Pivot to Arctic: Why the Mastery of the North Matters?

Introduction

The Arctic has long been known as “high North, low tension”, as its frozen waters and permafrost landscape offered no incentives to the states. However, due to global warming, it is changing. The rate of warming in the Arctic region is four times faster than the globe, resulting in massive ice loss. This anthropogenic anomaly has made the Arctic a region of geopolitical significance.

The Strategic Importance

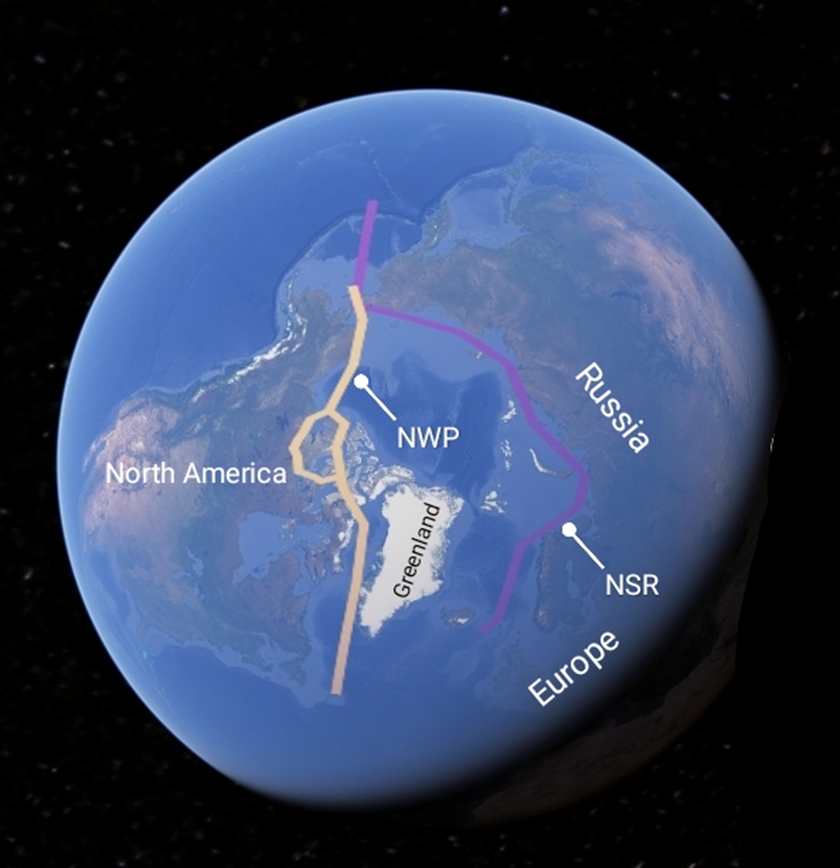

The strategic importance of any region primarily depends on two factors: The first is Geographical position; which not only emboldens its importance as a trade passage but also defines its fruitfulness as a strategic location in both peace and war. The second; its Resources which offer economic benefits to the states, which can be translated into military might. The Arctic, indeed, has manifested both qualities. Its seas are becoming navigable as the ice recedes. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) and the Northwest passage (NWP) provide the countries in the high latitudes lucrative trade opportunities. Similarly, the geo-economic weight of the Arctic is augmented by its huge reserves of petroleum and minerals. It holds almost 13% (90 billion barrels) of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30% of its undiscovered gas resources. Moreover, the Arctic has a large amount of mineral resources. For example, Greenland; which comprises almost 15% of the Arctic region and its second largest contiguous landmass, is estimated to possess large deposits of Rare Earths, Copper, Zinc, Iron ore, Gold, Nickel and Uranium. Therefore, the big powers have set eye on the Arctic, including the US; Russia and China, with ambitions to dominate which may be termed as The Arctic Great Game.

Strategic location of the Arctic

“Whoever holds Alaska will hold the world”, General Billy Mitchell was not wrong when he uttered this phrase in 1935. Indeed, during the Cold War, the possession of Alaska for the US, its only in the Arctic, proved fruitful. American early warning satellites and missile defenses were installed in Alaska to detect Soviet infiltration. The Cold War is over now, but the competition over the Arctic has reinvigorated. The US, under Trump administration, is ambitious to dominate

the Western Hemisphere. The Arctic, especially Greenland, can be defined as the head of the Western Hemisphere. The geographical position of the Greenland is indeed enviable. East of it runs the widest gap between the Arctic and the Atlantic Ocean. Therefore, America holds the Island in esteem for its strategic location. The 2026 National Defense Strategy emphasizes the US military and commercial access to the Arctic, especially Greenland. It already operates the Pituffik Space Base (formerly Thule Air Base) in Greenland, in addition to its Alaskan military bases in the Arctic.

Russia, an important stakeholder in the region, enjoys one of the longest coastlines and largest territories in the Arctic. Russian activities in the Arctic are not novice. In the late 18th century, Russian emperor Peter the Great launched the ‘Great Northern Expedition’ which aimed to search for a northern sea route that could connect the Pacific and Europe. The quest for a such a sea route seems promising now as the Arctic waters become traversable. In 2020, Russia unveiled its Arctic policy till 2035. Among others, it emphasized the development of the Northern Sea Route (NSR) as ‘a national transport communication of the Russian Federation that is competitive on the world market’. However, after Russian invasion of Ukraine, Kremlin adopted a staunch outlook. In Feb 2023, Putin decreed to amend the country’s Arctic policy. The amended document mentioned the prioritization of the national interests of the Russian Federation in the Arctic. For this purpose, Russia has endeavored to transform NSR into a global trade and energy route. Russia currently operates the largest Icebreaker fleet and thanks to this technology, the transit of trade vessels is expected to increase through the NSR.

Routes through the Arctic Ocean. Source: Author’s creation

However, any unilateral Russian action in the Arctic Ocean would not land off the attention of the other Arctic states. While Russia is ambitious to hew the Arctic Ocean as a “Russian Lake”, the other Arctic countries too deem the Arctic as their ‘number one priority’. The Nordic countries consider the Arctic as a security concern, they also see Russia as a threat in the region while emphasizing sustainable development in the region. Therefore, the strategic competition in the Arctic will, inevitably, shape the European security dynamics.

The strategic importance of GIUK (Greenland-Iceland-UK) Gap, a body of open water between the three countries, is still relevant. During the Cold War, it provided the Soviet vessels an outlet into the North Atlantic Ocean which conferred optimal range to strike NATO targets. However, in late 2019, Russian submarines surged through the gap into the North Atlantic in what was a large-scale military exercise to which NATO forces counteracted with air missions to gather reconnaissance. Therefore, the Arctic is of strategic significance. It acts as a vanguard for the defenses of the Americas and Europe.

The most interesting case offered in the Arctic security is that of China, which lacks any geographical connection to the region. For Beijing, the Arctic begets new opportunities. China has already declared itself a “Near-Arctic State” in its Arctic Policy 2018 and seeks to participate in the development of the Arctic shipping routes. China’s growing interest in the Arctic shipping routes can be interpreted as its efforts to diversify its trade routes. Compare the two routes which link China to the Western European markets: First is from the Chinese ports through the East and South China Sea, into the Indian Ocean, then crossing the Suez and reaching Mediterranean, squeezing through Gibraltar strait and reaching destinations. China’s apparition, utilizing this route, is evident in what has been translated as the “Malacca dilemma”. The second runs northerly from the Chinese ports and then cruising along the Arctic reaches Northern and Western Europe. The first is long, time-consuming and precarious in case of conflict given complex maritime features of the region. The second not only cost saving but also relatively more secure and safe. Therefore, the prospects for China to make the Arctic a “Polar Silk Road” are rewarding.

| Probability of expansion of power in the Arctic of US, Russia and China | |||

| Political | Military | Economic | |

| United States | high | medium | high |

| Russia | high | high | high |

| China | medium | low | high |

Future Power Politics in the Arctic. Source: Author’s creation

The Race to Secure the Arctic Resources

President Trump, during his first term, had tried to buy Greenland. However, his efforts were reinvigorated after his re-election in late 2024. During his second term, he has repeatedly threatened to occupy Greenland by using military force, the island defined by him as a matter of national security. The strategic importance of the Greenland is evident. Trump’s interest in the Greenland can be defined by two reasons. First to oust China and Russia from the region who have been increasing their influence in the region, as he perceives. Secondly, Trump wants to secure the resources of the Greenland for the US. Greenland, as said earlier, is rich in rare-earth minerals, which have their application in military industries, medical equipment, oil refining and green energy. Currently, China is the largest exporter of the rare earths. US deems ramping up its rare earth’s resources crucial for countering the Chinese monopoly over them. Last year, a global supply chains crisis loomed following China’s restrictions on the exports of the critical minerals. Moreover, to meet the threat imposed by climate change, the real progenitor of the shift in Arctic security, the transition to renewable and smart energy sources demands sufficient mineral resources including the rare earths. These are used in wind turbines and electric vehicles.

Russia extracts a huge amount of its energy and mineral resources from the Arctic. It produces rare earths, nickel and cobalt from its Arctic territory. Russian Arctic also holds almost 37.5 trillion cubic metres of natural gas, 75% of Russia’s gas reserves. As the permafrost thaws and the sea ice melts in the Arctic, Russia will expand its efforts to secure the resources in the region. Therefore, the Kremlin keenly observes changing environmental and political dynamics in the Arctic.

Lastly, the ‘Near-Arctic State’ has also augmented its footholds in the Arctic. China has invested in economic sectors in the Arctic. It is yet to be unveiled whether China’s ambitions in the Arctic are solely for peaceful economic purposes or rather they embody a strategic objective. So far, China has remained innocuous, focusing on economic ties with the Arctic states which benefit all.

Conclusion

The Arctic is going to witness a tense geostrategic competition. Climate Change has transformed this previously unnoticed region into a new stage of strategic competition. Arctic routes and resources invite regional as well as extra-regional powers to vie for dominance in the high north. Therefore, states have shifted their focus to the Arctic. The political and strategic facts imply that in the future the master of the Arctic will decide the matters of the world.