Analysis: Will Iran’s establishment collapse after the killing of Khamenei? | Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps

The assassination of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei in joint US-Israeli air attacks has caused one of the most significant blows to the country’s leadership since the 1979 Islamic revolution, triggering protests by his supporters.

Khamenei assumed Iran’s supreme leadership in 1989 after the death of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who had led the Islamic revolution against the pro-United States Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

On Sunday, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian said seeking revenge for the killing of Khamenei and other senior Iranian officials is the country’s “duty and legitimate right”.

President Donald Trump has framed the operation as a “liberation” moment, predicting that the removal of the “head” will lead to the swift collapse of the body. However, in Iran, the reality suggests a far more complex situation.

Interviews with insiders, military experts and political sociologists suggest that the decapitation of Iran’s top leadership may not go the way the West envisions. Instead, it risks birthing a “garrison state” – a paranoid, militarised system fighting for its existence with no political red lines left to cross.

The limits of ‘decapitation’

The central premise of the US operation is that Iran is too brittle to survive the death of its supreme leader. In a phone interview with CBS News, Trump claimed he “knows exactly” who is calling the shots in Tehran, adding that “there are some good candidates” to replace the supreme leader. He did not elaborate on his claims.

However, military analysts warn against the assumption that air strikes alone can trigger “regime change”. Michael Mulroy, a former US deputy assistant secretary of defence, told Al Jazeera Arabic that without “boots on the ground” or a fully armed organic uprising, the state’s deep security apparatus can survive simply by maintaining cohesion.

“You cannot facilitate regime change through air strikes alone,” Mulroy said. “If anyone is left alive to speak, the regime is still there.”

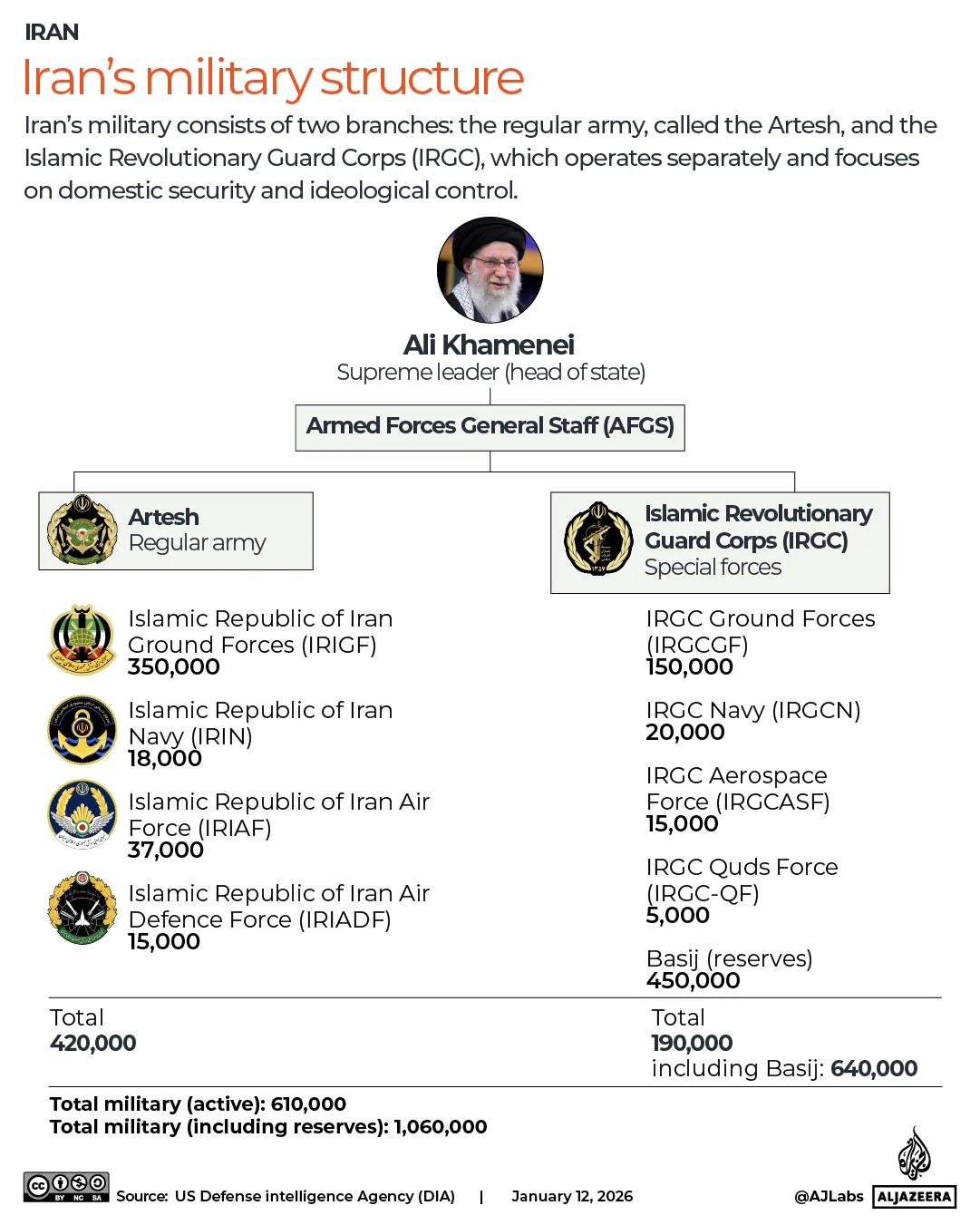

This resilience is rooted in Iran’s dual military structure. The government is protected not just by a regular army (Artesh), but also by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) – a powerful parallel military force constitutionally tasked with protecting the velayat-e faqih system – the principle of the guardianship of the Islamic jurist.

Supporting them is the Basij, a vast paramilitary volunteer militia embedded in every neighbourhood, specifically trained to crush internal dissent and mobilise ideological loyalists.

That cohesion is already being tested.

Hossein Royvaran, a political analyst based in Tehran, confirmed that the strikes wiped out the country’s top security tier, including Khamenei’s adviser and secretary of the newly-formed Supreme Defence Council, Ali Shamkhani.

The secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Ali Larijani, said the leadership transition will begin on Sunday.

“An interim leadership council will soon be formed. The president, the head of the judiciary and a jurist from the Guardian Council will assume responsibility until the election of the next leader,” said Larijani.

“This council will be established as soon as possible. We are working to form it as early as today,” he said in an interview broadcast by state TV.

The rapid formation of an interim leadership council – comprising the president, judiciary chief, and a Guardian Council religious leader – indicates that the system’s “survival protocols” have been activated.

According to Royvaran, the system is designed to be “institutional, not personal”, capable of functioning on “autopilot” even when the political leadership is severed.

But a Tehran-based analyst said direction of Iran is still unclear as officials try to ‘project stability’.

“Officials here are trying to project stability, emphasising that the situation is under control and that state institutions are functioning effectively,” Abas Aslani, senior research fellow at the Center for Middle East Strategic Studies, said.

“Today, [the US-Israeli] air strikes targeted security and military infrastructure in the capital [Tehran] and other cities. There are expectations that such strikes could continue – and possibly intensify – in the coming hours or days,” he told Al Jazeera.

“That prospect of escalation is not something many ordinary Iranians welcome. At the same time, Iranian officials are issuing strong warnings, suggesting they could respond with capabilities that have not previously been used against Israel or the United States.”

From theocracy to nationalist survival

Perhaps the most significant shift in the immediate aftermath is Iran’s pivot from religious legitimacy to survivalist nationalism.

Aware that the death of the supreme leader might sever the spiritual bond with parts of the population, surviving officials are reframing the war not as a defence of the clergy, but as a defence of Iran’s territorial integrity.

Larijani, a conservative heavyweight and key figure in the transition, issued a stark warning that Israel’s ultimate goal is the “partition” of Iran. By raising the spectre of Iran being broken into ethnic statelets, the leadership aims to rally secular Iranians and the opposition against a common external enemy.

This strategy complicates the US hope for a popular uprising.

Saleh al-Mutairi, a political sociologist, notes that the government’s declaration of 40 days of mourning creates a “funeral trap” for the opposition. The streets will likely be filled with millions of mourners, creating a human shield for the government and making it logistically and morally difficult for antigovernment protests to gain momentum in the short term.

The end of ‘strategic patience’

If Iran survives the initial shock, the nation that emerges will likely be fundamentally different: less calculated and probably more violent.

For years, Khamenei championed a doctrine of “strategic patience”, often absorbing blows to avoid all-out war.

Hassan Ahmadian, a professor at the University of Tehran, says the era died with the supreme leader.

“Iran learned a hard lesson from the June 2025 war: Restraint is interpreted as weakness,” Ahmadian told Al Jazeera Arabic. The new calculus in Tehran is likely to be a “scorched earth” policy.

“The decision has been made. If attacked, Iran will burn everything,” Ahmadian added, suggesting that the response will be broader and more painful than anything seen in previous escalations.”

This risks a scenario where field commanders, freed from the political caution of the clerical leadership, lash out with greater ferocity. The assassination has humiliated the security establishment, exposing what Liqaa Maki, a senior researcher at Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, calls a catastrophic intelligence failure.

“The believer is not bitten from the same hole twice, yet Iran has been bitten twice,” Maki said, referring to the pattern of US strikes. This “total exposure” is likely to drive the surviving leadership underground, turning Iran into a hyper-security state that views any internal dissent as foreign collaboration, he said.

While the “head” of Iran has been removed, the “body” – armed with one of the largest missile arsenals in the Middle East – remains, Maki said.