Can India switch from Russian to Venezuelan oil, as Trump wants? | Energy News

New Delhi, India – When US President Donald Trump announced a trade deal with India on Monday this week, he declared that New Delhi would pivot away from Russian energy as part of the agreement.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Trump said, had promised to stop buying Russian oil, and instead buy crude from the United States and from Venezuela, whose president, Nicolas Maduro, was abducted by US special forces in early January. Since then, the US has effectively taken control of Venezuela’s mammoth oil industry.

In return, Trump dialled down trade tariffs on Indian goods from an overall 50 percent to just 18 percent. Half of that 50 percent tariff was levied last year as punishment for India buying Russian oil, which the White House maintains is financing Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine.

But since Monday, India has not publicly confirmed that it has committed to either ceasing its purchase of Russian oil or embracing Venezuelan crude, analysts note. Dmitry Peskov, a Kremlin spokesperson, told reporters on Tuesday that Russia had received no indication of this from India, either.

And switching from Russian to Venezuelan oil will be far from straightforward. A cocktail of other factors – shocks to the energy market, costs, geography, and the characteristics of different kinds of oil – will complicate New Delhi’s decisions about its sourcing of oil, they say.

So, can India really dump Russian oil? And can Venezuelan crude replace it?

What is Trump’s plan?

Trump has been pressuring India to stop buying Russian oil for months. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the US and European Union placed an oil price cap on Russian crude in a bid to limit Russia’s ability to finance the war.

As a result, other countries including India began buying large quantities of cheap Russian oil. India, which before the war sourced only 2.5 percent of its oil from Russia, became the second-largest consumer of Russian oil after China. It currently sources around 30 percent of its oil from Russia.

Last year, Trump doubled trade tariffs on Indian goods from 25 percent to 50 percent as punishment for this. Later in the year, Trump also imposed sanctions on Russia’s two biggest oil companies – and threatened secondary sanctions against countries and entities that trade with these firms.

Since the abduction of Maduro by US forces in early January, Trump has effectively taken over the Venezuelan oil sector, controlling sales cash flows.

Venezuela also has the largest proven oil reserves in the world, estimated at 303 billion barrels, more than five times larger than those of the US, the world’s largest oil producer.

But while getting India to buy Venezuelan oil makes sense from the US’s perspective, analysts say this could be operationally messy.

How much oil does India import from Russia?

India currently imports nearly 1.1 million barrels per day (bpd) of Russian crude, according to analytics company Kpler. Under Trump’s mounting pressure, that is lower than the average 1.21 million bpd in December 2025 and more than 2 million bpd in mid-2025.

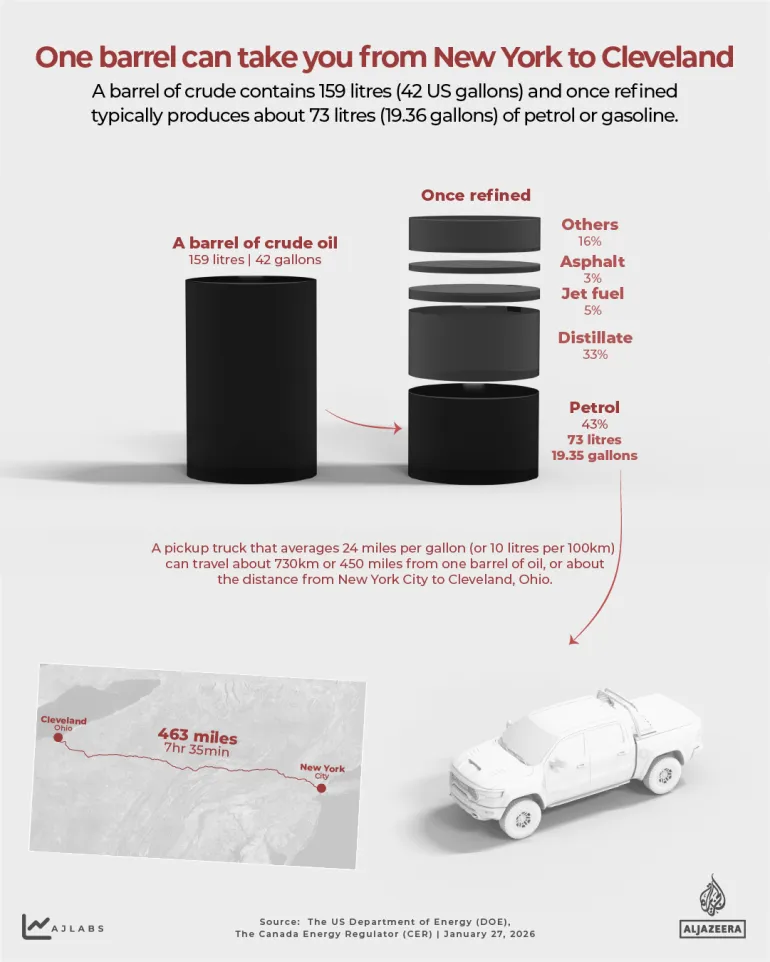

One barrel is equivalent to 159 litres (42 gallons) of crude oil. Once refined, a barrel typically produces about 73 litres (19 gallons) of petrol for a car. Oil is also refined to produce a wide variety of products, from jet fuel to household items including plastics and even lotions.

Has India stopped Russian oil purchases?

India has reduced the amount of oil it buys from Russia over the past year, but it has not stopped buying it altogether.

Under increasing pressure from Trump, last August, Indian officials called out the “hypocrisy” of the US and EU pressuring New Delhi to back off from Russian crude.

“In fact, India began importing from Russia because traditional supplies were diverted to Europe after the outbreak of the conflict,” Randhir Jaiswal, India’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson, said then. He added that India’s decision to import Russian oil was “meant to ensure predictable and affordable energy costs to the Indian consumer”.

Despite this, Indian refiners, currently the second-largest group of buyers of Russian oil after China, are reportedly winding up their purchases after clearing current scheduled orders.

Major refiners like Hindustan Petroleum Corporation Ltd (HPCL), Mangalore Refinery and Petrochemicals Ltd (MRPL), and HPCL-Mittal Energy Ltd (HMEL) halted purchasing from Russia following the US sanctions against Russian oil producers last year.

Other players like Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), Bharat Petroleum Corporation, and Reliance Industries will soon stop their purchases.

What happens if India suddenly stops buying Russian oil?

Even if India wanted to stop importing Russian oil altogether, analysts argue it would be extremely costly to do so.

In September last year, India’s oil and petroleum minister, Hardeep Singh Puri, told reporters that it would also sharply push up energy prices and fuel inflation. “The world will face serious consequences if the supplies are disrupted. The world can’t afford to keep Russia off the oil market,” Puri said.

Analysts tend to agree. “A complete cessation of Indian purchases of Russian oil would be a major disruption. An immediate halt would spike global prices and threaten India’s economic growth,” said George Voloshin, an independent energy analyst based in Paris.

Russian oil would likely be diverted more heavily towards China and into “shadow” fleets of tankers that deliver sanctioned oil secretly by flying false flags and switching off location equipment, Voloshin told Al Jazeera. “Mainstream tanker demand would shift toward the Atlantic Basin, most likely increasing global freight rates as a result,” he noted.

Sumit Pokharna, vice president at Kotak Securities, noted that Indian refineries have reported robust margins in the last two years, majorly benefitting from the discounted Russian crude.

“If they move to higher-costing, like the US or Venezuela, then raw material cost would increase, and that would squeeze their margins,” he told Al Jazeera. “If it goes beyond control, they may have to pass the excess onto consumers.”

Can India stop buying Russian oil altogether?

It may not be able to. One of India’s two private refiners, Nayara Energy, is majority-Russian-owned and under heavy Western sanctions. The Russian energy firm Rosneft holds a 49.13 percent stake in the company, which operates a 400,000-barrel-per-day refinery in India’s Gujarat, PM Modi’s home state.

Nayara is the second-largest importer of Russian crude, buying about 471,000 barrels per day in January this year, accounting for nearly 40 percent of Russian supplies to India.

Its plant has relied solely on Russian crude since European Union sanctions were imposed on the company last July.

Nayara is not planning to load Russian oil in April as it shuts its refinery for more than a month for maintenance from April 10, according to Reuters.

Pokharna said the future of Nayara hangs in the balance, with the US unlikely to grant India an overt exemption for the Russia-backed company to import crude.

Can India switch to Venezuelan oil?

India has been a major consumer of Venezuelan oil in the past. At its peak, in 2019, India imported $7.2bn of oil, accounting for just under 7 percent of total imports. That stopped after the US slapped sanctions on Venezuelan oil, but some officials of the government-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation are still stationed in the Latin American country.

Now, major Indian refiners have said they are open to receiving Venezuelan oil again, but only if it is a viable option.

For one thing, Venezuela is roughly twice as far from India as Russia and five times further than the Middle East, meaning much higher freight costs.

Venezuelan oil is more expensive as well. “Russian Urals [a medium-heavy crude blend] has been trading at a wide-ranging discount of about $10-20 per barrel to Brent, while Venezuelan Merey currently offers a smaller discount of around $5-8 per barrel,” Voloshin told Al Jazeera.

“Importing from Venezuela and forgoing the Russian discount would be a costly affair for India,” said Pokharna. “From transportation cost to forgoing discounts, it could cost India $6-8 more per barrel – and that is a huge increase in the importing bill.”

Overall, a complete pivot away from Russia could raise India’s import bill by $9bn to $11bn – an amount roughly equal to India’s federal health budget – per year, according to Kpler.

“Venezuelan crude must be discounted by at least $10 to $12 per barrel to be competitive,” argued Voloshin. “This deeper discount is necessary to offset the much higher freight costs, increased insurance premiums for the longer Atlantic voyage, and the somewhat higher operational expenses required to process Venezuela’s extra-heavy high-sulfur crude.”

Without deeper discounts, the longer journey and complex handling make Venezuelan oil more expensive on a delivered basis, he added.

Another major issue is that many Indian refiners simply do not have the facilities to process very heavy Venezuelan oil.

Venezuelan crude is a heavy, sour oil, thick and viscous like molasses, with a high sulphur content requiring complex, specialised refineries to process it into fuel. Only a small number of Indian refineries are equipped to handle it.

“[Venezuelan oil’s heaviness] makes it an option only for complex refineries, leaving out older and smaller refineries,” Pokharna told Al Jazeera. “The shift is operationally difficult and would require blending with more expensive light crudes.”

Then there is the question of availability. Today, Venezuela produces barely a million barrels per day when pushed to its limit. Even if all production was sent to India, it would not match the total Russian oil import.

Where else could India buy oil?

India’s Minister Puri has said that New Delhi is looking to diversify sourcing options from nearly 40 countries.

As India has reduced Russian imports, it has increased them from Middle Eastern nations and other countries in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Now, while Russia accounts for nearly 27 percent share in India’s oil imports, OPEC nations, led by Iraq and Saudi Arabia, contribute 53 percent.

Reeling from Trump’s trade war, India has also increased purchases of US oil. American crude imports to India rose by 92 percent from April to November in 2025 to nearly 13 million tons, compared to 7.1 million in the same period in 2024.

However, India would be competing for these supplies with the European Union, which has pledged to spend $750bn by 2028 on US energy and nuclear products.

Meanwhile, for Venezuela to return to higher production, Caracas needs political stability, changes in foreign investment and oil laws, and to clear debts. That will take time, experts say.