‘End is near’: Will Kabul become first big city without water by 2030? | Water

Kabul, a city of over six million people, could become the first modern city to run out of water in the next five years, a new report has warned.

Groundwater levels in the Afghan capital have dropped drastically due to over-extraction and the effects of climate change, according to a report published by nonprofit Mercy Corps.

So, is Kabul’s water crisis at a tipping point and do Afghan authorities have the resources and expertise to address the issue?

The depth of the crisis

Kabul’s aquifer levels have plummeted 25-30 metres (82 – 98 feet) in the past decade, with extraction of water exceeding natural recharge by a staggering 44 million cubic metres (1,553cu feet) a year, the report, published in April this year, noted.

If the current trend continues, Kabul’s aquifers will become dry by 2030, posing an existential threat to the Afghan capital, according to the report. This could cause the displacement of some three million Afghan residents, it said.

The report said UNICEF projected that nearly half of Kabul’s underground bore wells, the primary source of drinking water for residents, are already dry.

It also highlights widespread water contamination: Up to 80 percent of groundwater is believed to be unsafe, with high levels of sewage, arsenic and salinity.

Conflict, climate change and government failures

Experts point to a combination of factors behind the crisis: climate change, governance failures and increasing pressures on existing resources as the city’s population has expanded from less than one million in 2001 to roughly six million people today.

Two decades of US-led military intervention in Afghanistan also played a role in the crisis, as it forced more people to move to Kabul while governance in the rest of the country suffered.

“The prediction is based on the growing gap between groundwater recharge and annual water extraction. These trends have been consistently observed over recent years, making the forecast credible,” said Assem Mayar, water resource management expert and former lecturer at Kabul Polytechnic University.

“It reflects a worst-case scenario that could materialise by 2030 if no effective interventions are made,” he added.

Najibullah Sadid, senior researcher and a member of the Afghanistan Water and Environment Professionals Network, said it was impossible to put a timeline on when the capital city would run dry. But he conceded that Kabul’s water problems are grave.

“Nobody can claim when the last well will run dry, but what we know is that as the groundwater levels further drop, the capacity of deep aquifers become less – imagine the groundwater as a bowl with depleting water,” he said.

“We know the end is near,” he said.

A vast portion of the Afghan capital relies on underground borewells, and as water levels drop, people dig deeper or in different locations looking for sources of water.

According to an August 2024 report by the National Statistics Directorate, there are approximately 310,000 drilled wells across the country. According to the Mercy Corps report, it is estimated that there are also nearly 120,000 unregulated bore wells across Kabul.

A 2023 UN report found that nearly 49 percent of borewells in Kabul are dry, while others are functioning at only 60 percent efficiency.

The water crisis, Mayar said, exposes the divide between the city’s rich and poor. “Wealthier residents can afford to drill deeper boreholes, further limiting access for the poorest,” he said. “The crisis affects the poorest first.”

The signs of this divide are evident in longer lines outside public water taps or private water takers, says Abdulhadi Achakzai, director at the Environmental Protection Trainings and Development Organization (EPTDO), a Kabul-based climate protection NGO.

Poorer residents, often children, are forced to continually search for sources of water.

“Every evening, even late at night, when I am returning home from work, I see young children with small cans in their hands looking for water … they look hopeless, navigating life collecting water for their homes rather than studying or learning,” he said.

Additionally, Sadid said, Kabul’s already depleted water resources were being exploited by the “over 500 beverage and mineral water companies” operating in the capital city,” all of which are using Kabul’s groundwater”. Alokozay, a popular Afghan soft drinks company, alone extracts nearly one billion litres (256 million gallons) of water over a year — 2.5 million litres (660,000 gallons) a day — according to Sadid’s calculations.

Al Jazeera sent Alokozay questions about its water extraction on June 21, but has yet to receive a response.

Kabul, Sadid said, also had more than 400 hectares (9,884 acres) of green houses to grow vegetables, which suck up 4 billion litres (1.05 billion gallons) of water every year, according to his calculations. “The list [of entities using Kabul water] is long,” he said.

‘Repeated droughts, early snowmelt and reduced snowfall’

The water shortage is further compounded by climate change. Recent years have seen a significant reduction in precipitation across the country.

“The three rivers — Kabul river, Paghman river and Logar river—that replenish Kabul’s groundwater rely heavily on snow and glacier meltwater from the Hindu Kush mountains,” the Mercy Corps report noted. “However, between October 2023 to January 2024, Afghanistan only received only 45 to 60 percent of the average precipitation during the peak winter season compared to previous years.”

Mayar, the former lecturer at Kabul Polytechnic University, said that while it was difficult to quantify exactly how much of the crisis was caused by climate change, extreme weather events had only added to Kabul’s woes.

“Climate-related events such as repeated droughts, early snowmelts, and reduced snowfall have clearly diminished groundwater recharge opportunities,” he said.

Additionally, increased air temperature has led to greater evaporation, raising agricultural water consumption, said Sadid from the Afghanistan Water and Environment Professionals Network.

While several provinces have experienced water scarcity, particularly within agrarian communities, Kabul remains the worst affected due to its growing population.

Decades of conflict

Sadid argued Kabul’s crisis runs deeper than the impact of climate change, compounded by years of war, weak governance, and sanctions on the aid-dependent country.

Much of the funds channelled into the country were diverted to security for the first two decades of the century. Since the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, funding has been used to tackle an escalating humanitarian crisis. Western sanctions have also significantly stymied development projects that could have helped Kabul better manage the current water crisis.

As a result, authorities have struggled with the maintenance of pipelines, canals and dams — including basic tasks like de-sedimentation.

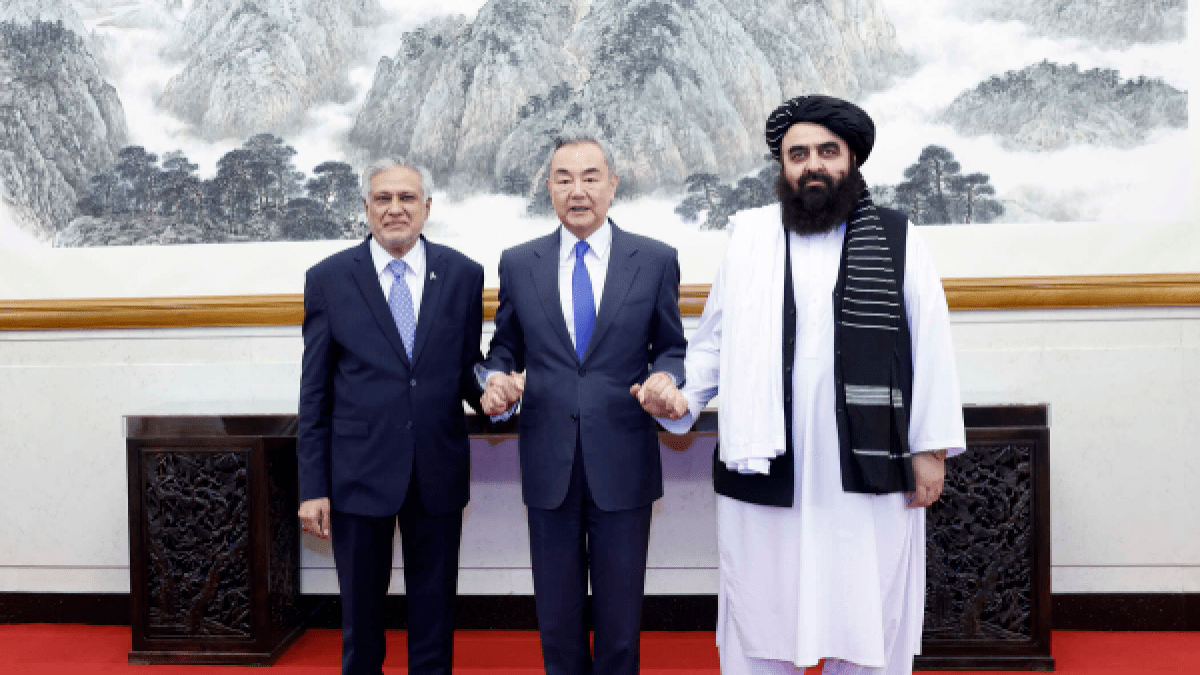

“The crisis is already beyond the capacity of the current de facto authorities,” Mayar said, referring to the Taliban. “In well-managed cities, such impacts are mitigated through robust water governance and infrastructure. Kabul lacks such capacity, and the current authorities are unable to address the problem without external support,” he added.

As a result, environmental resilience projects have taken a backseat.

“Several planned initiatives, including projects for artificial groundwater recharge, were suspended following the Taliban takeover,” Mayar pointed out. “Sanctions continue to restrict organisations and donors from funding and implementing essential water-related projects in Afghanistan,” he said.

Sadid pointed out one example: An Awater supply project -funded by the German Development bank KfW, along with European agencies – could have supplied 44 billion litres (11 billion gallons) of water annually to parts of Kabul from Logar aquifers.

“But currently this project has been suspended,” he said, even though two-thirds of the initiative was already completed when the government of former President Ashraf Ghani collapsed in 2021.

Similarly, India and the Ghani government had signed an agreement in 2021 for the construction of the Shah-toot dam on the Kabul River. Once completed, the dam could supply water to large parts of Kabul, Sadid said, “but its fate is uncertain now.”

What can be done to address the water crisis?

Experts recommend the development of the city’s water infrastructure as the starting point to address the crisis.

“Artificial groundwater recharge and the development of basic water infrastructure around the city are urgently needed. Once these foundations are in place, a citywide water supply network can gradually be developed,” Mayar recommended.

Achakzai agreed that building infrastructure and its maintenance were key elements of any fix.

“Aside from introducing new pipelines to the city from nearby rivers, such as in Panjshir, there needs to be an effort to recharge underground aquifers with constructions of check dams and water reservoirs,” he said, adding that these structures will also facilitate rainwater harvesting and groundwater replenishment.

“[The] Afghan government needs to renew ageing water pipes and systems. Modernising infrastructure will improve efficiency and reduce water loss,” he added.

Yet all of that is made harder by Afghanistan’s global isolation and the sanctions regime it is under, Achakzai said.

“Sanctions restrict Afghanistan’s access to essential resources, technology, and funding needed for water infrastructure development and maintenance,” he said. This, in turn, reduces agricultural productivity, and increases hunger and economic hardship, forcing communities to migrate, he warned.