ATLANTA — It is a goal spreading among anti-tax crusaders — eliminate all property taxes on homeowners.

Rising property values have inflated tax bills in many states, but ending all homeowner taxes would cost billions or even tens of billions in most states. It is unclear whether lawmakers can pull it off without harming schools and local governments that rely on the taxes to provide services.

Officials in North Dakota say they are on their way, using state oil money. Wednesday, Republicans in the Georgia House unveiled a complex effort to phase out homeowner property taxes by 2032. In Florida, GOP Gov. Ron DeSantis says that is his goal, with lawmakers considering phasing out nonschool property taxes on homeowners over 10 years. And in Texas, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott says he wants to eliminate property taxes for schools.

Republicans are echoing those who say taxes, especially when the tax collector can seize a house for nonpayment, mean no one truly owns property.

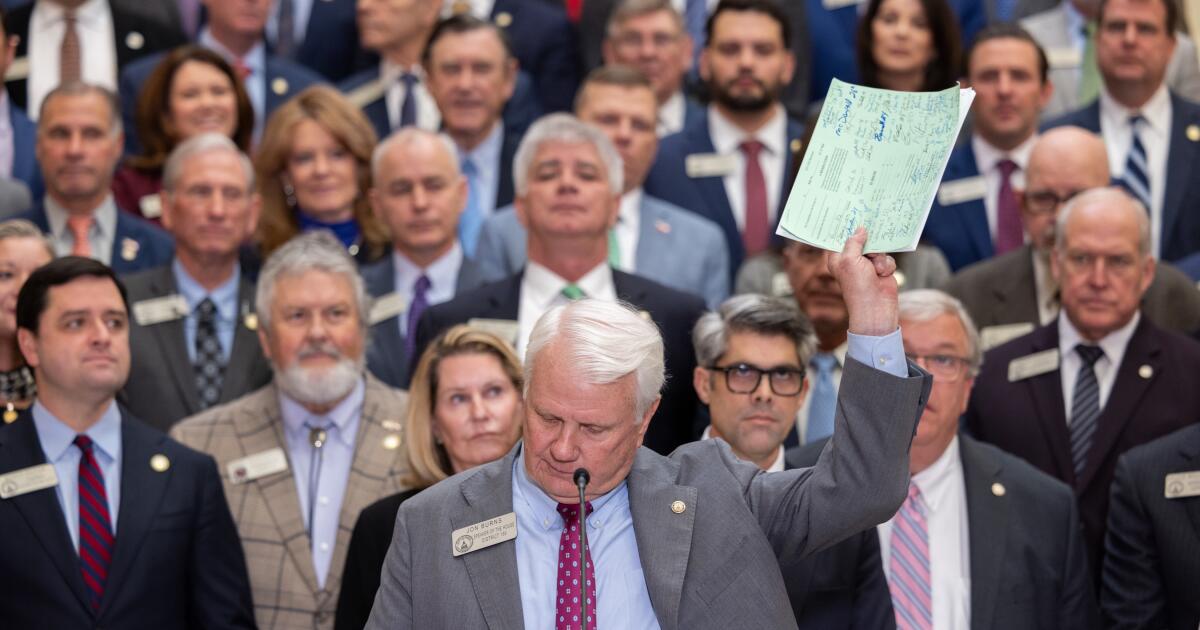

“No one should ever face the loss of their home because they can’t pay rent to the government,” Georgia Republican House Speaker Jon Burns of Newington said Wednesday.

An election-year tax revolt

These audacious election-year efforts could be joined by ballot initiatives in Oklahoma and Ohio to eliminate all property taxes. Such initiatives were defeated in North Dakota in 2024 and failed to make the ballot in Nebraska that year, although organizers there are trying again. Another initiative in Michigan may also fail to make the ballot.

“We’re very much in this property tax revolt era, which is not unique, it’s not new. We’ve seen these revolts in the past,” said Manish Bhatt, vice president of state tax policy at the Tax Foundation, a Washington, D.C., group that is generally skeptical of new taxes.

Previous backlashes led to laws like California’s Proposition 13, a 1978 initiative that limited property tax rates and how much local governments could increase property valuations for tax purposes.

The efforts are aimed at voters like Tim Hodnett, a 65-year-old retiree in suburban Atlanta’s Lawrenceville. Hodnett’s annual property tax bill rose from $2,000 to $3,000 between 2018 and 2024. He sees those figures starkly because he paid off his mortgage years ago, and he pays his taxes all at once instead of making monthly payments.

Hodnett said he is disabled and living on $30,000 a year. He is about to get a big property tax break, because seniors in Gwinnett County are exempt from school property taxes, about two-thirds of his bill. But he would love not to pay that other $1,000.

“It would be nice to be exempt from property taxes,” Hodnett said.

Will there be replacement revenue?

The question is whether local governments and K-12 schools should be expected to cut spending, or whether they will be allowed to make up revenue from some other source.

“I think the complete elimination of the property tax for homeowners is really going to be very difficult in most states and localities around the country, and undesirable in most places,” said Adam Langley of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a Massachusetts nonprofit that studies land use and taxation.

Florida Chief Financial Officer Blaise Ingoglia, a Republican, has been touring the state arguing that local governments are overspending, trying to show they don’t need the $19 billion in property taxes they collect from homeowners for whom the property is their primary residence. Local governments have been disputing those figures.

North Dakota is using earnings from the state’s $13.4-billion oil tax savings account to gradually wipe out homeowner property taxes. Last year, North Dakota’s Republican-controlled Legislature expanded its primary residence tax credit from $500 to $1,600 a year. Officials in December said the tax credit wiped out property taxes for 50,000 households last year and reduced bills for nearly 100,000 more. That cost $400 million in state subsidies for the 2025 and 2026 tax years.

“It works, and we know we can build on it to provide even more relief and get property taxes to zero for the vast majority of North Dakota homeowners,” Republican Gov. Kelly Armstrong said.

The situation is murkier in Texas, which has been using state surplus funds to finance property tax reductions, and under the Georgia proposal, which calls for shifting taxes around.

A shift from property to sales taxes

Burns wants Georgia to wipe out $5.2 billion in homeowner property taxes — more than a quarter of the $19.9 billion in property taxes collected in 2024 — telling cities, counties and school districts to fall back on current or new sales taxes.

Not only will Burns’ plan need the Republican-led Senate to agree, but it will require Democratic support to meet the two-thirds hurdle for a state constitutional amendment and then voter approval in November.

While most property taxes go to schools, the majority of sales taxes don’t in some communities. It is unclear whether localities would redivide sales taxes. Also, local governments and schools would remain limited to a combined 5% sales tax rate, atop the state’s 4% rate. Some schools and governments might not be able to raise sales taxes enough to recover lost revenue.

Georgia would go from currently shielding $5,000 in home value from taxation to $150,000 in 2031 before abolishing most homeowner property taxes in 2032. The plan would limit yearly property tax revenue growth to 3% on other kinds of property.

Local governments would able to send homeowners a yearly bill for specified services such as garbage pickup, street lighting, stormwater control and fire protection, but lawmakers aren’t calling that a tax. Voters could also approve assessments for government or school improvements. Authors said they haven’t decided whether property owners could lose homes for unpaid assessments.

Burns also wants to spend about $1 billion to cut property tax bills in 2026, but it is unclear whether Republican Gov. Brian Kemp will agree. A spokesperson declined to comment.

Georgia previously tried to limit how much home values could rise for tax purposes, one common approach nationwide. But a majority of school districts and many other local governments have opted out. Georgia’s senators are still pursuing that approach, with a Senate committee on Wednesday voting to make the limit mandatory.

Amy writes for the Associated Press. AP writer Jack Dura in Bismarck, N.D., contributed to this report.