L.A. County seeks to change law behind billions in sex abuse payouts

At a luncheon this week for L.A. County politicos, Supervisor Kathryn Barger pitched what she framed as a commonsense reform.

Legislators in Sacramento, she argued, need to change a 2019 law that extended the statute of limitations for sex abuse lawsuits, opening the floodgates for decades-old claims that have cost the county nearly $5 billion and counting in payouts.

“I want them in Sacramento to fix it,” she said. “I have to believe that we are the tip of the iceberg.”

The controversial law, Assembly Bill 218, has led to thousands of claims over abuse that took place in schools, juvenile halls and foster homes. Supporters say it continues to give survivors a chance at justice, while Barger and other officials warn the cost of the litigation is driving local governments to the brink of bankruptcy.

Rolling back AB 218, critics argue, is the single most obvious thing state lawmakers can do this legislative session.

The push has gained momentum amid concerns of fraud in the first of two payouts approved last year by L.A. County officials. At $4 billion, it was the largest sex abuse settlement in U.S. history, with the money set aside for more than 11,000 victims.

The Times reported last fall on allegations of fabricated claims filed by plaintiffs within the settlement, which prompted L.A. County Dist. Atty. Nathan Hochman to open an investigation. Hochman told the supervisors this week that his office is reviewing “thousands of claims” for fraudulent submissions and predicted savings in the “hundreds of millions if not billions of dollars.”

Speaking at the event Wednesday, Barger suggested capping attorneys fees — acknowledging that some high-powered attorneys in the room were involved in the county’s litigation.

Out of the $4-billion payout, she said, “about $1.5 billion will go to attorney fees — present company included.”

Barger referenced a former state Assembly speaker known for bare-knuckle tactics, which she said were needed now in the Capitol.

“If Willie Brown were up there, I’m sure he’d lock everyone in a room and slap some sense into them at this point,” she said.

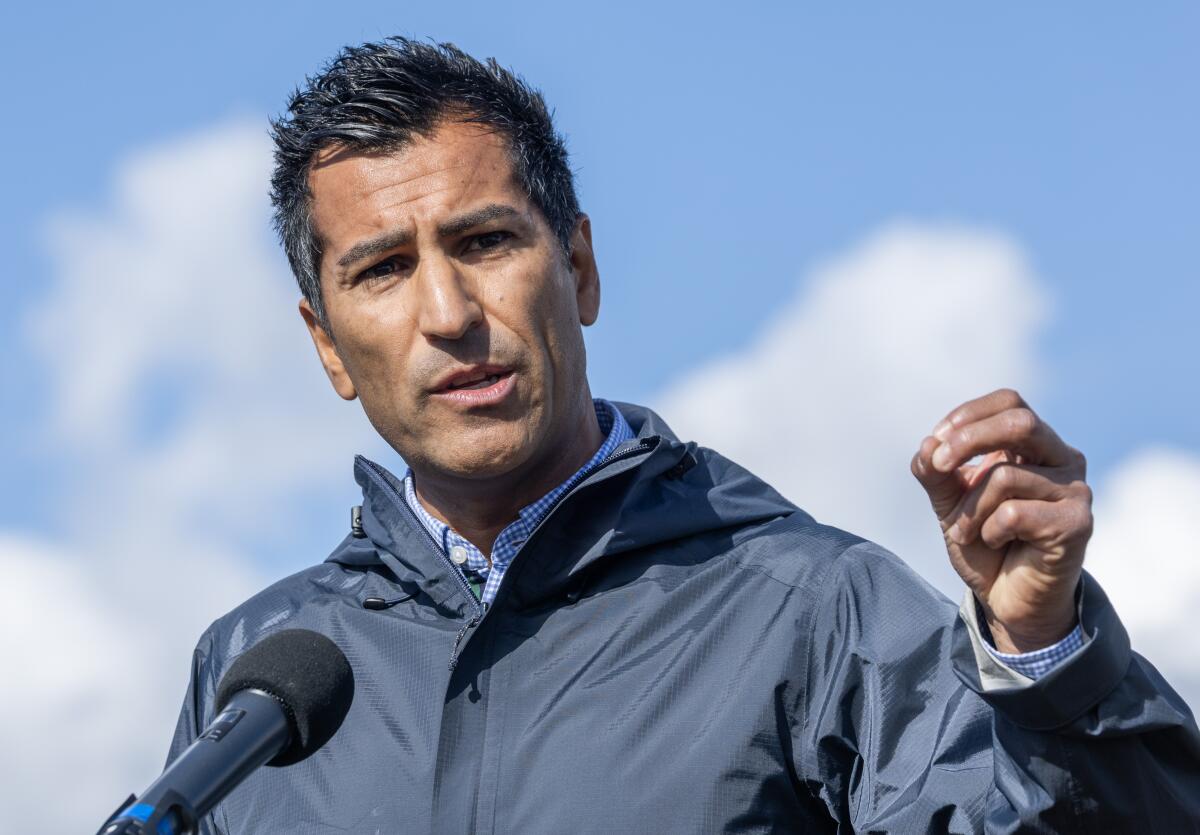

Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas has asked California legislators to consider changes to AB 218. Critics say sexual abuse lawsuits are driving local governments to the brink of bankruptcy, while supporters say it is one of the few ways for victims of abuse to get justice. Rivas spoke in Ventura County on Nov. 18, 2025.

(Myung J. Chun / Los Angeles Times)

This session, Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas has assigned a group of legislators to look at what changes might be made to the law.

A spokesman for Rivas, Nick Miller, said the goal is to provide “meaningful access to justice for all survivors” without forcing service cuts in schools and governments.

“There is a group of members discussing possible solutions that strike the right balance on this critical issue,” Miller said.

It’s a tightrope walk that no legislator has mastered.

Sen. Benjamin Allen (D-Santa Monica), who tried last year to increase the burden of proof for these cases, was branded a protector of predators.

Sen. John Laird (D-Santa Cruz) got further with a pared-down bill only to watch it blow up last session over concerns he was trampling on victims’ rights.

“I worked hard to strike the middle ground,” Laird said. “It just was too hard.”

Organized labor, a powerful voice in Sacramento, could sway the equation. County unions said they were told repeatedly at the bargaining table last year that they couldn’t get raises because of the massive sex abuse settlements, potentially setting them on a collision course with victim advocates.

Lorena Gonzalez, who wrote AB 218 in 2019 before leaving the Legislature to head up the California Federation of Labor Unions, said lobbying firms had been urging unions recently to take the lead on convincing the Assembly to change the law. The union leaders have yet to take a stance, she said.

“Although there’s some desire to especially fix what happened in L.A., there wasn’t an overwhelming desire to roll it back,” she said.

While serving in the state Legislature, Lorena Gonzalez authored AB 218, a state law that extended the statute of limitations for lawsuits over sexual abuse in government facilities. Gonzalez, now with the California Labor Federation, spoke at Balletto Vineyards in Santa Rosa, Calif., on April 26, 2024.

(Jeff Chiu / Associated Press)

A Times investigation last fall found nine clients of Downtown L.A. Law Group, a law firm that represents thousands of plaintiffs in the county’s largest settlement, who claimed that recruiters had paid them to sue. Some clients said they were told to make up stories of abuse that became the crux of their lawsuit.

The firm, also known as DTLA, has denied paying any client to sue. Andrew Morrow, the main attorney on the cases for DTLA, argued in a Feb. 13 court filing that the recent subpoena by the State Bar seeking their court records as part of an investigation into the firm amounted to an “ill-advised fishing expedition.” The firm argued that allowing the State Bar to review its filings violates clients’ privacy.

“No one disputes that these allegations are troubling and, if true, serious,” Morrow wrote. “However, untested allegations printed in a local newspaper — no matter how compelling — do not override the privacy rights” of victims.

Assemblymember Dawn Addis (D-Morro Bay), a longtime advocate for sex abuse survivors who vehemently opposed the last attempt at changing AB 218, said that “there’s all kinds of discussions about potential solutions” for fraud underway in the Legislature.

But limiting victims’ ability to sue, as some have called on lawmakers to do, is a clear no-go, she said.

“Silencing victims is not the way to get out fraud,” she said.

Like many legislators, she pinned some of the blame for the alleged fraud on poor vetting by lawyers for L.A. County. The county has said the cost of taking depositions for more than 11,000 cases would be “astronomical,” and that no records exist for many of the older cases, leaving them defenseless.

In a statement to The Times, a spokesperson for the L.A. County counsel’s office said the Legislature created AB 218 “without a single safeguard against fraud.”

“That is their failure to own,” the statement said. “This is the system the Legislature built, and they need to fix it.”

The county maintains it is not trying to squash victims’ rights, but rather keep vital services — pools, parks, health clinics — open.

“I am tired of whenever a government official stands up and says, ‘Hey, there needs to be some reform here,’ that we’re accused of victim blaming, pedophile protecting,” says Joseph Nicchitta, the county’s acting chief executive.

After agreeing to the $4-billion payout in April, county officials opted into a second $828-million settlement in October covering an additional 400 cases. Since then, more than 5,000 cases have been filed that are not part of either settlement and still need to be resolved.

“Let me tell you what will not work for L.A. County,” Nicchitta said. “The nibbles around the edges — ‘Make the procedure a little tighter, we’ll require a couple more documents.’”

He said he believes the Legislature needs to weigh the need to pay survivors against the obligation to keep the social safety net intact. One solution, Nicchitta said, could involve a victims compensation fund that would eliminate the need for someone to hire an attorney in order to submit a claim and receive money.

“Acknowledge the harm, provide real competition, [and] do it fast,” he said. “You don’t need a lawyer.”

John Manly, a lawyer who has represented sex abuse survivors for more than 20 years, sits at his law office in Irvine on Dec. 29, 2023.

(Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

After getting flooded with sex abuse claims related to juvenile facilities following a similar change in the statute of limitations, Maryland capped sex abuse cases against government entities last year at $400,000 and limited attorneys’ fees to 25% for cases resolved in court.

For many California trial attorneys, ideas such as these are nonstarters.

“The reason they’re proposing a victims’ fund is they continue to know that those people don’t have any political power,” said John Manly, a veteran sex abuse attorney who is part of the second L.A. County settlement. “The only power they have is to hire a lawyer and get justice.

“We’re going to fight,” he said.