3 Los Angeles night hikes to check out during Ramadan

Many of us go into the mountains to think and practice gratitude.

For the hundreds of thousands of Muslims across Los Angeles County observing Ramadan this month, spending time in nature can offer an opportunity for quiet reflection and growth.

“This sacred month provides an opportunity to merge the spiritual with the physical, finding solace and inspiration in nature,” nonprofit Muslim Outdoor Adventures notes. “Through mindful hiking, we aim to embrace the challenges of staying active during Ramadan, using the trails as a space for reflection and collective growth.”

Ramadan is considered the holiest month of the Islamic calendar. The holiday typically lasts 29 or 30 days, and during that time, Muslims will fast from sunup to sundown, including not drinking water. This excludes those who are exempt from fasting or not observing the holiday.

This year’s Ramadan started in mid-February and will end around March 19. (The Islamic calendar is based on lunar events, so Ramadan’s start and end dates vary from year to year.)

For fasting hikers, it’s important to ensure you plan accordingly, given your limited daily water and food intake.

Nadiim Domun, materials engineer at INOV8, said in a blog post that fasting hikers should plan ahead, and if they feel up to it, plan to break their fast at the top of a hill, taking their time to arrive at sunset. “On some days you’ll feel better than others. Be kind to yourself and only go hiking on days when your body feels up to it,” Domun said.

Below you’ll find three hikes and walks in places open after sunset. If observing the holiday, may your fasting be easy. Happy Ramadan!

A view of the Griffith Observatory with downtown Los Angeles in the background.

(Wally Skalij / Los Angeles Times)

1. Crystal Springs – Atwater Park in Griffith Park

Distance: 2.7 miles

Elevation gained: 130 feet

Difficulty: Easy

Dogs allowed? Yes

Accessible alternative: Los Angeles River Bike Path

The Crystal Springs – Atwater Park route is a 2.7-mile easy stroll through the southeast side of Griffith Park that includes a quick side trip over the L.A. River.

Griffith Park is open from 5 a.m. to 10:30 p.m., although you’ll want to mind where you park, as some areas are open only until sunset.

To begin, you’ll take the wide dirt Main Trail north for just over half a mile before reaching a tunnel. Congrats! You’ve just completed the hilliest portion of this hike. It’s time to turn on that headlamp as you take the tunnel beneath the 5 Freeway, marveling at the wonders of human ingenuity.

Next, you’ll head over to the North Atwater Bridge, or La Kretz Bridge, an impressive modern design you’ve probably noticed from your car in gridlock traffic.

The North Atwater Bridge, or La Kretz Bridge, over the L.A. River.

(Emil Ravelo / For The Times)

The route next takes you to North Atwater Park. This area was separated from the rest of the park when the 5 Freeway was built in the late 1950s, resulting in 200 “prime acres of parkland” being destroyed, according to Friends of Griffith Park. Perhaps you’ll notice the squawk or chirp of birds settling in for the night.

From here, the path loops around the area for about a third of a mile before taking you back to the bridge. You’ll pass a corral and interpretive signs, among other things.

After crossing back over the bridge and under the tunnel (headlamp!), you’ll have a clear view of Beacon Hill, another great hiking destination in the park that offers stunning views of downtown L.A. You will head north again on the Main Trail, walking parallel to the 5. Hopefully the sound of the freeway is blocked by the lush trees that line the path.

You’ll take the Main Trail for about a third of a mile. At 1½ miles in your hike, you’ll bear left (or west), passing the Anza Trail Native Garden, planted by volunteers using seeds harvested from the park.

You’ll loop southwest around the path, passing the golf course and a baseball field before arriving at the newly renovated Griffith Park Visitor Center, open daily from 8 a.m. to 7 p.m. (It also has restrooms!)

From the visitor center, you’ll head east along a dirt path before looping back up with the Main Trail, which you’ll take south back to your car.

If you’d like something a little more challenging, you can peruse the Griffith Park Explorer route options. One of my favorites is the Five Points – Beacon Hill loop.

And if you’d like to go with a group, L.A. City Department of Recreation and Parks’ junior ecologist Ryan Kinzel and Emerson College professor Jacob Lang are hosting a free night hike through Griffith Park this Thursday.

So grab your headlamp, and have a great time!

Louisa McHugh, of San Pedro, jogs at Cabrillo Beach.

(Carolyn Cole / Los Angeles Times)

2. Beach path at Cabrillo Beach

Distance: 1.6 miles

Elevation gained: Minimal

Difficulty: Easy

Dogs allowed? No

Accessible alternative: The route below is a paved flat path.

This 1.6-mile beach walk is a gentle stroll along the mile-long Cabrillo Beach, where during the day you might spot kite surfers, barges and Catalina Island in the near distance.

To begin, start your walk in the northeast corner of the parking lot where the sidewalk begins. Walk south down the sidewalk, unless you’d like to walk on the sandy beach instead. Near the Cabrillo Beach Bath House, the path will curve east. You’ll continue east along the jetty until you reach the Cabrillo Beach Pier, where you might spot people fishing. You can pause to take in the views for as long as you’d like before heading back.

Although there are many beach walk options in Southern California, the reason I’m recommending Cabrillo Beach is because it’s a great place to observe grunion runs. At night, these small silvery fish come completely out of the water to lay their eggs in the wet sand, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Beachgoers witness an unusual fish spawning ritual known as a grunion run on Cabrillo Beach in San Pedro.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times)

“Grunion make these excursions only on particular nights and with such regularity that the time of their arrival on the beach can be predicted a year in advance,” according to the agency.

Depending on how late you’d like to stay up, you can take a beach walk and stay for the grunions, which are expected to arrive at 10:25 p.m. Thursday and 10:50 p.m. Friday.

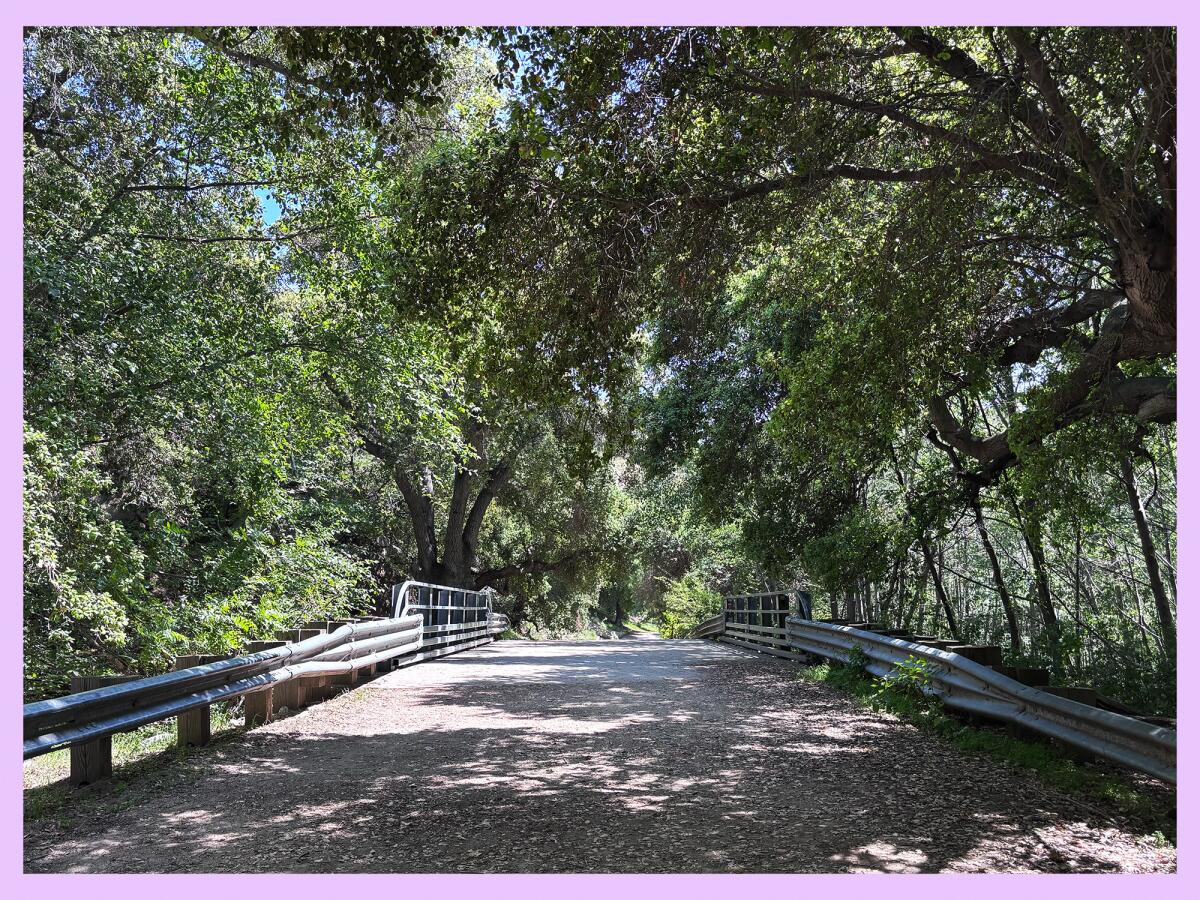

Hikers walk down a path at Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area.

(Kayla Bartkowski / Los Angeles Times)

3. Gwen Moore Lake to Western Ridgeline in Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area

Distance: Around 2½ miles

Elevation gained: About 300 feet

Difficulty: Moderate

Dogs allowed? Yes

Accessible alternative: Gwen Moore Lake path

This 2½-mile journey through Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area will take you past a charming lake and will gain just enough elevation to provide you with striking views of the city. It is more challenging than the other two paths, so please plan accordingly. (And pack that headlamp!)

Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area is open from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday. The park is around 330 acres and includes the stunning Baldwin Hills Scenic Overlook, which thousands access every year via a straight staircase with 282 steps.

Upon arriving at the park, you’ll pay $10 to park. Ask the staff member at the toll booth whether they have a map, as it’s great to have one on hand as you hike. For this hike, I’d recommend parking near the Gwen Moore Lake if you can.

To begin the hike, you’ll start at Gwen Moore Lake. You can either take the paved path that takes you along the western side of the lake or the straight paved path on the eastern side of the lake. It will take you due south.

About a third of a mile in, you’ll walk east past the Kenneth Hahn Visitor Center before quickly joining with the Park to Playa Regional Trail, a 13-mile path that guides hikers from near Windsor Hills to the ocean (near Ballona Creek). That’s an adventure for another day!

You’ll take Park to Playa, a short jaunt, bearing left (northwest) toward a large green space to join the Bowl Loop Trail, or on some maps, Park to Playa Alternate. Follow this path in the northerly direction until it jags left where you’ll join the Western Ridgeline Trail (or Park to Playa Alternate, depending on your map). From here, say hello to beautiful views of the city!

You will next take Diane’s Trail (who is she?) just over half a mile before heading down via the Forest Trail. Pause along the way to appreciate more gorgeous views of the city, including of downtown L.A.

Head south past the Japanese garden, and then take the paved road from the Japanese garden back to where you parked, hopefully near the lake.

3 things to do

During a previous Dana Point Festival of Whales, guests attend a sacred ceremony given by the Acjachemen Nation and observe the Dana Point Surf Club as their members paddle out to welcome the whales to Dana Point’s shores.

(Dana Point Harbor)

1. Whale-come the cetaceans in Dana Point

The 55th Annual Dana Point Festival of the Whales, which celebrates gray whale migration, is scheduled for Friday through Sunday in Dana Point Harbor. Visitors can attend the “Welcoming of the Whales” ceremony at 4:30 p.m. Friday at the Ocean Institute, or on Saturday, observe the cardboard boat race, learn at the marine mammal lecture series or chow down at the clam chowder cookout. On Sunday, attendees will pick up trash at 9 a.m. near at the Richard Henry Dana Jr. statue before attending a concert from noon to 5 p.m. performed from a floating dock. Learn more at festivalofwhales.com.

2. Stand up for public lands in Ventura

Environmental advocacy groups Los Padres ForestWatch and Climate First: Replacing Oil & Gas will host a hike at 11 a.m. Sunday through the Harmon Canyon Preserve in Ventura. Group leaders will educate hikers on the Trump administration’s proposal to open 850,000 acres, including about 400,000 acres across Central California, to oil and gas drilling. After the hike, participants are invited to make posters to spread awareness of the threat to public lands. Register at eventbrite.com.

3. Kick back with a kite in Redondo Beach

The 52nd Annual Redondo Pier Kite Festival will take place from noon to 5 p.m. Sunday at the Redondo Beach Pier (100 Fishermans Wharf). This free community event will feature live music, face painting and a kite flying contest. Kites will be available for purchase on the pier while supplies last. Guests can also bring their own kites. Learn more at redondopier.com.

The must-read

Visitors take the chair lifts at the Mt. Baldy Resort.

(Christina House / Los Angeles Times)

The ski world is becoming increasingly owned by large corporate chains, but small shops like the Mt. Baldy Resort continue to hang on. Times staff writer Jack Dolan wrote about how Mt. Baldy Resort, just over an hour from downtown L.A., works hard to remain competitive. The resort offers a quick escape for Angelenos who want to ski and appreciate “the wide expanse of the Inland Empire stretched to the Pacific Ocean nearly two vertical miles below,” Dolan wrote. Many of its guests find its old-school style more welcoming than the ritzy lodges in Taos and Tahoe. “There’s big conglomerates trying to buy everybody up, and I don’t want that,” said Chris Caron, a 65-year-old retiree who lives 20 minutes down the road from Mt. Baldy Resort. “That’s what I love about here. It’s not so commercialized.”

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Porkchop is free! A month ago, I featured a story by Times staff writer Lila Seidman, introducing Wild readers to Porkchop, a three-flippered sea turtle who was being rehabilitated by the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach. “Many Angelenos don’t know Eastern Pacific green sea turtles are swimming in their proverbial backyard, but they are — and they’re thriving,” Seidman wrote. “It’s estimated that about 100 of the hulking-yet-graceful animals live in the lower stretch of the San Gabriel River, where salt and freshwater commingle.” And thankfully, it’s now about 101, as Porkchop was released back into the wild on Friday. I’m not crying, you’re crying!

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.