A Cotswolds local has shared her five favourite spots to go for a bite to eat when you’ve completed your long country walk and need something hearty and delicious

Who can resist a hearty pub lunch after a refreshing walk, soaking up the stunning natural beauty around them? It’s simply an unbeatable experience.

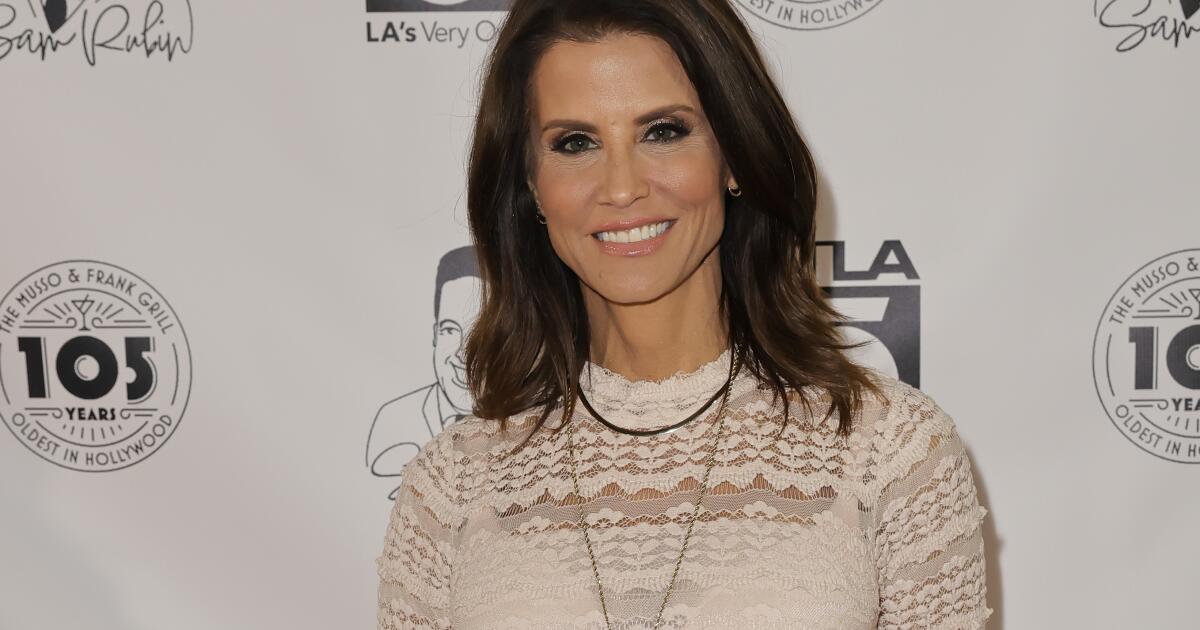

It feels like a well-earned treat, and there’s nothing quite like the satisfaction that comes after a good bout of exercise. That’s why a local woman from the Cotswolds has shared her top picks for a pub lunch if you’re visiting the area, but she warns that you “must” book in advance to avoid disappointment. Ali listed five of her favourite local eateries, all of which sound absolutely delightful and are worth checking out sooner rather than later.

1. The Kingham Plough, Kingham

Ali enthused: “My all-time favourite pub in the Cotswolds. Incredible roasts, consistently great food, faultless service and one of the prettiest villages around.”

A recent Tripadvisor review reads: “We had a lovely dinner with family and friends. The food, especially the more sophisticated dishes, was very good, the ambience pleasant, and the service enjoyable.”

2. The Lamb, Shipton-under-Wychwood

“Outstanding food and such good value evenings (think chicken night, curry night, etc). They also own a few other brilliant Cotswolds pubs that are just as good,” Ali noted.

A recent Tripadvisor review reads: “Roast Chicken – best I’ve ever had (obviously apart from my wife’s and mother’s). It’s really very exceptional. I would go as far as saying I would travel to the Lamb just to eat the roast chicken. Fabulous deal on Thursdays – an entire roast chicken plus trimmings for £30.”

3. The Fox at Oddington, Oddington

Ali praised it, writing: “A Daylesford-owned pub and a local favourite – especially on Thursday nights. Amazing pizza, beautiful interiors and a great atmosphere.”

One glowing Tripadvisor review gushed: “Wow! What a pub… the vibes are on point as soon as you walk in the door. We went on a busy Friday evening without a booking, and after having a drink in the bar, we were seated at a table by James, who was an outstanding host!”

“The food was absolutely superb, we had steak tartare, and the nduja scotch egg for starters, both amazing, then had the Fox double burger and beef bourguignon.

“Hands down the best burger I have ever tasted, and the beef was amazing, both were generous portions, great value for money. The service was great the whole time. Shout out to James, who was great to chat with and looked after us!”

4. The Bull, Charlbury

Ali described it as: “Recently named one of the best pubs in the UK. The menu might look a little intimidating, but trust me – the food is fantastic. Pie night every Thursday.”

One Tripadvisor reviewer shared: “We had a great lunch at The Bull! It is somewhat full of Londoners in rust-coloured corduroy, but that didn’t spoil what was a lovely lunch!”

“You do need to book as it’s extremely popular. Be prepared that it is incredibly dark with only candles for lighting, but all in all, we had a lovely meal – the plates are small, but deceivingly filling! The staff are really nice, and the atmosphere is cosy, lighthearted and easy.

“One word of caution – if you order a Bloody Mary, it may blow your head off!”

5. The Chequers, Churchill

Ali said: “Clarkson’s local and currently undergoing a refurbishment. Reopening mid-March in a stunning village location – one to watch for great food and atmosphere.”

A recent Tripadvisor review reads: “We had a lovely meal at The Chequers. The food was genuinely excellent – fresh, well-cooked, and full of flavour, with a great menu choice. What really stood out, though, was the staff. They were incredibly attentive without being overbearing, friendly, and made us feel very welcome throughout our visit.

“Everything came out promptly, and nothing was too much trouble. It’s clear they really care about the quality of both the food and the customer experience. We’ll definitely be returning and would happily recommend The Chequers to others.”

Which pub would you fancy visiting if you found yourself in the Cotswolds? Share your thoughts in the comments below…