Key Takeaways

- U.S. military spending accounted for nearly 40% of global military expenditures in 2023.

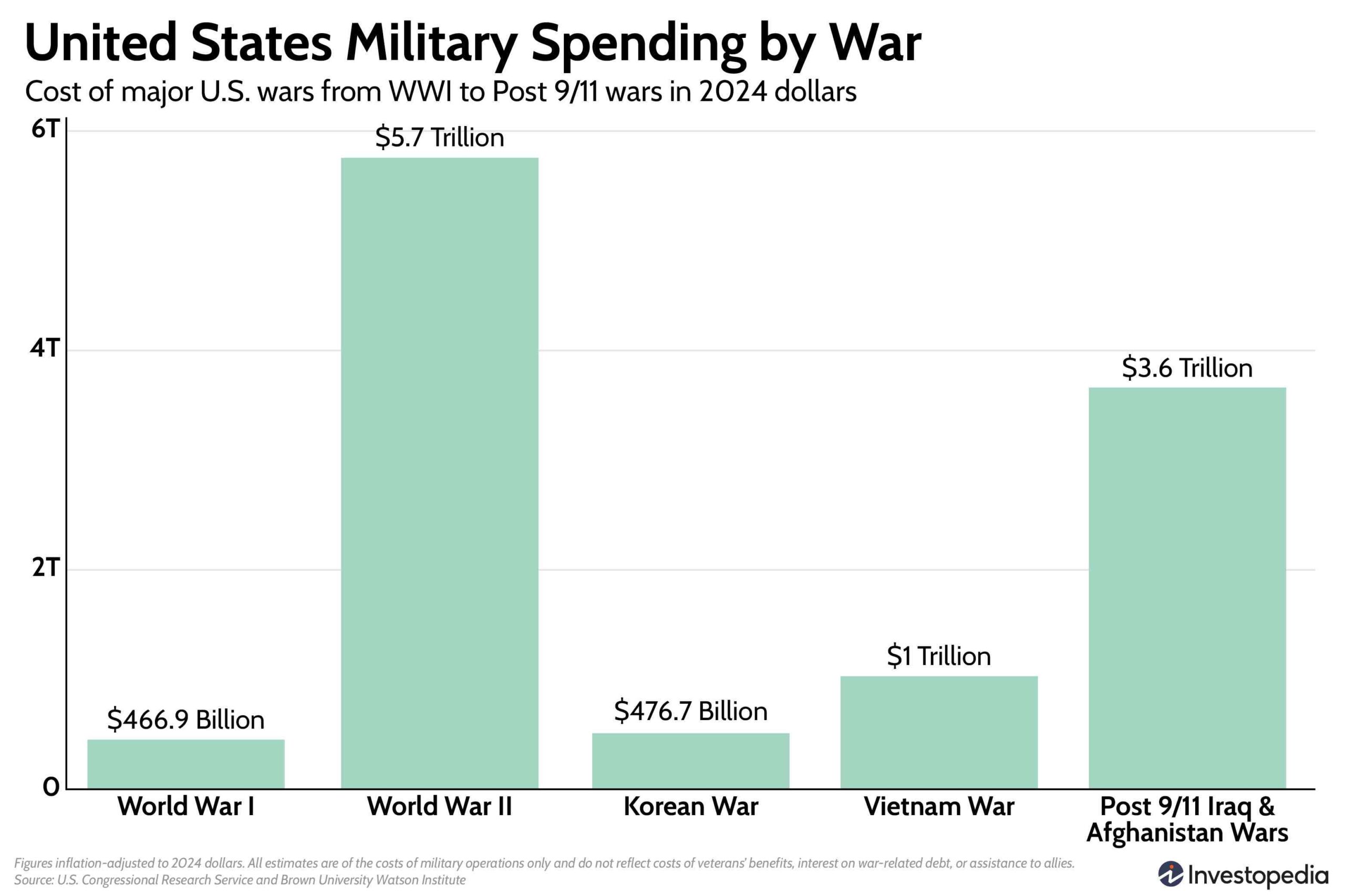

- Adjusted to 2024 dollars, WWII was the costliest U.S. war, totaling $5.74 trillion.

- Military spending as a percentage of GDP is projected to decrease in coming years.

- The DOD has requested $850 billion for 2025, representing about 3% of GDP.

- U.S. military spending is expected to increase by 10% over the next decade.

Get personalized, AI-powered answers built on 27+ years of trusted expertise.

The United States spends more on its military than any other country. Military spending by the U.S. made up almost 40% of the total military spending worldwide in 2023, according to a report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). When adjusted to 2024 dollars, the U.S. spent $5.74 trillion on WWII alone. That’s more than WWI, Vietnam, Korean, or the post-9/11 Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

U.S. military spending is expected to increase by 10% over the next decade. Congress approved and signed the Department of Defense’s (DOD) new budget into law for fiscal year 2024, which included $841.4 billion in funding for the Air Force, Navy, Army, Marine Corps, National Guard, and more.

According to projections by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), military expenditures will reach $922 billion (in 2024 dollars) by 2038. Almost 70% of that increase will be for the operation and maintenance of military personnel. The DOD requested $850 billion for 2025 to spend on the military. That’s about 3% of the GDP and relatively low compared to other times in U.S. history. The financial methods used to fund these expenditures will include increasing taxes and the national debt.

This level of military spending has national and global impacts and affects the economy.

Analyzing U.S. Military Spending from WWI to Post-9/11

Looking at military spending by war can show us how wars and defense spending affected the U.S. economy, factors that influenced military spending, and trends in defense spending over the years.

The total amount spent on each major U.S. war has been inflation-adjusted to 2024 dollars. All estimates are of the costs of military operations only and do not reflect the costs of veterans’ benefits, interest on war-related debt, or assistance to allies.

WWI (1917 – 1918): $466.91 Billion

The total cost of World War I was about $466.91 billion in 2024 dollars. When WWI began in 1914, the U.S. was in a recession. However, the economy began to recover and boom after European demand for U.S. goods increased during the war.

This only intensified when the U.S. entered WWI in 1917, causing a massive increase in federal spending due to shifting the economy from peacetime to wartime production. Entering the war also created new manufacturing jobs and left more jobs open in the labor force, as many young men were drafted into the military. The government also funded the war by increasing taxes and selling Liberty bonds to Americans, who were later paid back the value of their bonds with interest.

Funding WWI increased the U.S. national debt to over $25 billion by the war’s end. However, the U.S. emerged from WWI as an economic world power. Going into the 1920s, the national debt decreased, the government had a budget surplus, and stock market returns increased. The effect lasted until the economy crashed in 1929, the beginning of the Great Depression.

WWII (1941 – 1945): $5.74 Trillion

The U.S. spent nearly $6 trillion on World War II in 2024 dollars. In the peak year of spending, WWII expenditures made up 35.8% of the national GDP. Federal government spending on WWII was unprecedented.

The U.S. had one of the most significant periods of short-term economic growth between 1941 and 1945, largely fueled by government spending on WWII. The government-funded WWII mainly by increasing taxes and taking on debt. Government debt grew to more than $258 billion by the end of WWII. Tax rates also increased sharply, resulting in even families in poverty having to pay taxes. The average tax rate for top incomes rose up to 90% as well.

Important

To better understand how much the U.S. spent on WWII, if you spent $1 million per hour, 24 hours a day, for a year, it would take about 576 years to spend as much as the U.S. during WWII.

War-time production also boomed during this time, with over 36% of the estimated GDP solely dedicated to producing war goods. Over this short period, the U.S. produced 17 million rifles and pistols, over 80,000 tanks, 41 billion rounds of ammunition, 4 million artillery shells, 75,000 vessels, and about 300,000 planes, among other equipment and services needed for the war. However, with so many resources going into war production, it became harder for families to purchase household items like washing machines, irons, water heaters, and food that had to be rationed.

When the U.S. entered WWII, it was reeling from the effects of the Great Depression, the most severe and prolonged recession in modern world history, from 1929 to 1941. Many attribute government spending on WWII to the end of the Great Depression. However, this broken window fallacy challenges the notion that going to war is good for a nation’s economy.

The theory also suggests that a boost to one part of the economy can cause losses in another part. While WWII reduced unemployment from the Great Depression as many were enlisted or worked in factories, the standard of living declined because of rationing and high taxes. Private sector jobs and production fell, along with overall consumption and investment.

Korean War (1950 – 1953): $476.69 Billion

The U.S. spent about $476.69 billion on the Korean War in 2024 dollars. While it was technically a civil war between the two opposing sides of the Korean peninsula, the U.S. and the United Nations joined in 1950 to support South Korea in a clash over democracy versus communism.

The U.S. funded the Korean War by implementing higher tax rates, contrasting funding by debt as in WWII. To do this, the government enacted the Revenue Act of 1950, increasing income tax rates to WWII levels. Individual and corporate taxes were raised again in 1951.

This was a financially turbulent time as the government had to implement price and wage controls to respond to the inflation created by additional government spending. Consumption and investment, two key factors contributing to the GDP, slowed down during this time and did not go back to pre-war levels.

Vietnam War (1962 – 1973): $1.03 Trillion

The U.S. spent about $1 trillion on the Vietnam war between 1962 to 1973. Military operations for the Vietnam War ramped up more slowly than WWII and the Korean War, with troop deployments starting in 1965. However, the U.S. had been providing aid and military training to South Vietnam since 1954 when Vietnam split into communist North Vietnam and the democratic South.

President John F. Kennedy expanded military aid in Vietnam as the conflict escalated between the North and the South, and President Lyndon B. Johnson continued that trend after Kennedy’s assassination. Escalating U.S. involvement in Vietnam was, in part, due to fears of the domino theory—the belief that if communism took over in Vietnam, it would spread through all of Southeast Asia.

The U.S. funded the war effort mainly by increasing taxes and advancing an expansive monetary policy that eventually led to high inflation in the mid-70s. Non-military spending was also very high during this time (unlike in previous wars, where military spending was significantly higher than non-military spending), largely due to President Johnson’s Great Society social programs, which included domestic policy initiatives such as work-study, Medicare, Medicaid, increased aid to public schools, and more.

Financing the war through increasing taxes and expansionary monetary policy left a lasting effect on the economy. It fueled inflation and caused the market to stagnate, which eventually turned into stubborn stagflation.

Afghanistan and Iraq Wars (2001 – 2021): $3.68 Trillion

The U.S. spent a total of $3.68 trillion in 2024 dollars on the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars over two decades. Military spending reached record levels under President George W. Bush, who launched the war in Afghanistan and the War on Terror in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks and the Iraq War in 2003.

The Afghanistan and Iraq Wars began in weak economic conditions owing to the recession from 2001 to 2002 after the Dotcom Bubble burst. Since this was the first time in U.S. history when taxes were cut during a war, both of these wars were completely funded by deficit spending. The government used an expansionary monetary policy that included low interest rates and fewer bank regulations to help stimulate the economy, but it was unsustainable in the long term for the U.S. government’s finances. The Federal Reserve Board increased interest rates again in 2006 and 2007 to help curb the housing bubble before the Great Recession in 2008.

Military spending on operations in the Middle East peaked at nearly $964.4 billion in 2010, although it decreased in 2012 after the Budget Control Act of 2011, which was enacted in part to limit military spending to help bring down the growing national debt. However, annual caps on military spending were removed as of 2021. The Iraq War ended in 2011 under President Barack Obama, while the Afghanistan War ended in 2021 under President Joe Biden.

Key Drivers Behind U.S. Military Spending

Breakdown of U.S. Military Spending Components

Every year, the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) proposes a total budget and its specific allocations, which then go through Congress for approval.

Military spending includes many different categories. The largest category is generally operation and maintenance, including military training and planning, maintenance of equipment, and a majority of the military healthcare system. In 2023, $318 billion was spent on military operation and maintenance.

The next biggest spending category is military personnel, which goes toward pay and retirement benefits for service members. About $184 billion was spent on military personnel in 2023. Other military spending categories include acquiring weapons and systems, research and development of weapons and equipment, and smaller categories such as building military facilities and family housing.

Influences on U.S. Military Expenditure

Military spending can be influenced by several factors, such as wars, international tensions, and government expenditures. For example, military spending dropped significantly during the 1990s after the end of the Cold War before increasing again in the 2000s because of the War on Terror and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

A shift in government priorities can affect military spending. After the Budget Control Act of 2011 was passed, military spending decreased, placing annual limits on defense spending—although these limits no longer exist.

Due to the U.S.’s involvement in other countries’ economic and political landscape, humanitarian aid and development in other countries can further affect future military spending decisions.

Advancements in science and technology influence military spending, too. Developments in medical research, artificial intelligence, and new technologically advanced military systems affect defense spending. The Defense Appropriations Act for FY 2024 approved $21.43 billion in funding for science and technology, about $3.6 billion above the budget requested by the DOD. The bill also included more than $100 million over the requested amount for adopting artificial intelligence.

Economic Impact of U.S. Military Spending

The U.S. government has historically used a combination of methods to help fund wars including increasing taxes, pulling back on non-military spending, debt, and managing the money supply. All of these methods have affected the economy in various ways.

For example, WWII and the post-9/11 wars were largely funded by debt, whereas the Korean and Vietnam wars were financed by increasing taxes and inflation. One common thread between the wars, however, is that they increased pressure on inflation. Though inflation can be useful for reducing debt, the overall effects harm the economy and cause issues such as eroding purchasing power and reducing international competitiveness.

Military spending can also spur technological growth and innovation, creating demand and new jobs. However, some argue that defense spending on military research can divert talent away from other industries. High levels of military spending during WWII helped end unemployment and even increased income distribution. However, consumption and investment decreased because of resource redirection to the war effort.

While military spending has had some positive effects over the years, the macroeconomic effects of military spending on major U.S. wars have been largely negative, according to an analysis by the Institute of Economics and Peace. War financing through debt, taxation, or inflation puts pressure on taxpayers, reduces private-sector consumption, and decreases investment.

U.S. Military Spending Relative to GDP

It’s important to note that while current U.S. military spending is higher than at any point of the Cold War (when adjusted for inflation), it is still low when considering defense spending as a percentage of the country’s GDP. The DOD has requested $850 billion in spending for 2025, which is about 3% of the GDP—that’s relatively low compared to other times in U.S. history. Looking at military spending in terms of GDP reveals that the U.S. economy has generally grown faster than military spending, so its share of the GDP has been lower. Military spending in the U.S. increased by 62% between 1980 and 2023, from $506 billion to $820 billion after adjusting for inflation. However, military spending still trails behind overall federal spending, which increased 175% over the same period.

What Country Spends the Most on the Military?

The United States spends the most on the military. In 2023, the U.S. accounted for about 40% of military spending worldwide, according to a report by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

What Percentage of Tax Dollars Go to Military Spending?

In 2023, the U.S. federal government spent $6.1 trillion. Of that, 13% of the budget, or $820 billion, was spent on military spending, including operations and maintenance, military personnel, weapons procurement, research, testing, and development.

What Was the Most Expensive War for the U.S.?

World War II was the most expensive war for the U.S. so far, costing nearly $6 trillion total in 2024 dollars. In the peak spending year, WWII expenditures accounted for 35.8% of the U.S. GDP.

The Bottom Line

The U.S. spends more on its military than any other country. The government has financed major wars by increasing taxes and debt and adjusting the money supply. Although military spending has reduced unemployment and has led to new developments in technology, the financing methods have increased inflationary pressures, causing negative long-term effects such as decreased purchasing power.

The larger macroeconomic consequences of large-scale military spending have included issues such as higher taxes, inflation, and larger government budget deficits.