Bangladesh issues global call on Rohingya crisis

Dhaka hopes a conference can provide solutions to the aid crisis facing Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

Source link

Dhaka hopes a conference can provide solutions to the aid crisis facing Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

Source link

Investigators name senior figures among those responsible for alleged abuses at detention facilities.

United Nations investigators say they have gathered evidence of systematic torture in Myanmar’s detention facilities, identifying senior figures among those responsible.

The Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM), set up in 2018 to examine potential breaches of international law, said on Tuesday that detainees had endured beatings, electric shocks, strangulation and fingernail removal with pliers.

“We have uncovered significant evidence, including eyewitness testimony, showing systematic torture in Myanmar detention facilities,” Nicholas Koumjian, head of the mechanism, said in a statement accompanying its 16-page report.

The UN team said some prisoners died as a result of the torture.

It also documented the abuse of children, often detained unlawfully as proxies for their missing parents.

According to the report, the UN team has made more than two dozen formal requests for information and access to the country, all of which have gone unanswered. Myanmar’s military authorities did not respond to media requests for comment.

The military has repeatedly denied committing atrocities, saying it is maintaining peace and security while blaming “terrorists” for unrest.

The findings cover a year that ended on June 30 and draw on information from more than 1,300 sources, including hundreds of witness accounts, forensic analysis, photographs and documents.

The IIMM said it identified high-ranking commanders among the perpetrators but declined to name them to avoid alerting those under investigation.

The report also found that both government forces and armed opposition groups had committed summary executions. Officials from neither side of Myanmar’s conflict were available to comment.

The latest turmoil in Myanmar began when a 2021 military coup ousted an elected civilian government, sparking a nationwide conflict. The UN estimates tens of thousands of people have been detained in efforts to crush dissent and bolster the military’s ranks.

Last month, the leader of the military government, Min Aung Hlaing, ended a four-year state of emergency and appointed himself acting president before planned elections.

The IIMM’s mandate covers abuses in Myanmar dating back to 2011, including the military’s 2017 campaign against the mostly Muslim Rohingya, which forced hundreds of thousands of members of the ethnic minority to flee to Bangladesh, and postcoup atrocities against multiple communities.

The IIMM is also assisting international legal proceedings, including cases in Britain. However, the report warned that budget cuts at the UN could undermine its work.

“These financial pressures threaten the Mechanism’s ability to sustain its critical work and to continue supporting international and national justice efforts,” it said.

A student uprising shook Bangladesh, toppling its most powerful leader. After 15 years in office, Sheikh Hasina’s grip on power broke under the pressure of a movement that began with a dispute over government jobs, and ended with her fleeing the country. To mark the anniversary, here’s the first episode of 36 July: Uprising in Bangladesh, the new season of Al Jazeera Investigates.

Thousands rallied in Dhaka, Bangladesh, to mark one year since nationwide protests forced former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to resign. The 2024 uprising began over quota reforms but turned deadly, with over 1,400 people killed. The country’s interim leader announced new elections will be held in February.

Published On 5 Aug 20255 Aug 2025

Interim leader says first national polls since overthrow of Sheikh Hasina to be held in February.

Bangladesh’s interim leader, Muhammad Yunus, has unveiled a roadmap of democratic reforms as the nation marks a year since a mass uprising toppled Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

Rallies, concerts and prayer sessions were held in the capital, Dhaka, on Tuesday as people in the South Asian nation celebrated what many called the country’s “second liberation” after its independence from Pakistan in 1971.

The anniversary culminated with Yunus, the 85-year-old Nobel Peace Prize laureate presiding over Bangladesh’s democratic overhaul, announcing that he would write to the chief election commissioner requesting that national elections be arranged before Ramadan in February.

“We will step into the final and most important phase after delivering this speech to you, and that is the transfer of power to an elected government,” he said.

Yunus had previously said elections would be held in April, but key political parties have been demanding he hold them earlier and before the Islamic holy month in the Muslim-majority nation of 170 million people.

“On behalf of the government, we will extend all necessary support to ensure that the election is free, peaceful and celebratory in spirit,” the interim leader added.

Hasina’s rule saw widespread human rights abuses, including mass detentions and extrajudicial killings of her political opponents.

Protests against Hasina’s rule began on July 1, 2024, with university students calling for changes to a quota system for public sector jobs. They culminated on August 5, 2024, when thousands of protesters stormed Hasina’s palace as she escaped by helicopter.

Hasina, 77, fled to India and remains there. She has defied court orders to attend her ongoing trial on charges amounting to crimes against humanity.

On Tuesday, Yunus called for people to seize the “opportunity” for reform. He also warned about people whom he said sought to undermine the nation’s gains, saying, “The fallen autocrats and their self-serving allies remain active, conspiring to derail our progress.”

“Dialogue continues with political parties and stakeholders on necessary reforms, including the political and electoral systems,” he added.

Those gathered in Dhaka included families of those killed in the crackdowns on last year’s protests. Police were on high alert throughout the city with armoured vehicles patrolling the streets to deter any attempt by Hasina’s banned Awami League party to disrupt the day’s events.

Protesters also welcomed Yunus’s move to formally read out the July Declaration, a 28-point document that seeks to give constitutional recognition to the 2024 student-led uprising. He added that trials for those responsible for the July killings of 2024 were progressing swiftly.

Fariha Tamanna, 25, said it was “deeply satisfying” to hear the government “acknowledge the uprising”. “There’s still a long road ahead. So many wrongs continue,” she told the AFP news agency at a rally. “But I still hold on to hope.”

The Stream examines how Bangladesh handles political uncertainty a year after youth protests toppled Sheikh Hasina.

We explore how Bangladesh is navigating political uncertainty one year after youth-led protests ended Sheikh Hasina’s long rule. In 2024, young Bangladeshis took to the streets, demanding change and forcing a political reckoning. A year later, the country sits in a delicate balance. We examine what the future looks like through the eyes of its young people.

Presenter: Stefanie Dekker

Guests:

Apurba Jahangir – Deputy press secretary in the interim government of Bangladesh

Ifti Nihal – Content creator

Dhaka, Bangladesh – Sinthia Mehrin Sokal remembers the blow to her head on July 15 last year when she, along with thousands of fellow students, marched during a protest against a controversial quota system in government jobs in Bangladesh’s capital, Dhaka.

The attack by an activist belonging to the student wing of the then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League party left Sokal – a final-year student of criminology at the University of Dhaka – with 10 stitches and temporary memory loss.

A day later, Abu Sayed, another 23-year-old student, was protesting at Begum Rokeya University in the Rangpur district, about 300km (186 miles) north of Dhaka, when he was shot by the police. A video of him, with his arms outstretched and collapsing on the ground moments later, went viral, igniting an unprecedented movement against Hasina, who governed the country with an iron fist for more than 15 years before she was toppled last August.

Students from schools, colleges, universities and madrassas took to the streets, defying a brutal crackdown. Soon, the young protesters were joined by their parents, teachers and other citizens. Opposition parties, including the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, lent crucial support, forming an unlikely united front against Hasina’s government.

“Even students in remote areas came out in support. It felt like real change was coming,” Sokal told Al Jazeera.

On August 5, 2024, as tens of thousands of protesters stormed Hasina’s palatial residence and offices in Dhaka, the 77-year-old leader boarded a military helicopter and fled to neighbouring India, her main ally, where she continues to defy a Bangladesh court’s orders to face trial for crimes against humanity and other charges.

By the time Hasina fled, more than 1,400 people had been killed, most when government forces fired on protesters, and thousands of others were wounded, according to the United Nations.

Three days after Hasina fled, the protesters installed an interim government, on August 8, 2024, led by the country’s only Nobel laureate, Muhammad Yunus. In May this year, the interim government banned the Awami League from any political activity until trials over last year’s killings of the protesters concluded. The party’s student wing, the Chhatra League, was banned under anti-terrorism laws in October 2024.

Yet, as Bangladesh marks the first anniversary of the end of Hasina’s government on Tuesday, Sokal said the sense of unity and hope that defined the 2024 uprising has given way to disillusionment and despair.

“They’re selling the revolution,” she said, referring to the various political groups now jostling for power ahead of general elections expected next year.

“The change we fought for remains out of reach,” said added. “The [interim] government no longer owns the uprising.”

Yunus, the 85-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner presiding over Bangladesh’s democratic overhaul, faces mounting political pressure, even as his interim government seeks consensus on drafting a new constitution. Rival factions that marched shoulder to shoulder during anti-Hasina protests are now locked in political battles over the way forward for Bangladesh.

On Tuesday, Yunus is expected to unveil a so-called July Proclamation, a document to mark the anniversary of Hasina’s ouster, which will outline the key reforms that his administration argues Bangladesh needs – and a roadmap to achieve that.

But not many are hopeful.

“Our children took to the streets for a just, democratic and sovereign Bangladesh. But that’s not what we’re getting,” said Sanjida Khan Deepti, whose 17-year-old son Anas was shot dead by the police during a peaceful march near Dhaka’s Chankharpul area on August 5, 2024. Witnesses said Anas was unarmed and running for cover when a police bullet struck him in the back. He died on the spot, still clutching a national flag.

“The reforms and justice for the July killings that we had hoped – it’s not duly happening,” the 36-year-old mother told Al Jazeera. “We took to the streets for a better, peaceful and just country. If that doesn’t happen, then what was my son’s sacrifice for?”

Others, however, continue to hold firm in their trust in the interim government.

“No regrets,” said Khokon Chandra Barman, who lost almost his entire face after he was shot by the police in the Narayanganj district.

“I am proud that my sacrifice helped bring down a regime built on discrimination,” he told Al Jazeera.

Barman feels the country is in better hands now under the Yunus-led interim government. “The old evils won’t disappear overnight. But we are hopeful.”

Atikul Gazi agreed. “Yunus sir is capable and trying his best,” Gazi told Al Jazeera on Sunday. “If the political parties fully cooperated with him, things would be even better.”

The 21-year-old TikToker from Dhaka’s Uttara area survived being shot at point-blank range on August 5, 2024, but lost his left arm.

A selfie video of him smiling, despite missing an arm, posted on September 16 last year, went viral, making him a symbol of resilience.

“I’m not afraid… I’m back in the field. One hand may be gone, but my life is ready to be offered anew.”

Others are less optimistic. “That was a moment of unprecedented unity,” said Mohammad Golam Rabbani, a professor of history at Jahangirnagar University on the outskirts of Dhaka.

Rabbani had recited a poem during a campus protest on July 29, 2024. Speaking at an event last month to commemorate the uprising, he said: “Safeguarding that unity should have been the new government’s first task. But they let it slip.”

The coalition of students, professionals and activists, called Students Against Discrimination, that brought down Hasina’s government, began to fragment even before Yunus took charge.

Hoping to cash in on massive anti-Awami League sentiment, the main opposition BNP has been demanding immediate elections since the uprising. But parties like the National Citizens Party, formed by student leaders of the 2024 protests, and Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami want deeper structural reforms before any vote is held.

To reconcile such demands, the Yunus administration formed a National Consensus Commission on February 12 this year. Its mandate is to merge multiple reform agendas outlined by expert panels into a single political blueprint. Any party or coalition that wins the next general election must formally pledge to implement this charter.

But so far, the meetings of the commission have been marked by rifts and dissent, mainly over having a bicameral parliament, adopting proportional representation in both its houses, and reforming the appointment process for key constitutional bodies by curbing the prime minister’s influence to ensure greater neutrality and non-partisanship.

“If the political forces fail to agree on reforms, instability could increase,” warned analyst Rezaul Karim Rony.

But Mubashar Hasan, adjunct fellow at Western Sydney University’s Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative, thinks a political deadlock is “unlikely”, and that most stakeholders seem to be moving towards elections next year.

Hasan, however, remains sceptical of the reforms themselves, calling them a “cosmetic reset”.

“There’ll be some democratic progress, but not a genuine shift,” he told Al Jazeera. He pointed out that the Awami League, which once represented millions, remains banned – a fact that some analysts have pointed out could weaken the credibility of Bangladesh’s electoral democracy.

Deepti, who lost her teenage son during the protests, said political parties are scrambling for power, and not acting against the people who enabled Hasina’s brutal repression during last year’s protests.

“Most of the officials and law enforcement members involved in the violence are still at large, while political parties are more focused on grabbing power,” she told Al Jazeera.

Sharif Osman Bin Hadi, the spokesman for Inquilab Manch (Revolution Front), a non-partisan cultural organisation inspired by the uprising, warned that elections without justice and reforms would “push the country back into the jaws of fascism”.

His group, with more than 1,000 members in 25 districts, organises poetry readings, exhibitions and street performances to commemorate the 2024 uprising and demand accountability, amid widespread concerns over deteriorating law and order across the country.

While the police remain discredited and are yet to recover from the taint of complicity in perpetuating Hasina’s strong-armed governance, military soldiers are seen patrolling Bangladesh’s streets, armed with special power to arrest, detain and, in extreme cases, even fire on those breaking the law.

In a recent report, rights group Odhikar said at least 72 people were killed and 1,677 others injured in incidents of political violence between April and June this year. The group also documented eight alleged extrajudicial killings during this period involving the police and notorious paramilitary forces like the Rapid Action Battalion.

Other crimes have also surged.

Police recorded 1,587 cases of murder between January and May this year, a 25 percent rise from the same period last year. Robbery nearly doubled to 318, while crimes against women and children topped 9,100. Kidnapping and robbery have also seen a spike.

“Mob justice and targeted killings have surged, many with political links,” Md Ijajul Islam, the executive director of the nonprofit Human Rights Support Society, told Al Jazeera. “Unless political parties rein in their activists, a demoralised police won’t be able to contain it.”

The demoralisation within the police stems mostly from the 2024 uprising itself, when more than 500 police stations were attacked across Bangladesh and law enforcement officials were missing from the streets for more than a week.

“The force had to restart from a morally-broken state,” Ijajul said.

Several police officers Al Jazeera spoke to at the grassroots level pointed to another problem: the collapse of what they called an informal political order in rural areas.

“During the Awami League era, police often worked in tandem with the ruling party leaders, who mediated local disputes,” said a senior police officer at the Roumari police station in the Kurigram district near the border with India.

“That structure is gone. Now multiple factions – from BNP, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami and others – are trying to control markets, transport hubs and government tenders,” he said on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak to the media.

In Dhaka, things are no better.

“Every day, managing street protests has become one of our major duties,” Talebur Rahman, a deputy commissioner with the Dhaka Metropolitan Police, told Al Jazeera.

“It feels like Dhaka has become ‘a city of demonstrations’ – people break into government offices, just to make their demands heard,” said Rahman.

Still, Rahman claimed the city’s law and order situation was better than immediately after the 2024 uprising. In a televised interview on July 15, Yunus’s spokesperson, Shafiqul Alam, also claimed that “if you consider overall statistics, things are stabilising”, he told Somoy Television network, referring to law and order in Dhaka.

Alam said that many people who were denied justice for years, including during the uprising, are now coming forward to register cases.

Some agree.

“Things are slowly improving,” said 38-year-old rickshaw-puller Mohammad Shainur in Dhaka’s upscale Bashundhara neighbourhood.

The economy, for one, has shown some positive signs. Bangladesh is the world’s 35th largest economy and the second in South Asia – mainly driven by its thriving garment and agriculture industries.

Foreign reserves climbed from more than $24bn in May 2024, to nearly $32bn by June this year, helped by a crackdown on illicit capital flight, record remittances and new funding from the International Monetary Fund. Inflation, which peaked at 11.7 percent in July 2024, dropped to 8.5 percent by June this year.

But there is also widespread joblessness, with the International Labour Organization saying that nearly 30 percent of Bangladesh’s youth are neither employed nor pursuing education. Moreover, a 20 percent tariff announced by the United States, the largest buyer of Bangladesh’s garments, also threatens the livelihood of 4 million workers employed in the key sector.

Back in Dhaka, Gazi is determined to preserve the memory of 2024’s protests.

“Let the people remember those martyred in the uprising, and those of us who were injured,” he told Al Jazeera. “We want to remain as living symbols of that freedom.”

“I lost one hand, and I have no regrets. I will give my life if needed – this country must be governed well, no matter who holds power.”

The July Mass Uprising Day has been categorised under the Cabinet Division’s “Ka” category, which includes national and international days of major significance. These days often involve extensive ceremonies, official participation, and may be observed as government holidays.

The day will be officially celebrated every year.

The decision was made at a meeting of the advisory council at the State Guest House Jamuna. After the meeting, Cultural Affairs Adviser Mostofa Sarwar Farooki told reporters at the Foreign Service Academy that a preliminary decision had been made to celebrate August 5th as the Student-People Uprising Day.

August 5th is going to be a national day, so the Student-People Uprising Day will be celebrated every year in the future, he said.

The Awami League regime fell on August 5th 2024 amid a mass uprising.

On August 5th 2024, Bangladesh’s former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina left her official residence as a violent mob was marching towards it. With a serious threat arising over her security, Ms Hasina fled the country.

A roundup of some of last week’s events.

Source link

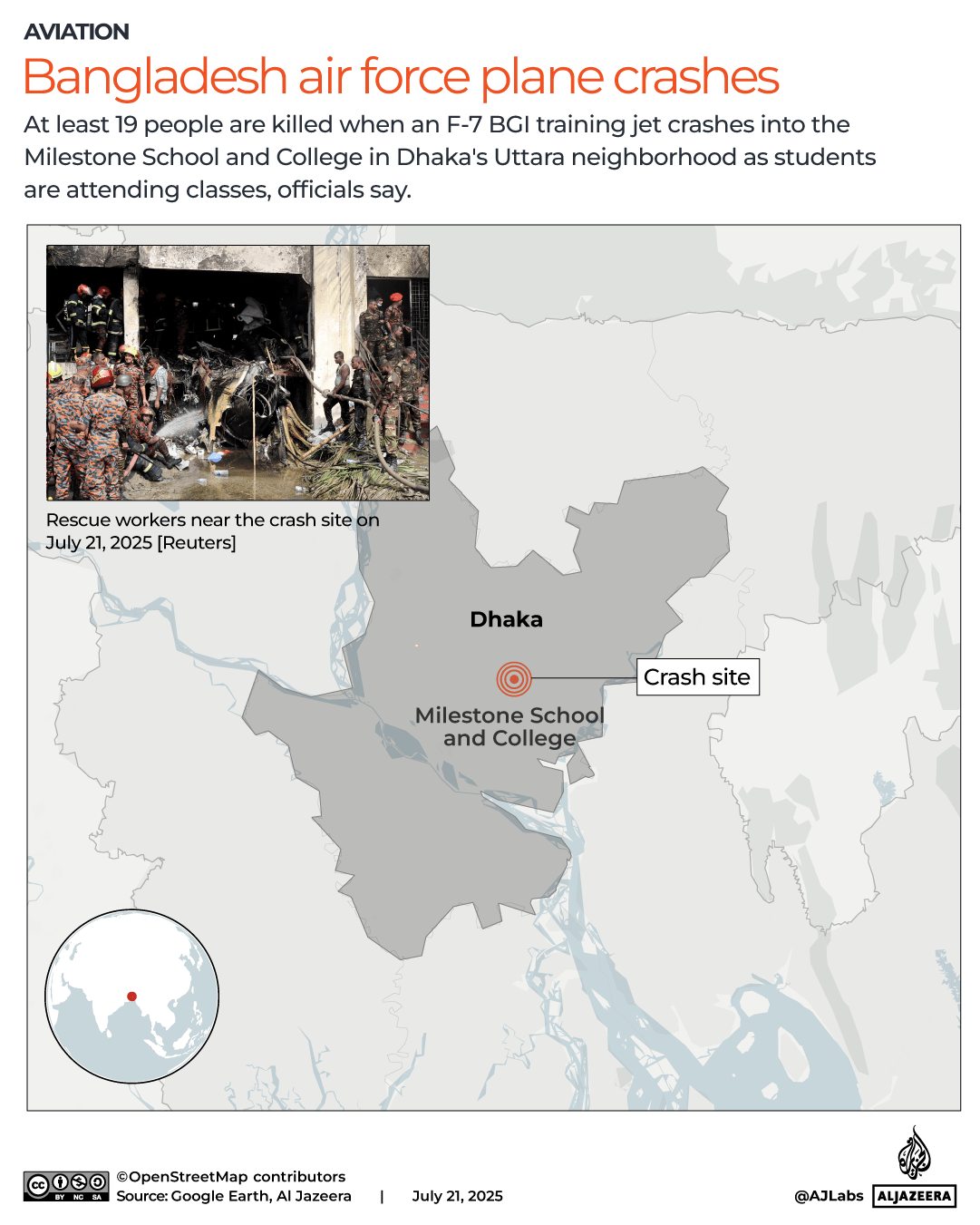

A Bangladesh air force training jet has crashed into a school campus, killing at least 19 people.

Here’s the latest we know:

“Bangladesh Air Force’s F-7 BGI training aircraft crashed in Uttara. The aircraft took off at 13:06 [07:06 GMT],” the Bangladesh military’s public relations team said.

Local media reported that the plane crashed at about 1:30pm.

Videos emerged of the aftermath of the crash, showing a fire, as well as plumes of thick smoke rising into the sky as people watched from a distance.

The crash marks the deadliest aviation incident in Bangladesh since the 1984 crash of a plane travelling from Chattogram to Dhaka killed all 49 people on board.

Last month, an Air India passenger plane crashed into a medical college hostel in India’s Ahmedabad city, killing 241 of the 242 people on board as well as 19 people on the ground. This incident marked the world’s worst aviation disaster in a decade.

The plane crashed into the campus of Milestone School and College, a private school in the northern Dhaka neighbourhood of Uttara.

Footage shared online after the crash showed the point where the aircraft had crashed into the side of a building, leaving a gaping hole.

At the time of the crash, students were taking tests or attending regular classes.

According to the information available on the school’s website, there are 6,000 enrolled students at Milestones.

The F-7 BGI is a light, “multi-role” fighter aircraft manufactured by the Chinese Chengdu Corporation.

Multi-role fighter aircraft are built to perform several “roles” in combat, including air-to-air combat, aerial bombing, reconnaissance, and suppression of air defences.

The BGI was billed as the most advanced F-7 when Bangladesh bought 36 of them in 2022.

It had been upgraded according to Bangladesh’s specifications.

At least 19 people have died and more than 100 have been injured, based on data from multiple hospitals.

Authorities have not released details about those who have died or are injured.

“A third-grade student was brought in dead, and three others, aged 12, 14 and 40, were admitted to the hospital,” Bidhan Sarker, head of the burn unit at the Dhaka Medical College and Hospital, told the Reuters news agency.

More than 50 people, including children, were admitted to the hospital with burn injuries following the crash, a doctor at the National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery told reporters.

An emergency hotline has been set up at the institute, Muhammad Yunus, the head of Bangladesh’s interim government, wrote in a post on X.

Local media reported that several of the injured were transported to the Combined Military Hospital (CMH) through air force helicopters.

The army, air force, police and the Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB), a paramilitary border security force, are working together on rescue efforts, local media reported.

Eight units of the fire service are working to contain the fire, the Dhaka Tribune reported.

Yunus said the government is taking all “necessary measures” in the aftermath of the crash.

He posted on his X account that the bodies of those who can be identified will be returned to their families as soon as possible.

Those whose identities cannot be immediately confirmed will undergo DNA testing, after which their remains will also be released to their families.

In another post, Yunus shared the emergency contacts of different rescue departments regarding missing school students.

Mostly students killed and more than 50 wounded as training aircraft crashes into campus in capital Dhaka.

At least 19 people have been killed as a Bangladesh air force training aircraft crashed into a college and school campus in capital Dhaka, a fire services official and local media reports said.

The F-7 BGI aircraft crashed into the campus of Milestone School and College in Dhaka’s Uttara neighbourhood at about 1pm (07:00 GMT), when students were taking tests or attending regular classes.

More than 50 people, including children and adults, were hospitalised with burns after the crash, a doctor at the National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery told reporters.

Videos of the aftermath of the crash showed a big fire near a lawn emitting a thick plume of smoke into the sky, as crowds watched from a distance.

Firefighters sprayed water on the mangled remains of the plane, which appeared to have rammed into the side of a building, damaging iron grills and creating a gaping hole in the structure.

“A third-grade student was brought in dead, and three others, aged 12, 14 and 40, were admitted to the hospital,” Bidhan Sarker, head of the burn unit at the Dhaka Medical College and Hospital, where some victims were taken, told the Reuters news agency.

Social media videos showed people screaming and crying as others tried to comfort them.

“When I was picking [up] my kids and went to the gate, I realised something came from behind … I heard an explosion. When I looked back, I only saw fire and smoke,” Masud Tarik, a teacher at the school, told Reuters.

Muhammad Yunus, head of Bangladesh’s interim government, said “necessary measures” would be taken to investigate the cause of the accident and “ensure all kinds of assistance”.

“The loss suffered by the air force … students, parents, teachers and staff, and others in this accident is irreparable,” he said.

Yunus also announced that an emergency hotline has been activated at the National Institute of Burn and Plastic Surgery in the wake of the crash.

The Bangladesh Red Crescent Society called for donations for those injured.

The incident came a little over a month after an Air India plane crashed on top of a medical college hostel in neighbouring India’s Ahmedabad city, killing 241 of the 242 people on board and 19 on the ground, marking the world’s worst aviation disaster in a decade.

A roundup of some of last week’s events.

Source link

Hundreds of thousands of supporters of Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party took part in a rally in the capital, Dhaka, demanding an overhaul of the electoral system.

The South Asian nation is expected to head to the polls next year as it stands at a crossroads after the ouster of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

On Saturday, Jamaat-e-Islami placed a seven-point demand on the country’s interim government headed by Muhammad Yunus to ensure a free, fair and peaceful election, justice for all mass killings, essential reforms and the proclamation and implementation of a charter involving last year’s mass uprising.

The party also said it wants the introduction of a proportional representation system in the election.

Thousands of supporters of Jamaat-e-Islami spent the night on the Dhaka University campus before the rally.

On Saturday morning, braving the sweltering heat, they continued to stream towards Suhrawardy Udyan, a historical site where the Pakistani army surrendered to a joint force of India and Bangladesh on December 16, 1971, ending the nine-month war.

“We are here for a new Bangladesh, where Islam would be the guiding principle of governance, where good and honest people will rule the country, and there will be no corruption,” said Iqbal Hossain, 40.

“We will sacrifice our lives, if necessary, for this cause.”

Some demonstrators wore T-shirts bearing the party’s logo, others sported headbands inscribed with its name, while many displayed metallic badges shaped like a scale – the party’s electoral symbol.

Many young supporters in their 20s and 30s were also present.

“Under Jamaat-e-Islami, this country will have no discrimination. All people will have their rights. Because we follow the path of the holy book – Quran,” said Mohidul Morsalin Sayem, a 20-year-old student.

“If all the Islamist parties join hands, soon, nobody will be able to take power from us.”

The party’s chief, Shafiqur Rahman, said the country’s struggle in 2024 was to eliminate “fascism”, but this time, there would be another fight against corruption and extortion.

“How will the future Bangladesh look like? There will be another fight … We will do whatever is necessary and win that fight,” Rahman said.

After Bangladesh’s independence, Jamaat, which sided with Pakistan during Bangladesh’s war of independence in 1971, was banned.

It later re-emerged and registered its best electoral performance in 1991 when it secured 18 seats.

The party also joined a coalition government in 2001, but failed to build lasting popular support.

While Prime Minister Hasina was in power from 2009 until she was toppled in student-led protests last year and fled to India, top leaders of Jamaat-e-Islami were either executed or jailed on charges of crimes against humanity and other serious crimes in 1971.

Last month, the Supreme Court restored the party’s registration, paving the way for its participation in elections slated for next April.

In a statement on X, Hasina’s Awami League party reacted sharply to Yunus’s government allowing Saturday’s rally.

The statement said the move “marks a stark betrayal with the national conscience and constitutes a brazen act of undermining millions of people – dead and alive – who fought against the evil axis [in 1971]”.

The Yunus-led administration has banned the Awami League, and Hasina has been in exile in India since last August. She faces charges of crimes against humanity.

Heavy police presence at Faridpur rally after violence erupts between security forces and supporters of ousted PM Sheikh Hasina.

Authorities in Bangladesh have imposed heavy security measures to prevent a repeat of further political violence, after clashes between security forces and supporters of deposed Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina left four people dead and more than 50 injured.

Hundreds of police were deployed Thursday to the site of a planned rally in Faridpur by the National Citizen Party (NCP), a new political party formed by students who spearheaded the unrest that ousted longtime leader Hasina last year, local media reported. Their presence underlined the volatile political tensions that remain in the divided country nearly one year on from the mass protests that toppled Hasina from power.

On Wednesday, an NCP rally in Gopalganj district, Hasina’s ancestral home and a stronghold for her support base, erupted in violence when supporters of her Awami League party tried to disrupt the event.

Four people were killed and more than 50 were injured in the violence, local media reported, citing police.

Footage from Gopalganj showed pro-Hasina activists armed with sticks setting upon police and lighting vehicles on fire as NCP leaders arrived in vehicles at the party’s “March to Rebuild the Nation” event commemorating the uprising against Hasina.

More than 1,500 police, along with army and border guard personnel, were deployed to respond to the violence, the Dhaka Tribune reported, citing a police report. Armed personnel carriers were seen patrolling the streets as security forces responded to the unrest.

The English-language Daily Star, citing Gopalganj civil surgeon Abu Sayeed Md Faruk, named the four dead as Dipto Saha, Ramzan Kazi, Sohel and Emon. The newspaper reported that hospital staff had said that eight others were being operated on for bullet wounds.

Home Affairs adviser Jahangir Alam Chowdhury said that 10 police personnel were also injured in the violence, local media reported. He added that 25 people had been arrested over the unrest.

The streets of Gopalganj were quiet on Thursday, with shops closed and few vehicles on the road, the Dhaka Tribune reported, as authorities imposed a curfew on the district in response to the violence.

The violence in Gopalganj has underlined the volatile divisions that remain in Bangladesh nearly a year after Hasina was forced to resign, fleeing to exile on a helicopter to India, as the interim government struggles to ensure security.

Wednesday’s clashes drew promises of a harsh response from the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus that has governed the country since Hasina’s ouster last August.

Yunus said in a statement Wednesday that the attempt by Hasina’s supporters to disrupt the NCP rally was “a shameful violation of their fundamental rights”, and warned that the violence would “not go unpunished”.

The government said on Thursday that it had established a committee to investigate the violence, which would be chaired by Nasimul Ghani, senior secretary of the Ministry of Home Affairs, and report its findings within two weeks.

Despite its promises to crack down on those responsible, Yunus’s government has faced criticism for failing to deliver security in the divided country.

Hasina’s Awami League party, which authorities banned in May, posted a number of statements on social media platform X condemning the violence, including one saying that all the gunshot victims were supporters of the party. It blamed the interim government for the deaths and injuries.

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), one of two parties, alongside the Awami League, that have traditionally dominated Bangladeshi politics, also criticised the government on Thursday over the violence, saying it had failed to maintain law and order.

Meanwhile, the right-wing Jamaat-e-Islami party condemned the attacks on the NCP and announced protests of its own.

Earlier this month, Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal indicted Hasina and two senior officials over alleged crimes against humanity linked to a deadly crackdown on protesters during the uprising against her rule. In a separate, earlier ruling, Hasina – who lives in self-imposed exile in India – was sentenced in absentia to six months in prison for contempt of court by the tribunal.

On July 8, Indian Chief of Defence Staff Anil Chauhan delivered a pointed message at the Observer Research Foundation in New Delhi, raising alarms over a budding alignment of strategic interests between China, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

The general cautioned that such a trilateral convergence, if it gains traction, could have serious implications for India’s security and disrupt the regional balance of power.

His remarks came in the wake of a widely circulated photograph from Kunming, China, showing diplomats from the three nations meeting during the inaugural trilateral talks held alongside regional economic forums. While the meeting was officially billed as a diplomatic engagement, the image has sent ripples through India’s strategic community.

Bangladesh, clearly aware of the sensitivities involved, has moved swiftly to contain the narrative. Touhid Hossain, foreign affairs adviser to Dhaka’s interim government, publicly disavowed any intention of joining bloc-based or adversarial alliances. Dhaka reiterated that its foreign policy remains firmly nonaligned and anchored in sovereign autonomy.

Despite these assurances, New Delhi’s strategic calculus appears to be shifting. There is now a growing perception in New Delhi that, under the interim leadership of Muhammad Yunus, Bangladesh may be recalibrating its foreign policy, moving away from the overt closeness seen under former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. Under Hasina, India and Bangladesh enjoyed unusually warm ties characterised by deep security cooperation, cross-border connectivity projects and shared regional objectives. Dhaka took strong action against anti-India insurgents, gave India access to transit routes through Bangladeshi territory and generally aligned itself with New Delhi’s strategic priorities.

Whether real or perceived, this shift is influencing how India reads the regional landscape.

Chauhan also drew attention to a broader, troubling pattern: External powers – chiefly China – are leveraging economic fragilities across the Indian Ocean region to deepen their influence. With countries such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan increasingly beholden to Chinese investment and aid, concerns are mounting that Beijing is systematically encircling India through soft-power entrenchment.

Bangladesh’s case, however, remains somewhat unique. Its economy, though under pressure, is relatively resilient, and Dhaka continues to emphasise pragmatic, interest-driven diplomacy over ideological alignment. The Kunming meeting, while symbolically charged, does not yet represent a formal strategic realignment.

Still, the formation of a trilateral framework marks a significant development. Unlike previous bilateral engagements, this format introduces a new dimension of coordination that could evolve in unpredictable ways.

The echoes of history are hard to ignore. In the 1960s, China and Pakistan maintained a tight strategic axis that tacitly encompassed East Pakistan – what is now Bangladesh. That configuration unravelled in 1971 with Bangladesh’s independence.

Today, however, subtle signs suggest elements of that strategic triad may be resurfacing – this time in a more complex geopolitical theatre.

For Beijing, deepening ties with both Pakistan and Bangladesh serves its broader objective of consolidating influence in South Asia and the Indian Ocean region. For Islamabad, it provides a layer of diplomatic insulation and strategic leverage. For Dhaka, the relationship is more tactical – an attempt to hedge against regional volatility at a time when its once-stable ties with New Delhi appear increasingly uncertain.

Bangladesh’s cautious posture is also shaped by volatile domestic politics. Since the July protests and the installation of an interim administration, internal cohesion has frayed. Polarisation is resurging, and with national elections looming in early 2026, the government’s priority is stability, not strategy. Foreign policy in this climate is reactive – not transformative.

Dhaka understands the risks of leaning too far in any direction. Lingering historical resentments with Pakistan remain politically sensitive while an overreliance on China would strain crucial trade and diplomatic ties with the West, especially the United States, where concerns over democratic backsliding and human rights have sharpened.

In this context, any overt strategic alignment could invite unnecessary scrutiny and backlash.

The Kunming meeting, despite its symbolism, was primarily economic in focus – touching on trade, connectivity, infrastructure and cultural cooperation. However, when China and Pakistan floated the proposal to institutionalise trilateral cooperation through a joint working group, Bangladesh demurred. This was not indecision. It was a deliberate, calculated refusal.

Dhaka’s foreign policy has long been defined by “engagement without entanglement”. It maintains open channels with all major powers while avoiding the traps of bloc politics. This nonaligned posture is a core principle guiding its diplomacy. Bangladesh welcomes dialogue and economic cooperation, but it draws a firm line at military or strategic alignment.

For India, interpreting Bangladesh’s moves requires nuance. While Dhaka continues to broaden its international partnerships, it has not abandoned its critical role in India’s security calculus, particularly in the northeastern region. The challenge for New Delhi is not just to monitor emerging partnerships but to reinforce the value of its own.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s, security cooperation between New Delhi and Dhaka under Hasina’s Awami League was pivotal in stabilising the border region. Bangladesh’s decisive crackdown on militant groups, coupled with close coordination with Indian intelligence and security agencies, played a crucial role in suppressing insurgent threats.

Today, with India’s ties to both China and Pakistan under severe strain, any perceived shift in Dhaka’s stance is scrutinised intensely in New Delhi. The fear that Beijing and Islamabad might exploit Bangladesh as a strategic lever to apply asymmetric pressure remains deeply ingrained in India’s security mindset.

Yet, Bangladesh’s explicit rejection of the proposed trilateral working group reveals a clear-eyed understanding of these sensitivities. It underscores Dhaka’s intent to steer clear of actions that could escalate regional tensions.

This evolving dynamic poses a dual challenge for India: It demands a recalibrated response that moves beyond reactive defensiveness. New Delhi must embrace a more sophisticated, forward-looking strategy – one that transcends old political loyalties and adapts to the shifting diplomatic contours of South Asia.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.

Interim leader Yunus says Awami League members committed ‘heinous act’ in attempt to disrupt rally of student-led NCP.

Bangladeshi security forces clashed with supporters of deposed Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, leaving at least three people dead and many injured.

Violence broke out Wednesday in the southern town of Gopalganj when members of Hasina’s Awami League tried to disrupt a rally by the National Citizens Party (NCP), which is made up of students who spearheaded the unrest that toppled the leader last year.

TV footage showed pro-Hasina activists armed with sticks attacking police and setting vehicles on fire as NCP leaders arrived at the new party’s “March to Rebuild the Nation” programme commemorating the uprising.

Monoj Baral, a nurse at the Gopalganj District Hospital, told the news agency AFP that three people were killed. Local media, including the English-language Daily Star, said that four had died.

One of the dead was identified by Baral as Ramjan Sikdar. The other two were taken away from the hospital by their families, said Baral.

Authorities imposed an overnight curfew in the district.

Bangladesh’s interim leader Muhammad Yunus, who replaced Hasina three days after her overthrow last year, said that the attempt by the former leader’s supporters to foil the NCP rally was “a shameful violation of their fundamental rights”.

“This heinous act … will not go unpunished,” said a statement from the Nobel Peace Prize laureate’s office.

Hasnat Abdullah, an NCP coordinator, said rally attendees took refuge at a police station after being attacked. “We don’t feel safe at all. They threatened to burn us alive,” he told AFP.

Bangladesh has been in political turmoil since Hasina was toppled nearly a year ago.

Hasina, who fled to India following a student-led uprising last August, faces several charges. This month, she was sentenced in absentia to six months in prison for contempt of court by the country’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT).

Gopalganj is a politically sensitive district because the mausoleum of Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, is located there.

Rahman, the country’s founding president, was buried there after he was assassinated along with most of his family members in a military coup in 1971.

Hasina would go on to contest elections from the constituency.

The NCP march was launched on July 1 across all districts in Bangladesh as part of its drive to position itself as a new force in Bangladeshi politics.

The country’s political landscape has been largely dominated by two dynastic families: Hasina’s Awami League party and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia.

Yunus has said an election will be held in April next year.

The US and other Western countries have been reducing their funding, prioritising their defence spending instead.

The plight of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh could rapidly deteriorate further unless more funding can be secured for critical assistance services, according to the United Nations refugee agency.

Bangladesh has registered its biggest influx of Myanmar’s largest Muslim minority over the past 18 months since a mass exodus from an orchestrated campaign of death, rape and persecution nearly a decade ago by Myanmar’s military.

“There is a huge gap in terms of what we need and what resources are available. These funding gaps will affect the daily living of Rohingya refugees as they depend on humanitarian support on a daily basis for food, health and education,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) spokesperson Babar Baloch told reporters in Geneva on Friday.

The humanitarian sector has been roiled by funding reductions from major donors, led by the United States under President Donald Trump and other Western countries, as they prioritise defence spending prompted by growing concerns over Russia and China.

Baloch added: “With the acute global funding crisis, the critical needs of both newly arrived refugees and those already present will be unmet, and essential services for the whole Rohingya refugee population are at risk of collapsing unless additional funds are secured.”

If not enough funding is secured, health services will be severely disrupted by September, and by December, essential food assistance will stop, said the UNHCR, which says that its appeal for $255m has only been 35 percent funded.

In March, the World Food Programme announced that “severe funding shortfalls” for Rohingya were forcing a cut in monthly food vouchers from $12.50 to $6 per person.

More than one million Rohingya have been crammed into camps in southeastern Bangladesh, the world’s largest refugee settlement. Most fled the brutal crackdown in 2017 by Myanmar’s military, although some have been there for longer.

These camps cover an area of just 24 square kilometres (nine square miles) and have become “one of the world’s most densely populated places”, said Baloch.

Continued violence and persecution against the Rohingya, a mostly Muslim minority in mainly Buddhist Myanmar’s western Rakhine state, have kept forcing thousands to seek protection across the border in Bangladesh, according to the UNHCR. At least 150,000 Rohingya refugees have arrived in Cox’s Bazar in southeast Bangladesh over the past 18 months.

The Rohingya refugees also face institutionalised discrimination in Myanmar and most are denied citizenship.

“Targeted violence and persecution in Rakhine State and the ongoing conflict in Myanmar have continued to force thousands of Rohingya to seek protection in Bangladesh,” said Baloch. “This movement of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh, spread over months, is the largest from Myanmar since 2017, when some 750,000 fled the deadly violence in their native Rakhine State.”

Baloch also hailed Muslim-majority Bangladesh for generously hosting Rohingya refugees for generations.

Dhaka, Bangladesh — On July 16, 2024, as security forces launched a brutal crackdown on student protesters campaigning against then-Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s increasingly authoritarian government, Bangladeshi rapper Muhammad Shezan released a song.

Titled Kotha Ko (speak up in Bangla), the song asked: “The country says it’s free, then where’s your roar?”

It was the day that Abu Sayed, a protester, was killed, becoming the face of the campaign to depose Hasina after 15 years in power. Sayed’s death fuelled the public anger that led to intensified protests. And Shezan’s Kotha Ko, along with a song by another rapper, Hannan Hossain Shimul, became anthems for that movement, culminating in Hasina fleeing Bangladesh for India in August.

Fast forward a year, and Shezan recently released another hit rap track. In Huddai Hutashe, he raps about how “thieves” are being garlanded with flowers – a reference, he said, to unqualified individuals seizing important positions in post-Hasina Bangladesh.

As the country marks the anniversary of the uprising against Hasina, protest tools that played a key role in galvanising support against the former leader have become part of mainstream Bangladeshi politics.

Rap, social media memes and graffiti are now also a part of the arsenal of young Bangladeshis looking to hold their new rulers accountable, just as they once helped uproot Hasina.

![A social media meme mocking the Bangladesh government logo, by showing a mob beating a person, highlighting the law and order chaos that followed Hasina's ouster [Masum Billah/Al Jazeera]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/10-1752214367.jpg)

As mob violence surged in Bangladesh last autumn in the aftermath of Hasina’s ouster, a Facebook meme went viral.

It showed the familiar red and green seal of the Bangladesh government. But instead of the golden map of the nation inside the red circle, it depicted stick-wielding men beating a fallen victim.

The text around the emblem had been tweaked – in Bangla, it no longer read “People’s Republic of Bangladesh Government,” but “Mob’s Republic of Bangladesh Government”.

The satire was biting and pointed, revealing an uncomfortable side of post-Hasina Bangladesh. “It was out of this frustration that I created the illustration, as a critique on the ‘rule of mobs’ and the government’s apparent inaction,” said Imran Hossain, a journalist and activist who created the meme. “Many people shared it on social media, and some even used it as their profile picture as a quiet form of protest.”

After the student-led revolution, the newly appointed interim government under Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus embarked on a sweeping reform agenda – covering the constitution, elections, judiciary and police.

But mob violence emerged as a challenge that the government struggled to contain. This period saw mobs attacking Sufi shrines and Hindu minorities, storming women’s football pitches, and even killing alleged drug dealers – many of these incidents filmed, shared and fiercely debated online.

“After the July uprising, some groups in Bangladesh – many of whom had been oppressed under the previous regime – suddenly found themselves with a lot of power. But instead of using that newfound power responsibly, some began taking the law into their own hands,” Hossain said.

As with rap songs, such memes had also played a vital role in capturing the public mood during the anti-Hasina protests.

After security officials killed hundreds of protesters on July 18 and 19, Sheikh Hasina was seen crying over damage to a metro station allegedly caused by demonstrators. That moment fuelled a wave of memes.

One viral meme said “Natok Kom Koro Prio” (Do less drama, dear), and was viral throughout the latter half of July. It mocked Hasina’s sentimental display – whether over the damaged metro station or her claim to “understand the pain of losing loved ones” after law enforcement agencies had killed hundreds.

Until then, ridiculing Sheikh Hasina had been a “difficult” act, said Punny Kabir, a prominent social media activist known for her witty political memes over the years, and a PhD student at the University of Cologne.

While newspaper cartoonists previously used to lampoon political leaders, that stopped during Hasina’s rule since 2009, which was marked by arrests of critics and forced disappearances, she said.

“To face off an authoritarian regime, it’s [ridiculing] an important and powerful tool to overcome fear and surveillance,” Kabir said. “We made it possible, and it broke the fear.”

![Protesters on Dhaka streets on August 2, 2024 [Masum Billah/Al Jazeera]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/3-1752214625.jpg)

As fear of Sheikh Hasina faded from social media, more people found their voice – a reflection that soon spread onto the streets. Thousands of walls were covered with paintings, graffiti, and slogans of courage such as “Killer Hasina”, “Stop Genocide” and “Time’s Up Hasina”.

“These artworks played a big role in the protests,” said political analyst and researcher Altaf Parvez. “Slogans like ‘If you are scared, you’re finished; but if you resist, you are Bangladesh’ – one slogan can make all the difference, and that’s exactly what happened.

“People were searching for something courageous. When someone created something that defied fear – creative slogans, graffiti, cartoons – these became sources of inspiration, spreading like wildfire. People found their voice through them,” he added.

That voice did not go silent with Hasina’s departure.

Today, memes targeting various political parties, not just the government, are widespread.

One of Imran’s works uses a Simpsons cartoon to illustrate how sycophants used to eulogise Hasina’s family for its role in Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation war when she was in power. Now, the cartoon points out, loyalists of the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)’s leader Khaleda Zia and her son Tarique Rahman are trying to flatter their family for their contribution to the country’s independence movement. Hasina’s father, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, led the freedom struggle, while Zia’s husband Ziaur Rahman was a senior army officer who announced the country’s independence on March 27, 1971.

Another meme from a popular Gen-Z Facebook page called WittiGenZ recently highlighted allegations of sexual misconduct by a leader of the National Citizen Party (NCP) – a party formed by Bangladesh’s students.

![Protesters drawing graffiti, writing slogans against Sheikh Hasina on the walls of Dhaka [Masum Billah/Al Jazeera]](https://www.occasionaldigest.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/6-1752214764.jpg)

Political analysts in Bangladesh believe the tools that contributed to toppling Sheikh Hasina will continue to be relevant in the country’s future.

“Memes and photo cards in Bangladesh essentially do what X does in the West. They provide the most effective short-form political commentary to maximise virality,” said US-based Bangladeshi geopolitical columnist Shafquat Rabbee.

Bangladesh’s central bank unveiled new banknote designs inspired by the graffiti created by students during last July’s monsoon uprising, a nod to the art form’s widespread popularity as a means of political communication.

And rap, Rabbee said, found a natural entry in Bangladeshi politics in 2024. In Bangladesh’s context, back in July 2024, political street fighting became a dominant and fitting instrument of protest against Hasina’s repressive forces, he said.

The artists behind the songs say they never expected their work to echo across Bangladesh.

“I wrote these lyrics myself,” Shezan said, about Kotha Ko. “I didn’t think about how people would respond – we simply acted out of a sense of responsibility to what was happening.”

As with Shezan’s song, fellow rapper Hannan’s Awaaz Utha also went viral online, especially on Facebook, the same day – July 18 – that it was released. “You hit one, 10 more will come back,” a line said. As Hasina found it, they did.

The rappers themselves also joined the protests. Hannan was arrested a week after his song’s release and was only freed after Hasina resigned and fled to India.

But now, said Shezan, rap was there to stay in Bangladesh’s public life, from advertising jingles to lifestyle. “Many people are consciously or subconsciously embracing hip-hop culture,” he said.

“The future of rap is bright.”

Deposed prime minister and others are indicted for crimes against humanity, with trial set for August.

Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) has indicted former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and two senior officials over alleged crimes against humanity linked to a deadly crackdown on protesters during last year’s July uprising.

The tribunal, led by Justice Golam Mortuza Mozumder and comprising justices Shafiul Alam Masud and Mohitul Enam Chowdhury, formally charged Hasina on Thursday.

Proceedings will begin on August 3 with opening statements, followed by the first witness testimony.

Hasina, who fled to India following a student-led uprising last August, had been facing several charges. Earlier this month, in a separate ruling, she was sentenced to six months in prison for contempt of court by the ICT. That had marked the first time she had received a formal sentence in any of the cases.

Chief Prosecutor Muhammad Tajul Islam said that the sentence delivered in absentia will take effect if Hasina is arrested or voluntarily returns to Bangladesh.

The two other accused on Thursday are former home minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal and former police chief Chowdhury Abdullah al-Mamun. While al-Mamun appeared before the court and remains in custody, both Hasina and Kamal have fled abroad.

The charges stem from Hasina’s now ousted government’s violent response to mass demonstrations, which critics say resulted in widespread human rights abuses and hundreds of deaths.

Hasina, who now lives in self-imposed exile in India after being deposed following a 15-year rule, has dismissed the tribunal as politically motivated.

Joypurhat/Dhaka, Bangladesh, and New Delhi/Kolkata, India – Under the mild afternoon sun, 45-year-old Safiruddin sits outside his incomplete brick-walled house in Baiguni village of Kalai Upazila in Bangladesh, nursing a dull ache in his side.

In the summer of 2024, he sold his kidney in India for 3.5 lakh taka ($2,900), hoping to lift his family out of poverty and build a house for his three children – two daughters, aged five and seven, and an older 10-year-old son. That money is long gone, the house remains unfinished, and the pain in his body is a constant reminder of the price he paid.

He now toils as a daily labourer in a cold storage facility, as his health deteriorates – the constant pain and fatigue make it hard for him to carry out even routine tasks.

“I gave my kidney so my family could have a better life. I did everything for my wife and children,” he said.

At the time, it didn’t seem like a dangerous choice. The brokers who approached him made it sound simple – an opportunity rather than a risk. He was sceptical initially, but desperation eventually won over his doubts.

The brokers took him to India on a medical visa, with all arrangements – flights, documents, and hospital formalities – handled entirely by them. Once in India, although he travelled on his original Bangladeshi passport, other documents, such as certificates falsely showing a familial relationship with the intended recipient of his kidney, were forged.

His identity was altered, and his kidney was transplanted into an unknown recipient whom he had never met. “I don’t know who got my kidney. They [the brokers] didn’t tell me anything,” Safiruddin said.

By law, organ donations in India are only permitted between close relatives or with special government approval, but traffickers manipulate everything – family trees, hospital records, even DNA tests – to bypass regulations.

“Typically, the seller’s name is changed, and a notary certificate – stamped by a lawyer – is produced to falsely establish a familial relationship with the recipient. Forged national IDs support the claim, making it appear as though the donor is a relative, such as a sister, daughter, or another family member, donating an organ out of compassion,” said Monir Moniruzzaman, a Michigan State University professor and a member of the World Health Organization’s Task Force on Organ Transplantation, who is researching organ trafficking in South Asia.

Safiruddin’s story isn’t unique. Kidney donations are so common in his village of Baiguni, that locals know the community of less than 6,000 people as the “village of one kidney”. The Kalai Upazila region that Baiguni belongs to is the hotspot for the kidney trade industry: A 2023 study published in the British Medical Journal Global Health publication estimated one in 35 adults in the region has sold a kidney.

Kalai Upazila is one of Bangladesh’s poorest regions. Most donors are men in their early 30s lured by the promise of quick money. According to the study, 83 percent of those surveyed cited poverty as the main reason for selling a kidney, while others pointed to loan repayments, drug addiction or gambling.

Safiruddin said that the brokers – who had taken his passport – never returned it. He didn’t even get the medicines he had been prescribed after the surgery. “They [the brokers] took everything.”

Brokers often confiscate passports and medical prescriptions after the surgery, erasing any trail of the transplant and leaving donors without proof of the procedure or access to follow-up care.

The kidneys are sold to wealthy recipients in Bangladesh or India, many of whom seek to bypass long wait times and the strict regulations of legal transplants. In India, for example, only about 13,600 kidney transplants were performed in 2023 – compared with an estimated 200,000 patients who develop end-stage kidney disease annually.

Al Jazeera spoke with more than a dozen kidney donors in Bangladesh, all of whom shared similar stories of being driven to sell their kidneys due to financial hardship. The trade is driven by a simple yet brutal equation: Poverty creates the supply, while long wait times, a massive shortage of legal donors, the willingness of wealthy patients to pay for quick transplants and a weak enforcement system ensure that the demand never ceases.

Josna Begum, 45, a widow from Binai village in Kalai Upazila, was struggling to raise her two daughters, 18 and 20 years old, after her husband died in 2012. She moved to Dhaka to work in a garment factory, where she met and married another man named Belal.

After their marriage, both Belal and Josna were lured by a broker into selling their kidneys in India in 2019.

“It was a mistake,” Josna said. She explained that the brokers first promised her five lakh taka (about $4,100), then raised the offer to seven lakh (around $5,700) to convince her. “But after the operation, all I got was three lakh [$2,500].”

Josna said she and Belal were taken to Rabindranath Tagore International Institute of Cardiac Sciences in Kolkata, the capital of India’s West Bengal state, where they underwent surgery. “We were taken by a bus through the Benapole border into India, where we were housed in a rented apartment near the hospital.”

To secure the transplant, the brokers fabricated documents claiming that she and the recipient were blood relatives. Like Safiruddin, she doesn’t know who received her kidney.

Despite repeated attempts, officials at Rabindranath Tagore International Institute of Cardiac Sciences have not responded to Al Jazeera’s request to comment on the case. Kolkata police have previously accused other brokers of facilitating illegal kidney transplants at the same hospital in 2017.

Josna said her passport and identification documents were handled entirely by the brokers. “I was OK with them taking away the prescriptions. But I asked for my passport. They never gave it back,” she said.

She stayed in India for nearly two months before returning to Bangladesh – escorted by the brokers who had her passport, and still held out the promise of paying her what they had committed to.

The brokers had also promised support for her family and even jobs for her children, but after the initial payment and a few token payments on Eid, they cut off contact.

Soon after he was paid – also three lakh taka ($2,500) – for his transplant, Belal abandoned Josna, later marrying another woman. “My life was ruined,” she said.

Josna now suffers from chronic pain and struggles to afford medicines. “I can’t do any heavy work,” she said. “I have to survive, but I need medicine all the time.”

In some cases, victims have become perpetrators of the kidney scam, too.

Mohammad Sajal (name changed), was once a businessman in Dhaka selling household items like pressure cookers, plastic containers and blenders through Evaly, a flashy e-commerce platform that promised big returns. But when Evaly collapsed following a 2021 scam, so did his savings – and his livelihood.

Drowning in debt and under immense pressure to repay what he owed, he sold his kidney in 2022 at Venkateshwar Hospital in Delhi. But the promised 10 lakh taka ($8,200) never materialised. He received only 3.5 lakh taka ($2,900).

“They [the brokers] cheated me,” Sajal said. Venkateshwar Hospital has not responded to repeated requests from Al Jazeera for comment on the case.

There was only one way he could earn what he had thought he would get for his kidney, Sajal concluded at the time: by joining the brokers to dupe others. For months, he worked as a broker, arranging kidney transplants for several Bangladeshi donors in Indian hospitals. But after a financial dispute with his handlers, he left the trade, fearing for his life.

“I am now in front of this gang’s gun,” he said. The network he left behind operates with impunity, he said, stretching from Bangladeshi hospitals to the Indian medical system. “Everyone from the doctors to recipients to the brokers on both sides of borders are involved,” he said.

Now, Sajal works as a ride-share driver in Dhaka, trying to escape the past. But the scars, both physical and emotional, remain. “No one willingly gives a kidney out of hobby or desire,” he said. “It is a simple calculation: desperation leads to this.”

Acknowledging the cross-border kidney trafficking trade, Bangladesh police say they are cracking down on those involved. Assistant Inspector General Enamul Haque Sagor of Bangladesh Police said that, in addition to uniformed officers, undercover investigators have been deployed to track organ trafficking networks and gather intelligence.

“This issue is under our watch, and we are taking action as required,” he said.

Sagor said that police have arrested multiple individuals linked to organ trafficking syndicates, including brokers. “Many people get drawn into kidney sales through these networks, and we are working to catch them,” he added.

Across the border, Indian law enforcement agencies, too, have cracked down on some medical professionals accused of involvement in kidney trafficking. In July 2024, the Delhi Police arrested Dr Vijaya Rajakumari, a 50-year-old kidney transplant surgeon associated with a Delhi hospital. Investigations revealed that between 2021 and 2023, Dr Rajakumari performed approximately 15 transplant surgeries on Bangladeshi patients at a private hospital, Indian officials said.

But experts say that these arrests are too sporadic to seriously dent the business model that underpins the kidney trade.

And experts say Indian authorities face competing pressures – upholding the law, but also promoting medical tourism, a sector that was worth $7.6bn in 2024. “Instead of enforcing ethical standards, the focus is on the economic advantages of the industry, allowing illegal transplants to continue,” said Moniruzzaman.

In India, the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (THOA) of 1994 regulates organ donations, permitting kidney transplants primarily between close relatives such as parents, siblings, children and spouses to prevent commercial exploitation. When the donor is not a near relative, the case must receive approval from a government-appointed body known as an authorisation committee to ensure the donation is altruistic and not financially motivated.

However, brokers involved in kidney trafficking circumvent these regulations by forging documents to establish fictitious familial relationships between donors and recipients. These fraudulent documents are then submitted to authorisation committees, which – far too often, say experts – approve the transplants.

Experts say the foundation of this illicit system lies in the ease with which brokers manipulate legal loopholes. “They fabricate national IDs and notary certificates to create fictitious family ties between donors and recipients. These papers can be made quickly and cheaply,” said Moniruzzaman.

With these falsified identities, transplants are performed under the pretence of legal donations between relatives.

In Dhaka, Shah Muhammad Tanvir Monsur, director general (consular) at Bangladesh’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said that the country’s government officials had no role in the document fraud, and that they “duly followed” all legal procedures. He also denied any exchange of information between India and Bangladesh on cracking down on cross-border kidney trafficking.

Over in India, Amit Goel, deputy commissioner of police in Delhi, who has investigated several cases of kidney trafficking in the city, including that of Rajakumari, the doctor, said that hospital authorities often struggle to detect forged documents, allowing illegal transplants to proceed.

“In the cases I investigated, I found that the authorisation board approved those cases because they couldn’t identify the fake documents,” he said.

But Moniruzzaman pointed out that Indian hospitals also have a financial incentive to overlook discrepancies in documents.

“Hospitals turn a blind eye because organ donation [in general] is legal,” Moniruzzaman said. “More transplants mean more revenue. Even when cases of fraud surface, hospitals deny responsibility, insisting that documentation appears legitimate. This pattern allows the trade to continue unchecked,” he added.

Mizanur Rahman, a broker who operates across multiple districts in Bangladesh, said that traffickers often target individual doctors or members of hospital review committees, offering bribes to facilitate these transplants. “Usually, brokers in Bangladesh are in touch with their counterparts in India who set up these doctors for them,” Rahman told Al Jazeera. “These doctors often take a major chunk of the money involved.”

Dr Anil Kumar, director of the National Organ and Tissue Transplant Organisation (NOTTO) – India’s central body overseeing organ donation and transplant coordination – declined to comment on allegations of systemic discrepancies that have enabled rising cases of organ trafficking.

However, a former top official from NOTTO pointed out that hospitals often are up against not just brokers and seemingly willing donors with what appear to be legitimate documents, but also wealthier recipients. “If the hospital board is not convinced, recipients often take the matter to higher authorities or challenge the decision in court. So they [hospitals] also want to avoid legal hassles and proceed with transplants,” this official said, speaking on condition of anonymity.

Meanwhile, organ trafficking networks continue to adapt their strategies. When police or official scrutiny increases in one location, the trade simply moves elsewhere. “There is no single fixed hospital; the locations keep changing,” Moniruzzaman said. “When police conduct a raid, the hospital stops performing transplants.

“Brokers and their network – Bangladeshi and Indian brokers working together – coordinate to select new hospitals at different times.”

For brokers and hospitals that are involved, there is big money at stake. Recipients often pay between $22,000 and $26,000 for a kidney.

But donors get only a tiny fraction of this money. “The donors get three to five lakh taka [$2,500 to $4,000] usually,” said Mizanur Rahman, the broker. “The rest of the money is shared with brokers, officials who forge documents, and doctors if they are involved. Some money is also spent on donors while they live in India.”

In some cases, the deception runs even deeper: traffickers lure Bangladeshi nationals with promises of well-paying jobs in India, only to coerce them into kidney donations.

Victims, often desperate for work, are taken to hospitals under false pretences, where they undergo surgery without fully understanding the consequences. In September last year, for instance, a network of traffickers in India held many Bangladeshi job seekers captive, either forced or deceived them into organ transplants, and abandoned them with minimal compensation. Last year, police in Bangladesh arrested three traffickers in Dhaka who smuggled at least 10 people to New Delhi under the guise of employment, only to have them forced into kidney transplants.

“Some people knowingly sell their kidneys due to extreme poverty, but a significant number are deceived,” said Shariful Hasan, associate director of the Migration Programme at BRAC, formerly the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, one of the world’s largest nongovernmental development organisations. “A rich patient in India needs a kidney, a middleman either finds a poor Bangladeshi donor or lures someone in the name of employment, and the cycle continues.”

Vasundhara Raghavan, CEO of the Kidney Warriors Foundation, a support group in India for patients with kidney diseases, said that a shortage of legal donors was a “major challenge” that drove the demand for trafficked organs.

“Desperate patients turn to illicit means, fuelling a system that preys on the poor.”

She acknowledged that India’s legal framework was aimed at preventing organ transplants from turning into an exploitative industry. But in reality, she said, the law had only pushed organ trade underground.

“If organ trade cannot be entirely eliminated, a more systematic and regulated approach should be considered. This could involve ensuring that donors undergo mandatory health screenings, receive postoperative medical support for a fixed period, and are provided with financial security for their future wellbeing,” Raghavan said.

Back in Kalai Upazila, Safiruddin nowadays spends most of his time at home, his movements slower, his strength visibly diminished. “I am not able to work properly,” he said.

He says there are nights when he lies awake, thinking of the promises the brokers made, and the dreams they shattered. He doesn’t know when, and if, he will be able to complete the construction of his house. He thought the surgery would bring his family a pot of cash to build a future. Instead, his children have been left with an ailing father – and he with a sense of betrayal that Safiruddin can’t shake off. “They took my kidney and vanished,” he said.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from Journalists for Transparency.