From the studios of New York City, late-night television has long presented itself as more than entertainment. It has been a place where satire meets accountability. After January 3rd, the day US forces bombed Caracas and captured Nicolás Maduro, for the first time that familiar spotlight turned suddenly towards Venezuela.

Much of the humor that followed focused, understandably, on the actions of the United States. For American comedians, criticizing their own government, and how it deploys public money and military power, is not only natural, it is necessary. But these days, that aspiration of accountability has become hard to watch for Venezuelans who have been turned into a backdrop for these jokes.

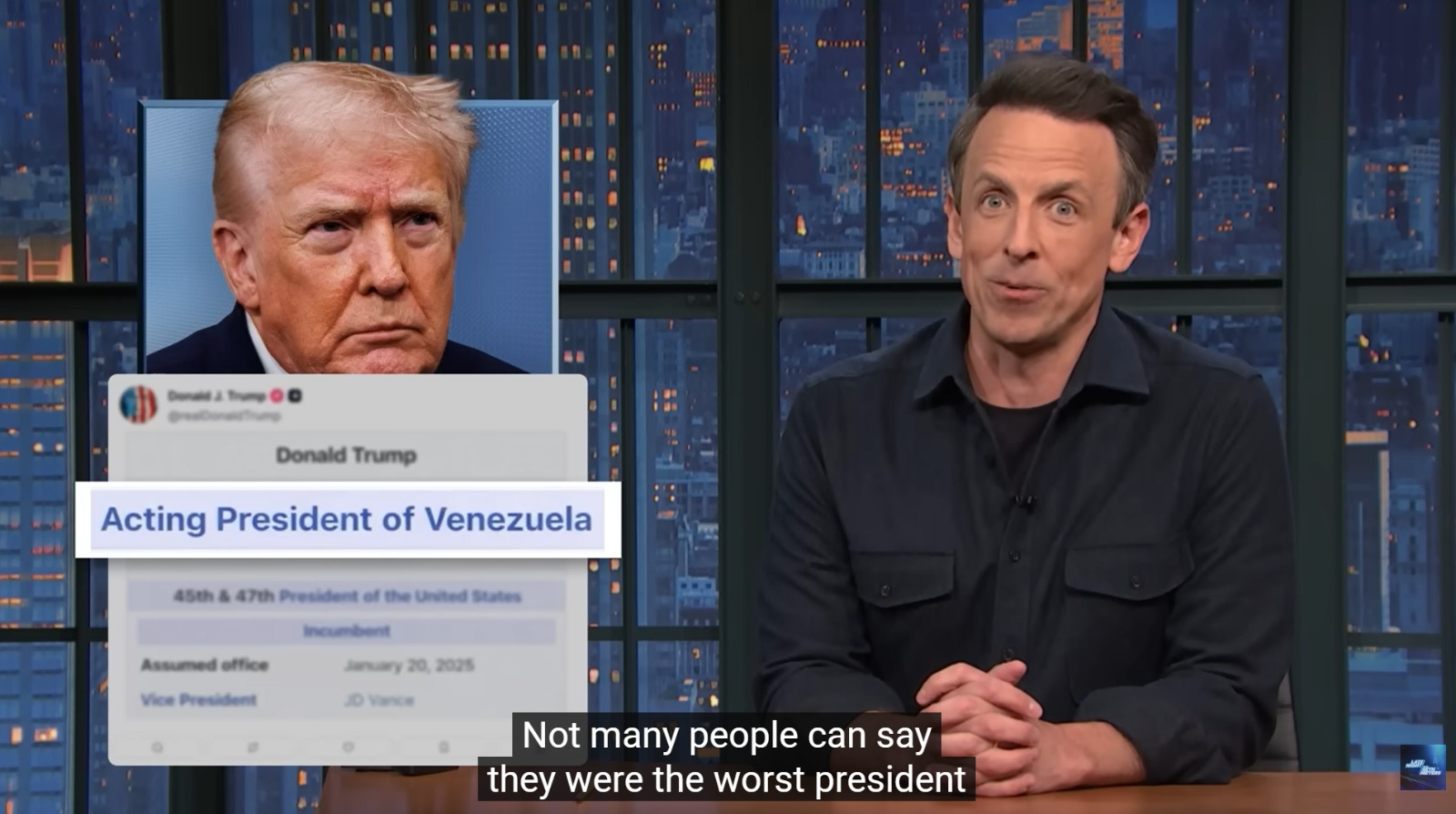

On Late Night, Seth Meyers joked about Donald Trump sharing a post that listed him as president of Venezuela, adding that “not many people can say they were the worst president in the history of two countries.” While a joke like that might land with the US audience, for Venezuelans it collapses two profoundly unequal realities into a punchline: equating the failures of a democratic system with life under an authoritarian regime marked by torture, political imprisonment, and forced exile. Similar tones appeared elsewhere, including when Jimmy Kimmel casually placed Trump and Maduro in the same category of “dictators”. Of course, the joke was never meant for Venezuelans. It was written for Americans. But in a media ecosystem where clips travel instantly across borders, the message is dangerous to Americans, Venezuelans and the whole internet.

Watching the reactions that followed the capture of Maduro has been difficult. For many people, especially those who grew up in countries with free media, functioning institutions, real alternation of power, and where dissent does not lead to imprisonment or torture, these guarantees feel not only universal, but almost invisible. They are so deeply embedded that they are taken for granted.

Over time, this invisibility becomes a form of privilege. The privilege of expressing political opinions without fear. The privilege of knowing your loved ones will return home for dinner. The privilege of discussing marxist theory and the perils of capitalism over expensive wine without having lived under regimes like those in Cuba, North Korea, Iran or, in this case, Venezuela. The privilege of not being able to imagine what life under such conditions looks like, because it feels, and is, so remote.

Three decades after Rwanda, amplified by social media, we now have a global civil society passionately defending international law. This advocacy matters.

This privilege shapes how international law is defended: as an abstract principle, rather than a fragile protection that often fails those who need it most.

Nice principles, bad timing

In recent days, international law has returned forcefully to the center of public debate. We are told it was violated. Foreign Affairs magazine warns of “a world without rules.” Social media debates argue that Venezuelans should have solved their problems internally, or that the United States should have respected international law. The European Union and UN bodies have issued statements expressing that they are “deeply shocked” and “strongly condemn” recent events. Political leaders have raised alarms about the dangers posed to the international system. Outrage has been swift and loud.

But what we, Venezuelans, find jarring is not the concern itself, but its timing.

For years, Venezuelans exhausted every institutional mechanism available to seek change: elections, negotiations, protests. Along the way, we documented abuses, appealed to international bodies, fled the country, and buried our dead. In response, the multilateral system produced reports, procedural delays, symbolic gestures—and, more often than not, only silence. Sanctions imposed by some states were loudly criticized and falsely blamed for empty shelves and shortages that were the result of years of mismanagement, corruption, and repression.

Meanwhile, Maduro’s regime systematically withdrew from scrutiny, obstructing or disengaging from international and regional mechanisms where it might have faced even limited accountability.

Today’s alarm stands in stark contrast to yesterday’s indifference.

Venezuela’s case, however, is not the first. In 1994, despite clear warnings, between 500,000 and 800,000 people were murdered in Rwanda while the international community debated mandates and political costs. “Never again” became a defining phrase of international law to ask for forgiveness after the genocide. And it has been forgiveness that has marked international law’s recent history. From Bosnia to Darfur, from Syria to Myanmar, atrocities have unfolded while international law remained intact on paper.

Recent history has shown that the UN remains profoundly ill-equipped to address situations in which the state itself becomes the main perpetrator of violence against its own population.

Three decades after Rwanda, amplified by social media, we now have a global civil society passionately defending international law. This advocacy matters. But recognizing it as a privilege is fundamental. In the case of Venezuela, much of this defense comes from the comfort of countries where having political opinions carries no personal risk, where dissent does not lead to prison, torture, or death. In this case it becomes easier to defend legal principles than to confront the human cost of their repeated failure.

The problem, then, is not that international law matters too much, but that it does selectively. When the United Nations was created, along with its Charter and the foundations of modern international law, its central purpose was to prevent the repetition of the horrors of World War II. This meant privileging diplomacy and peaceful dispute resolution over the use of force between states. Without a question through that lens, US military action in Caracas contradicts the very foundations of the system, and that is a very legitimate concern.

But what critics fail to acknowledge is that the UN was designed primarily to manage conflicts between states. Not as a way to govern those relationships, but a way to channel and address challenges in a world in a state of anarchy. Recent history has shown that it remains profoundly ill-equipped to address situations in which the state itself becomes the main perpetrator of violence against its own population. In such cases, sovereignty ceases to be a shield for people and becomes a shield for power.

Because it has become too often a system that protects sovereignty over people, stability over justice. As such, it has become an instrument that authoritarian regimes learn to weaponize, while its costs are borne by the most vulnerable.

The space opened by bombs

In Venezuela, people do not live in fear of foreign bombs from the US. They live in fear of empty shelves, intelligence services, arbitrary detention, torture, and death. Any discussion that elevates abstract legal violations while sidelining this reality risks becoming not principled, but condescending.

The same is true of narratives that reduce everything to cynical explanations about US interests, as if Venezuelans were naïve about power or unaware of geopolitics. We are not confusing interests with ideals. What many of us recognize is that a long-frozen status quo, one that normalized repression and indefinite stagnation, has been disrupted. That disruption does not guarantee democracy. But it opens a space that did not exist before, and gives us hope.

The key challenge moving forward is not whether Venezuelans should patiently wait for the international community to act according to international law while continuing to document abuses. It is whether defenders of the system are willing to acknowledge its limits and to stop confusing inaction with virtue.

International law is worth defending. But defending it without reckoning with its persistent failures in countries like Venezuela simply showcases a position of privilege—one that Venezuelans, or Iranians, can no longer afford.

Elie Wiesel warned in his address to the US Congress that indifference is never neutral. It always benefits the oppressor, never the victim. Those who defend international law still have an opportunity to prove that they truly care about the people it was meant to protect. A couple of big actions that go further than strongly condemning or being shocked is to push for the immediate and unconditional release of all political prisoners, enforce asset freezes against the regime and its enablers, and stop treating accountability as optional. And they could do so consistently—in Venezuela, in Iran, and wherever international law is invoked loudly, but applied timidly.