Displaced Survivors of Kwara Massacre Recount a Night of Terror

Hauwa Abdulkarim was inside her house when the violence began.

As evening settled over Woro, a village in Kaiama Local Government Area (LGA) of Kwara State, North Central Nigeria, on Feb. 3, the terrorists descended on motorcycles like a sudden storm. What began as a seemingly ordinary evening quickly turned into chaos, with about 170 people killed, their homes set ablaze, celebrations interrupted, and families forced to flee.

“Most of the youths were at the field playing football [on a school field close to the house]. Then we saw people running back home with the news that kidnappers had entered the town,” Hauwa recounted.

At first, she did not panic. The terrorists had sent word days earlier, a letter to the district head saying they were coming to “preach”. When the motorcycles rolled in, there was confusion and fear.

Then the shooting started.

“Upon entering the village [around 5 p.m.], they started shooting at people,” she said. The football field emptied in seconds. Inside her house, Hauwa and her husband tried to gather their children, counting them quickly and realising some were still outside.

“We were thinking about some of our children who were outside and those that went to the football field. The shooting continued until 5 a.m., the next day,” Hauwa added.

But the terror was not continuous. It came in waves.

“When it was time for the call to prayer, they suddenly stopped,” she recalled. “They made the call to prayer for Maghrib and called out people to pray.”

The silence was almost as frightening as the gunfire. After the prayer, the shooting resumed. “They did the same for the late-night prayer, stopping briefly to make the call to prayer and observe it. Afterwards, they resumed shooting through the night,” Hauwa told HumAngle.

Later that night, everything suddenly became quiet: the gunshots stopped. That was when the residents began to hear the call to come out and extinguish the blazing fires.

Many were confused and afraid, unsure whether to come out to help put out the flames, flee, or stay hidden.

Hauwa and her husband came out with other residents, but they were ambushed. “We thought they had gone, so we came out with buckets to save our homes. That was when they opened fire again. It was a trap and my husband was almost killed in that encounter. He hid in a ditch, as I ran inside to stay with my children,” she recounted.

By dawn, the village was scarred by destruction — dead bodies with gunshot wounds to the head and cuts to their necks, houses reduced to ashes, the district head’s residence consumed by fire, and families shaken by the night’s events.

The alternating rhythm of violence and prayer created a chilling atmosphere that has left Hauwa to grapple with both physical loss and psychological trauma. She described the ordeal as a mix of terror and deception, designed to lure people into vulnerability.

The attack on Woro and neighbouring Nuku communities has displaced at least 941 persons and exposed glaring intelligence failures, despite prior warnings, and the growing influence of terror groups operating from the Kainji Lake National Park axis. HumAngle met with some of the survivors in Wawa, a town in nearby Niger State.

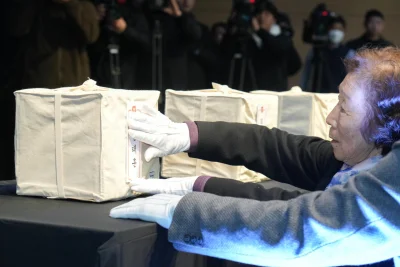

Ibrahim Ismail Dan’umar, a community leader in Wawa who serves as the coordinator of the displaced persons, told HumAngle that the community has been providing the families with relief materials and accommodation, as there is no designated camp for them.

“On our records, we have people from Plateau, Nasarawa, Kebbi, Kwara, and Niger,” he noted. “We decided to organise a breakfast for them and announced that anyone offering shelter to the displaced should bring them to the gathering. On the first day, we had 381 people, even though we only projected for 200.”

“The next day, we distributed food items, and by the third day, the Emir of Borgu and representatives of Kaiama Local Government came with support, which we shared among them. Now, we have 941 displaced persons — adults and children — here in Wawa,” he explained.

Amnesty International, a global human rights organisation, described the killings as evidence of systemic neglect of rural communities. In a statement, the organisation condemned the attacks as “vicious” and criticised the Nigerian government for leaving rural communities at the mercy of rampaging terrorists.

Following the deadly attacks, the Nigerian military has formally launched a multi-agency offensive in Kwara and Niger states, code-named ‘Operation Savannah Shield’, designed to dismantle terrorist networks and restore security in the region.

The initiative was flagged off on Thursday, Feb. 19 at Sobi Barracks in Ilorin by the Chief of Defence Staff, General Olufemi Oluyede, the Chief of Army Staff, Lieutenant General Waidi Shaibu, and the Kwara State Governor, AbdulRahman AbdulRazaq.

Unmasking those behind the terror

This attack is one of the deadliest this year.

In the weeks leading up to the Woro massacre, Sadiku’s faction of Boko Haram had already reached out to the community.

According to the village head, Salihu Umar, a letter dated Jan. 8 — written in Hausa and bearing the signature of JAS (Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’adati wal-Jihad) — was delivered to him. The message requested a “private” meeting with local leaders for preaching and assured residents that no harm would come to them.

Umar said he made copies of the letter and forwarded them to both the Kaiama Emirate and the Department of State Services (DSS) office in Kaiama. Despite this warning, no preventive measures were taken, raising questions about Nigerian security intelligence.

However, security sources revealed that the killings are part of a jihadist campaign commanded by Malam Sadiku, a notorious terrorist whose influence has steadily expanded across multiple parts of Nigeria’s North Central region.

HumAngle has extensively documented how Sadiku, once closely aligned with Boko Haram founder Muhammad Yusuf and later Abubakar Shekau, has re-emerged at the forefront of a dangerous wave of insurgency.

After a stint with the Darul Islam sect, he returned to Boko Haram with renewed zeal, positioning himself as one of Shekau’s most loyal comrades. Sadiku’s financial windfall from the infamous Kaduna train abduction gave him the means to expand his influence, strengthen his network, and spread Boko Haram’s radical ideology across Niger State and neighbouring states.

With resources and reputation firmly behind him, Sadiku built a growing base of followers and fighters. Under his leadership, extremist teachings were not only revived but embedded into local communities, turning quiet rural villages into recruitment and indoctrination centres.

His trajectory, security analysts such as Yahuza Getso of Eagle Integrated Security note, reflects a long-term strategy of territorial control and ideological entrenchment, with this latest attack underscoring both the scale of his operations and the devastating impact on local communities.

But he is not alone.

Malam Mahmuda, the leader of the Mahmudawa (an Ansaru faction), has also turned the Kainji Forest into a safe haven for his fighters. Despite previous arrests of their leaders, the group has replenished its ranks and rearmed its foot soldiers.

According to Ahmad Salkida, HumAngle’s founder, who is one of the foremost experts on the protracted Boko Haram insurgency and the complex conflicts in the Lake Chad region, “The relocation of Sadiku and Umar Taraba, both veteran jihadist operatives, to the Kainji axis in 2024 marked a shift. Their presence injected technical expertise into a space previously dominated by loosely organised armed groups.”

He added that they are fragmented into smaller camps: some closer to the Benin border, acting as brokers linking criminal networks of jihadist actors. The Mahmudawa are said to facilitate training, arms movement, ransom negotiations, and sanctuary for fighters arriving from outside the region.

“Official claims regarding the arrest of their leader, Malam Mahmuda, remain unconfirmed in border communities, where continued attacks and coordinated leadership are still attributed to the group,” he noted.

“If the Mahmudawa are brokers, the Lakurawa are enforcers. With an estimated 300 fighters, they have become one of the most active jihadist–terrorist hybrids affecting […] border communities. Operating from within and around Kainji Lake National Park, they routinely launch incursions into Bagudo and Suru LGAs, combining attacks on military targets with ideological messaging aimed at delegitimising the Nigerian state.”

Security sources and community accounts indicate that Sadiku’s group and Mahmudawa, linked to jihadist networks across West Africa, have long operated in the dense Kainji Lake National Park and Borgu Reserve, straddling Niger and Kwara states. According to the sources, this is an attempt to create another Sambisa: a hotbed for Boko Haram in the North East.

Local residents have repeatedly warned authorities about the presence of terrorist camps in the forest, but responses have been slow. Between September and December 2025, the Federal Government carried out aerial and ground operations in the area, yet the group remains influential. The forest’s vast terrain and porous borders have provided cover for training, recruitment, and staging raids.

Getso believes that Sadiku’s Boko Haram has rebranded and reorganised remnants of Ansaru and JNIM cells, consolidating them into a formidable force in North Central Nigeria. He also revealed that the Woro massacre underscores the growing threat posed by Sadiku’s network.

“Nigeria’s current counter-terrorism strategy is insufficient. There is a need for a comprehensive review of military doctrine and intelligence operations,” Getso noted.

A dream on hold

At just 22 years old, Ibrahim Ishaq Woro had recently graduated from the School of Health in New Bussa, Niger State. He had only returned home to Woro a year earlier and was in the process of applying for jobs when the attack shattered his community.

On the day of the assault, Ibrahim was sitting at a tea stall when he spotted the terrorists approaching. Recognising them from a previous encounter, he fled — but minutes later, gunfire erupted across the village.

That day was meant to be joyous, with three weddings taking place, including his cousin’s. Instead, the celebrations turned into a massacre.

“The wedding was taking place at our house. Yahaya, my cousin, was killed. His wife and children were abducted and taken to the forest,” Ibrahim recalled.

Like Hauwa, who described how false calls to prayer lured residents into ambushes, Ibrahim witnessed the same deception. “Those who hid inside were warned: ‘you either come outside or burn in your houses.’ Those who opened their doors out of fear were kidnapped,” he said.

By dawn, Ibrahim returned to find the bodies of women, children, and men scattered across the community. His closest friends — Zakari, Habib, and Shamsudeen — were among the dead.

His mother, three siblings, and several family members who came for the wedding were taken captive. “Personally, we lost 20 people from my extended family and about 50 are still missing,” he said quietly, while looking away.

Like Hauwa, Ibrahim and other survivors fled Woro to Wawa and other neighbouring communities, with their belongings in wheelbarrows and on their heads, trekking for about 42 kilometres with swollen feet in search of refuge.

Now displaced, their only plea is for the government to secure the release of kidnapped women and children, and restore safety so families can return home.

“For those we have lost, we can only pray for eternal peace. But we need our loved ones back. That is why we are afraid to even return home,” Ibrahim said.

Officials in Wawa town, speaking on condition of anonymity, said discussions are ongoing with the district head to facilitate the safe return of displaced residents. The move, they explained, would allow survivors to access federal and state-level interventions more effectively once back home.