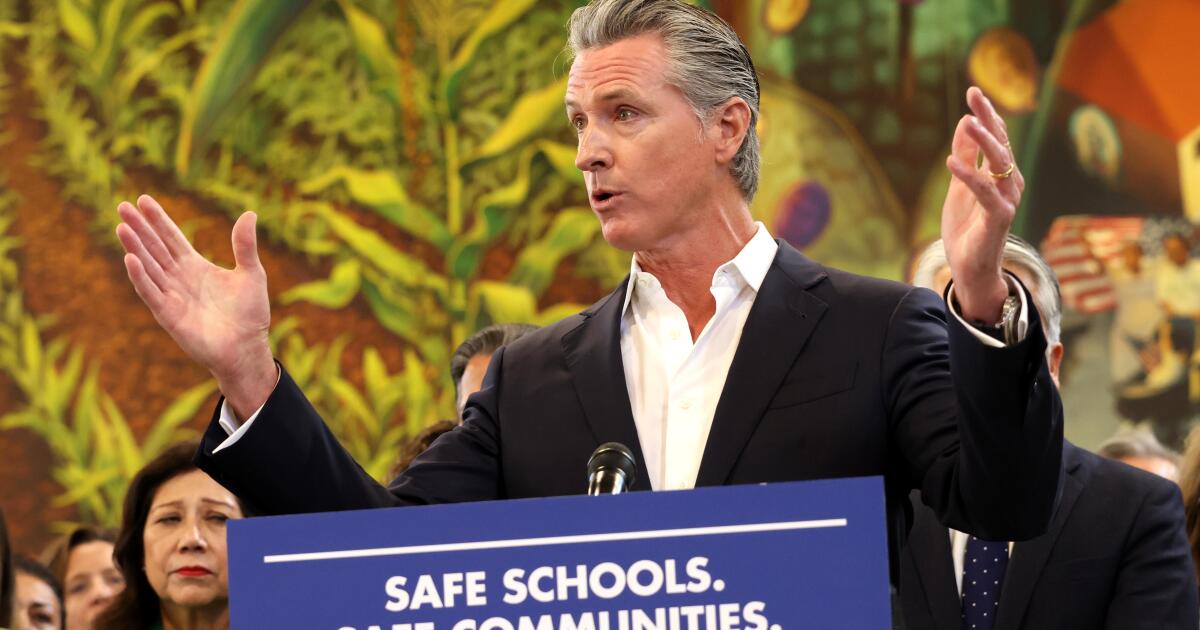

Newsom walks thin line on immigrant health as he eyes presidential bid

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has acknowledged he is eyeing a presidential bid, has incensed both Democrats and Republicans over immigrant healthcare, underscoring the delicate political path ahead.

For a second straight year, the Democrat has asked state lawmakers to roll back coverage for some immigrants in the face of federal Medicaid spending cuts and a roughly $3-billion budget deficit that analysts warn could worsen if the AI bubble bursts. Newsom has proposed that the state not step in when, starting in October, the federal government stops providing health coverage to an estimated 200,000 legal residents — comprising asylees, refugees and others.

Progressive legislators and activists said the cost-saving measures are a departure from Newsom’s “health for all” pledge, and Republicans continue to skewer Newsom for using public funds to cover any noncitizens.

Newsom’s latest move would save an estimated $786 million this fiscal year and $1.1 billion annually in future years in a proposed budget of $349 billion, according to the Department of Finance.

State Sen. Caroline Menjivar, one of two Senate Democrats who voted against Newsom’s immigrant health cuts last year, said she worried the governor’s political ambition could be getting in the way of doing what’s best for Californians.

“You’re clouded by what Arkansas is going to think, or Tennessee is going to think, when what California thinks is something completely different,” said Menjivar, who said previous criticism got her temporarily removed from a key budget subcommittee. “That’s my perspective on what’s happening here.”

Meanwhile, Republican state Sen. Tony Strickland criticized Newsom for glossing over the state’s structural deficit, which state officials say could balloon to $27 billion the following year. And he slammed Newsom for continuing to cover California residents in the U.S. without authorization. “He just wants to reinvent himself,” Strickland said.

It’s a political tightrope that will continue to grow thinner as federal support shrinks amid ever-rising healthcare expenses, said Guian McKee, a co-chair of the Health Care Policy Project at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center of Public Affairs.

“It’s not just threading one needle but threading three or four of them right in a row,” McKee said. Should Newsom run for president, McKee added, the priorities of Democratic primary voters — who largely mirror blue states like California — look very different from those in a far more divided general electorate.

Americans are deeply divided on whether the government should provide health coverage to immigrants without legal status. In a KFF poll last year, a slim majority — 54% — were against a provision that would have penalized states that use their own funds to pay for immigrant healthcare, with wide variation by party. The provision was left out of the final version of the bill passed by Congress and signed by President Trump.

Even in California, support for the idea has waned amid ongoing budget problems. In a May survey by the Public Policy Institute of California, 41% of adults in the state said they supported providing health coverage to immigrants without authorization, a sharp drop from the 55% who supported it in 2023.

Trump, Vice President JD Vance, other administration officials, and congressional Republicans have repeatedly accused California and other Democrat-led states of using taxpayer funds on immigrant healthcare, a red-meat issue for their GOP base. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Mehmet Oz has accused California of “gaming the system” to receive more federal funds, freeing up state coffers for its Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal, which has enrolled roughly 1.6 million immigrants without legal status.

“If you are a taxpayer in Texas or Florida, your tax dollars could’ve been used to fund the care of illegal immigrants in California,” he said in October.

California state officials have denied the charges, noting that only state funds are used to pay for general health services to those without legal status because the law prohibits using federal funds. Instead, Newsom has made it a “point of pride” that California has opened up coverage to immigrants, which his administration has noted keeps people healthier and helps them avoid costly emergency room care often covered at taxpayer expense.

“No administration has done more to expand full coverage under Medicaid than this administration for our diverse communities, documented and undocumented,” Newsom told reporters in January. “People have built careers out of criticizing my advocacy.”

Newsom warns the federal government’s “carnival of chaos” passed Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which he said puts 1.8 million Californians at risk of losing their health coverage with the implementation of work requirements, other eligibility rules, and limits to federal funding to states.

Nationally, 10 million people could lose coverage by 2034, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Health economists have said higher numbers of uninsured patients — particularly those who are relatively healthy — could concentrate coverage among sicker patients, potentially increasing premium costs and hospital prices overall.

Immigrant advocates say it’s especially callous to leave residents who may have fled violence or survived trafficking or abuse without access to healthcare. Federal rules currently require state Medicaid programs to cover “qualified noncitizens” including asylees and refugees, according to Tanya Broder with the National Immigration Law Center. But the Republican tax-and-spending law ends the coverage, affecting an estimated 1.4 million legal immigrants nationwide.

With many state governors yet to release budget proposals, it’s unclear how they might handle the funding gaps, Broder said.

For instance, Colorado state officials estimate roughly 7,000 legal immigrants could lose coverage due to the law’s changes. And Washington state officials estimate 3,000 refugees, asylees, and other lawfully present immigrants will lose Medicaid.

Both states, like California, expanded full coverage to all income-eligible residents regardless of immigration status. Their elected officials are now in the awkward position of explaining why some legal immigrants may lose their healthcare coverage while those without legal status could keep theirs.

Last year, spiraling healthcare costs and state budget constraints prompted the Democratic governors of Illinois and Minnesota, potential presidential contenders JB Pritzker and Tim Walz, to pause or end coverage of immigrants without legal status.

California lawmakers last year voted to eliminate dental coverage and freeze new enrollment for immigrants without legal status and, starting next year, will charge monthly premiums to those who remain. Even so, the state is slated to spend $13.8 billion from its general fund on immigrants not covered by the federal government, according to Department of Finance spokesperson H.D. Palmer.

At a news conference in San Francisco in January, Newsom defended those moves, saying they were necessary for “fiscal prudence.” He sidestepped questions about coverage for asylees and refugees and downplayed the significance of his proposal, saying he could revise it when he gets a chance to update his budget in May.

Kiran Savage-Sangwan, executive director of the California Pan-Ethnic Health Network, pointed out that California passed a law in the 1990s requiring the state to cover Medi-Cal for legal immigrants when federal Medicaid dollars won’t. This includes green-card holders who haven’t yet met the five-year waiting period for enrolling in Medicaid.

Calling the governor’s proposal “arbitrary and cruel,” Savage-Sangwan criticized his choice to prioritize rainy-day fund deposits over maintaining coverage and said blaming the federal government was misleading.

It’s also a major departure from what she had hoped California could achieve on Newsom’s first day in office seven years ago, when he declared his support for single-payer healthcare and proposed extending health insurance subsidies to middle-class Californians.

“I absolutely did have hope, and we celebrated advances that the governor led,” Savage-Sangwan said. “Which makes me all the more disappointed.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling and journalism.