WASHINGTON — Top officials in the Trump administration clarified their position on “running” Venezuela after seizing its president, Nicolás Maduro, over the weekend, pressuring the regime that remains in power there Sunday to acquiesce to U.S. demands on oil access and drug enforcement, or else face further military action.

Their goal appears to be the establishment of a pliant vassal state in Caracas that keeps the current government — led by Maduro for more than a decade — largely in place, but finally defers to the whims of Washington after turning away from the United States for a quarter century.

It leaves little room for the ascendance of Venezuela’s democratic opposition, which won the country’s last national election, according to the State Department, European capitals and international monitoring bodies.

Trump and his top aides said they would try to work with Maduro’s handpicked vice president and current interim president, Delcy Rodríguez, to run the country and its oil sector “until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” offering no time frame for proposed elections.

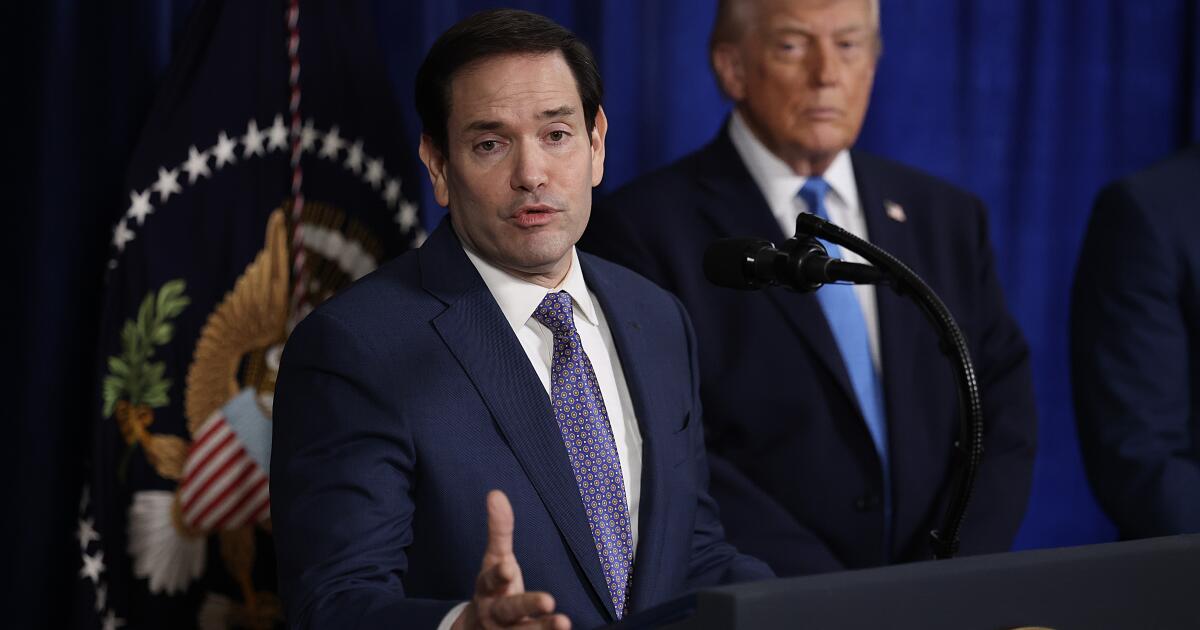

Trump, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem underscored the strategy in a series of interviews Sunday morning.

“If she doesn’t do what’s right, she is going to pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro,” Trump told the Atlantic, referring to Rodríguez. “Rebuilding there and regime change, anything you want to call it, is better than what you have right now. Can’t get any worse.”

Rubio said that a U.S. naval quarantine of Venezuelan oil tankers would continue unless and until Rodríguez begins cooperating with the U.S. administration, referring to the blockade — and the lingering threat of additional military action from the fleet off Venezuela’s coast — as “leverage” over the remnants of Maduro’s regime.

“That’s the sort of control the president is pointing to when he says that,” Rubio told CBS News. “We continue with that quarantine, and we expect to see that there will be changes — not just in the way the oil industry is run for the benefit of the people, but also so that they stop the drug trafficking.”

Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.), chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, told CNN that he had been in touch with the administration since the Saturday night operation that snatched Maduro and his wife from their bedroom, whisking them away to New York to face criminal charges.

Trump’s vow to “run” the country, Cotton said, “means the new leaders of Venezuela need to meet our demands.”

“Delcy Rodríguez, and the other ministers in Venezuela, understand now what the U.S. military is capable of,” Cotton said, while adding: “It is a fact that she and other indicted and sanctioned individuals are in Venezuela. They have control of the military and security forces. We have to deal with that fact. But that does not make them the legitimate leaders.”

“What we want is a future Venezuelan government that will be pro-American, that will contribute to stability, order and prosperity, not only in Venezuela but in our own backyard. That probably needs to include new elections,” Cotton added.

Whether Rodríguez will cooperate with the administration is an open question.

Trump said Saturday that she seemed amenable to making “Venezuela great again” in a conversation with Rubio. But the interim president delivered a speech hours later demanding Maduro’s return, and vowing that Venezuela would “never again be a colony of any empire.”

The developments have concerned senior figures in Venezuela’s democratic opposition, led by Maria Corina Machado, last year’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and Edmundo González Urrutia, the opposition candidate who won the 2024 presidential election that was ultimately stolen by Maduro.

In his Saturday news conference, Trump dismissed Machado, saying that the revered opposition leader was “a very nice woman,” but “doesn’t have the respect within the country” to lead.

Elliott Abrams, Trump’s special envoy to Venezuela in his first term, said he was skeptical that Rodríguez — an acolyte of Hugo Chávez and avowed supporter of Chavismo throughout the Maduro era — would betray the cause.

“The insult to Machado was bizarre, unfair — and simply ignorant,” Abrams told The Times. “Who told him that there was no respect for her?”

Maduro was booked in New York and flown by night over the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor to the Metropolitan Detention Center in Brooklyn, where he is in federal custody at a notorious facility that has housed other famous inmates, including Sean “Diddy” Combs, Ghislaine Maxwell, Bernie Madoff and Sam Bankman-Fried.

He is expected to be arraigned on federal charges of narco-terrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, possession of machine guns and destructive devices, and conspiracy to possess machine guns and destructive devices as soon as Monday.

While few in Washington lamented Maduro’s ouster, Democratic lawmakers criticized the operation as another act of regime change by a Republican president that could have violated international law.

“The invasion of Venezuela has nothing to do with American security. Venezuela is not a security threat to the U.S.,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, a Democrat from Connecticut. “This is about making Trump’s oil industry and Wall Street friends rich. Trump’s foreign policy — the Middle East, Russia, Venezuela — is fundamentally corrupt.”

In their Saturday news conference, and in subsequent interviews, Trump and Rubio said that targeting Venezuela was in part about reestablishing U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere, reasserting the philosophy of President James Monroe as China and Russia work to enhance their presence in the region. The Trump administration’s national security strategy, published last month, previewed a renewed focus on Latin America after the region faced neglect from Washington over decades.

Trump left unclear whether his military actions in the region would end in Caracas, a longstanding U.S. adversary, or if he is willing to turn the U.S. armed forces on America’s allies.

In his interview with the Atlantic, Trump suggested that “individual countries” would be addressed on a case-by-case basis. On Saturday, he reiterated a threat to the president of Colombia, a major non-NATO ally, to “watch his ass,” over an ongoing dispute about Bogota’s cooperation on drug enforcement.

On Sunday morning, the United Nations Security Council was called for an urgent meeting to discuss the legality of the U.S. operation inside Venezuela.

It was not Russia or China — permanent members of the council and longstanding competitors — who called the session, nor France, whose government has questioned whether the operation violated international law, but Colombia, a non-permanent member who joined the council less than a week ago.