constitution. Indeed, Petro’s coalition lost its majority in the Senate after the 2024 elections, and even has a minority in the House. That means he cannot force through a referendum law on his own.

Petro’s gambit is a stress test of Colombia’s institutions. Although Petro is popular with part of the electorate, and the checks and balances in the country have been holding– Congress and the Constitutional Court can still block overreach. Petro’s approval ratings hover around 37%, giving savvy opponents incentive to organise rallies or boycotts if he tries an end-run around Congress. Moreover, Colombia’s Constitutional Court has so far signalled it will strictly enforce procedural requirements before any reform, and it would likely strike down any effort to allow immediate presidential reelection (which the constitution currently bans). In fact, observers have flagged concern that Petro might push to permit his own re-election, raising alarm among civil society and international partners.

Thus far Petro has not succeeded in weakening institutions as Bolsonaro did in Brazil or Maduro in Venezuela. To the contrary, Colombia’s court and electoral tribunal have acted independently, even prosecuting members of Petro’s coalition for campaign irregularities. The country’s strong judicial branch remains a bulwark. That said, the tone of politics has become extremely polarised and personal. After a recent assassination of a presidential candidate (son of former President Uribe), the campaign trail saw shrill accusations: Petro’s supporters often label their opponents “far-right extremists,” while his critics call him a “communist” or worse. This combustible rhetoric – on all sides – could jeopardise stability.

Colombia today embodies both promise and peril. Petro has introduced progressive initiatives (such as a new climate ministry and child allowances) that appeal to many, but he also openly questions the role of old elites and considers dramatic institutional change. His proposals have not yet realised an authoritarian shift, but they have tested the separation of powers. The situation is dynamic: if Petro tries to override constraints, Colombia’s existing democratic guardrails (courts, Congress, watchdogs) will likely react strongly. The key question will be whether Colombia can channel legitimate popular demands through its institutions without them buckling under pressure.

El Salvador: The Bukele Model of “Punitive Populism”

El Salvador stands apart. President Nayib Bukele (in power since 2019, re-elected 2024) defies easy ideological labelling– he was not from the traditional leftist bloc – but his governance style has strong authoritarian features. His rise was fuelled by a promise to crush the country’s notorious gangs, and indeed El Salvador’s homicide rate plummeted under his rule. Bukele has remade a nation that was once the world’s murder capital. According to figures, over 81,000 alleged gang members have been jailed since 2022 – about one in 57 Salvadorans – and Bukele enjoys sky-high approval ratings (around 90%) from citizens tired of crime. These results have been touted as proof that his “iron fist” strategy of mass arrests and harsh prison sentences (the world’s largest incarceration rate) has worked. In this sense, Bukele’s firm grip on security is seen by many supporters as a legitimate reform: a state that delivers safety, even at the cost of civil liberties.

However, the democratic trade-offs have been extreme. Since 2022, Bukele has ruled largely by decree under a perpetual state of emergency, suspending key constitutional rights (due process, privacy, freedom of assembly). Criminal suspects – including minors – are arrested en masse without warrants and often held in overcrowded prisons. The president has openly interfered in the judiciary: his pro-government legislators dismissed all members of the Supreme Court and Attorney General’s office in 2021–22, replacing them with loyalists. This allowed Bukele to evade the constitutional prohibition on immediate presidential re-election and secure a second term in 2024. Even ordinary political opposition has been effectively pulverised, party leaders disqualified, judges threatened, and dissenters harassed or driven into exile.

Human-rights groups accuse Bukele’s security forces of torture and disappearances of innocent people swept up in the dragnet. A 2024 Latinobarómetro survey found that 61% of Salvadorans fear negative consequences for speaking out against the regime – despite the fact that Bukele’s formal approval remains high. Many critics now call him a “social-media-savvy strongman” or “millennial caudillo”, suggesting he leads by personal charisma and social-media influence.

On the other hand, his defenders argue Bukele has simply done what past governments could not: restore order and invest in infrastructure (like child-care and tech initiatives) that were ignored for years. Indeed, El Salvador under Bukele has attracted foreign investment (notably in Bitcoin ventures) and even hosted international events like Miss Universe, as if to signal normalcy. But Bukele has built his legitimacy on the back of extraordinary measures that sideline democracy. Bukele’s popularity may export a brand of ‘punitive populism’ that leads other heads of state to restrict constitutional rights, and when (not if) public opinion turns, the country may find itself with no peaceful outlet for change. In other words, El Salvador’s example shows how quickly a welfare-and-security-oriented leader can morph into an authoritarian ruler once key institutions are neutered.

Venezuela: Consolidated Authoritarianism

Venezuela is the clearest example of democracy overtaken by authoritarianism. Over the past quarter-century, Hugo Chávez and his successor Nicolás Maduro have steadily dismantled democratic institutions, replacing them with a one-party state. Today Venezuela is widely recognised as a full electoral dictatorship, not an anomaly but a case study in how leftist populism can yield outright autocracy. The 2024 presidential election was the latest illustration: overwhelming evidence suggests the opposition actually won by a landslide, yet the regime hid the true vote counts, declared Maduro the winner with a suspicious 51% share, and reinstalled him for a third term. Venezuela’s leaders purposefully steered Venezuela toward authoritarianism. It is now a fully consolidated electoral dictatorship

Since then, Maduro’s government has stamped out virtually all resistance. Leading opposition figures have been harassed, jailed, or exiled. Opposition candidate María Corina Machado – who reportedly won twice as many votes as Maduro was banned by the Supreme Court from even running. New laws passed in late 2024 further chill dissent: for example, the “Simón Bolívar” sanctions law criminalises criticism of the state, and an “Anti-NGO” law gives authorities broad power to shut down civil-society groups if they receive foreign funds. All justice in Venezuela is now rubber-stamped by Maduro’s hand-picked judges.

Any pretense of pluralism has vanished. State media and pro-government mobs drown out or beat up remaining critics. Despite dire economic collapse and mass exodus (millions of Venezuelans have fled hunger and repression), Maduro governs with an iron grip. In short, Venezuela today is an example of ideological rhetoric (Chavismo, Bolivarian Revolution) entirely subsumed by power. It also serves as a caution: the veneer of elections and redistributive slogans can sometimes hide total dictatorship. (In Venezuela’s case, the “leftist” regime never even bothered to disguise its authoritarian turn.)

Legitimacy, Rhetoric, and Checks

Throughout these cases, a common theme emerges: populist rhetoric vs institutional reality. Leftist or progressive leaders often claim to champion the poor and marginalised – a message that resonates in societies scarred by inequality. Yet in practice, that rhetoric sometimes becomes a justification for concentrating power. AMLO spoke of a “fourth transformation” of Mexico to overcome the “old regime,” and applied that mission to reshape institutions. Petro invokes “the will of the people” to override what he calls elite obstruction. Lula’s Brazil has been less about overthrowing elites and more about undoing his predecessor’s policies. And Bukele promises safety so absolute that he deems dissent a luxury Salvadorans cannot afford.

Of course, leftist governments do enact genuine reforms. The region has seen expansions of social programmes, pensions, healthcare, and education in many countries. In a sense, voters rewarded candidates like Lula, Petro, and AMLO precisely because they promised change and delivered temporary benefits (scholarships, pensions, workers’ pay raises, etc.). But even well-meaning reforms can backfire if the manner of governing ignores constitutional limits.

Where was the line crossed from policy to autocracy? The answer varies. In Venezuela, it was crossed long ago. In El Salvador, it was in 2020 when the Supreme Court was neutered. In Mexico and Colombia, it might yet be crossed if current trends continue. Notably, independent institutions have played the decisive role. Brazil’s judiciary and congress checked Bolsonaro and remain intact under Lula; Colombia’s still-revolutionary courts have so far blocked Petro’s more radical ideas; under Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico’s courts remain constrained by the constitutional limits that formally prevent presidential re-election, yet her administration’s actions have significantly weakened judicial independence. By politicising judicial appointments and curbing the autonomy of oversight bodies, her government has consolidated influence over the very institutions meant to act as checks on executive authority. In practice, Mexico’s judiciary is now more vulnerable to political pressure than at any time since the end of PRI dominance, reflecting a growing concentration of power within the presidency and the ruling party. In contrast, Venezuela’s courts have no independence at all, and El Salvador’s were replaced wholesale.

This suggests that Latin America has not uniformly fallen back into classic authoritarianism under “leftist” governments. Instead, populist leaders of varying ideologies have tested democratic boundaries, and outcomes differ by country. Where institutions remained strong, they provided a buffer. Where institutions were undermined, democracy withered.

The Future of Democracy in Latin America

So what does the future hold? After a brief blip of improvement, democracy metrics in Latin America appear to be declining again. In 2023, a composite index actually rose slightly, driven by gains in Colombia (Free status by Freedom House) and Brazil. But by 2024 the region was “re-autocratising”, with rule-of-law slipping in Mexico and Peru, and older warning signs re-emerging across the continent.

Key factors will influence the coming years. On one hand, many Latin Americans remain hungry for security, equity, and an end to corruption – needs that populist leaders address. If such leaders deliver results (as Bukele did on crime), public tolerance for illiberal methods may persist. On the other hand, the region has a relatively robust civil society, and voters in countries like Brazil and Colombia have shown willingness to hold leaders accountable.

Balance is crucial. In well-functioning democracies, major changes do not require emergency decrees or friendly courts; they require compromise and open debate. The examples of Mexico and El Salvador show how quickly democratic norms can erode when populist leaders wield their mandate without restraint.

Ultimately, Latin America’s record is not hopeless, but neither is it fully reassuring. The early 2020s have demonstrated that both left-wing and right-wing populisms can strain democracy. Are we returning to authoritarianism under a leftist facade? – has no single answer. In countries like Venezuela, the answer is emphatically yes. In others, it is a warning under construction: Mexico and El Salvador caution us, Colombia is at a crossroads, and Brazil’s experience suggests that institutions can still provide meaningful checks on executive power, but their resilience is not guaranteed. The recent police raid in Rio de Janeiro, serves as a stark test for Lula’s commitment to reforming Brazil’s militarised public-security apparatus. How his government responds to this and similar incidents will be a critical measure of whether Brazil’s democratic institutions can withstand pressure from both public opinion and entrenched security structures, or whether longstanding legacies of unchecked police power will continue to erode accountability.

For the future of the region, the lesson is that rhetoric alone cannot safeguard democracy. Even popular leaders must respect independent judiciaries, free press, and electoral integrity. If those pillars are allowed to crumble, Latin America’s democratic gains will fade. The coming years will test whether each country’s citizens insist on true democratic practice or allow the allure of strong leadership to override constitutional limits.

![Heavily damaged buildings are reflected in a water basin in the Sheikh Radwan neighborhood of Gaza City on October 22, 2025. [File: Omar Al-Qattaa/AFP]](https://i0.wp.com/occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/000_79L4482-1762593853.jpg?w=640&ssl=1)

![A boy fills a plastic bottle with water inside a camp for displaced Palestinians at a school-turned-shelter in Al-Rimal neighbourhood of Gaza City on November 5, 2025. [File: Omar Al Qattaa]](https://i0.wp.com/occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/000_834T3FC-1762594052.jpg?w=640&ssl=1)