Sudan condemns RSF chief’s visit to Uganda as minimising ‘human values’ | Sudan war News

Uganda Ministry of Foreign Affairs says Mohamed Dagalo’s meeting with President Yoweri Museveni focused on ending war.

Sudan has condemned Uganda for hosting the head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, as an “insult” to humanity and the Sudanese people.

In a statement on Sunday, Sudan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs denounced the reception of Dagalo, also known as “Hemedti”, in the “strongest terms” and his meeting on Friday with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

“This unprecedented step insults humanity before it insults the Sudanese people, and at the same time, it disregards the lives of innocent people killed due to the behaviour of Hemedti and his terrorist militia,” the Foreign Ministry wrote.

Rights groups and international organisations have accused the RSF of war crimes and targeting civilians in Sudan.

Khartoum said hosting Dagalo “disregards” human values.

It “completely disregards the laws governing relations between member states of regional and international organisations that prohibit providing any support for rebel forces against a legitimate, internationally recognised government”, the Foreign Ministry added.

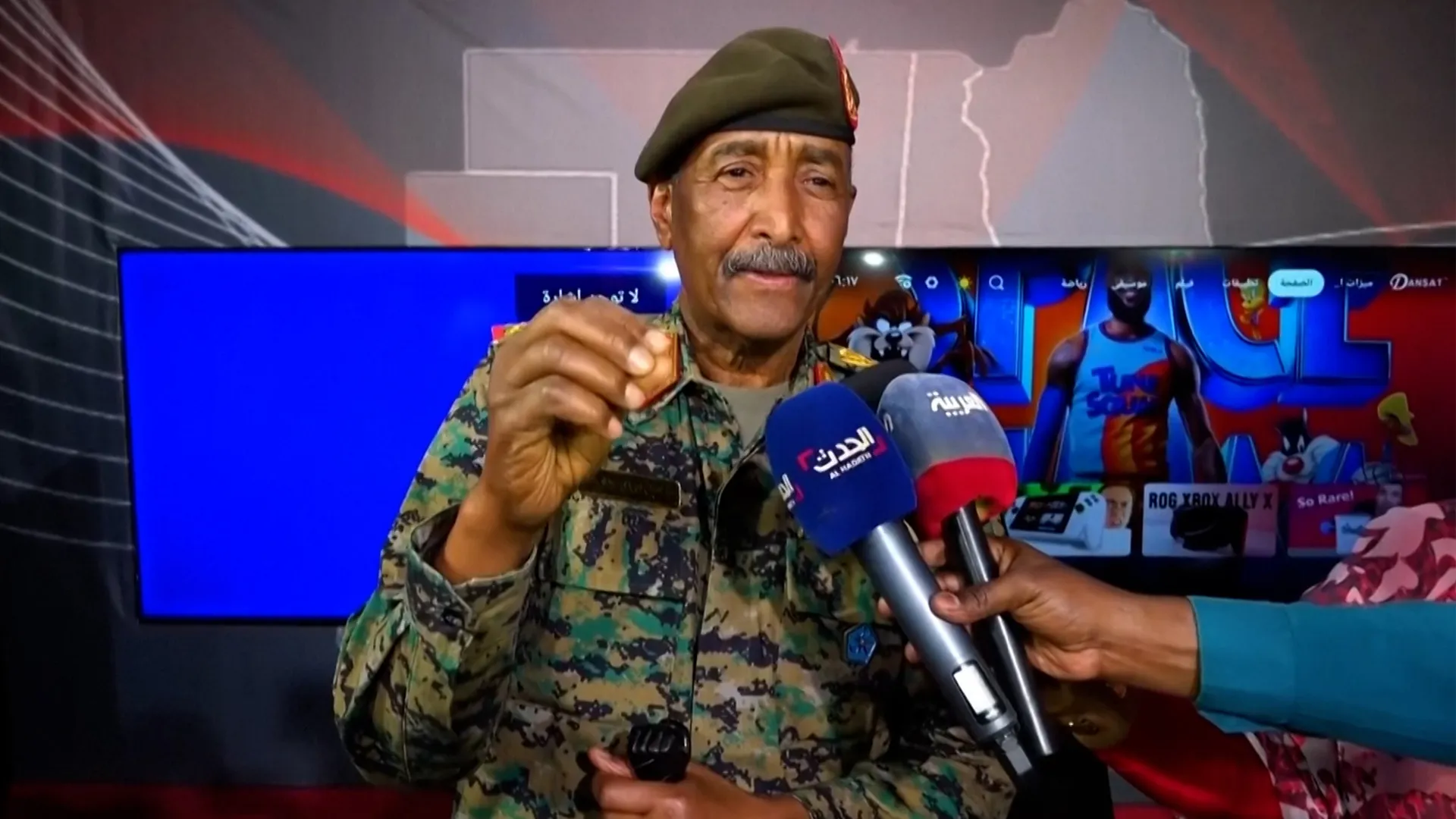

In 2023, Sudan was plunged into a civil war between the Sudanese army, led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and the RSF.

According to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), at least 11.7 million people have been displaced by the conflict and an estimated 150,000 people have been killed.

Last week, the United States imposed sanctions on three RSF commanders over their alleged roles in the 18-month siege and capture of el‑Fasher, the capital of North Darfur State in western Sudan.

In a statement, the US Department of the Treasury accused the RSF of perpetrating “a horrific campaign of ethnic killings, torture, starvation, and sexual violence” during the siege and capture of el-Fasher, which fell to the RSF in October.

Separately, a UN mission found that the RSF campaign in el-Fasher was a “planned and organised operation that bears the defining characteristics of genocide”.

‘Poisonous’ identity politics

Uganda’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued its own statement on Dagalo’s visit and said his meeting with Museveni focused on “ending the ongoing conflict in Sudan and restoring regional stability”.

Museveni reiterated in his remarks to Hemedti that peace in Sudan could only be achieved through dialogue and warned against what he described as identity politics.

“When I last came to Sudan, I met [former] President [Omar al-] Bashir and advised against the politics of identity instead of the politics of interest,” Museveni said.

“Identity politics is poisonous. It does not yield good results. What is important are shared interests that unite people,” he said while calling for both parties to prioritise “peace over military confrontation”.

For his part, Dagalo thanked Museveni and said he shares the Ugandan president’s “principles and your commitment to peace”, according to a statement released by the Ugandan government.

“He noted that Sudan continues to face serious humanitarian and institutional challenges as a result of the conflict and stressed the need for a peaceful resolution,” the statement added.