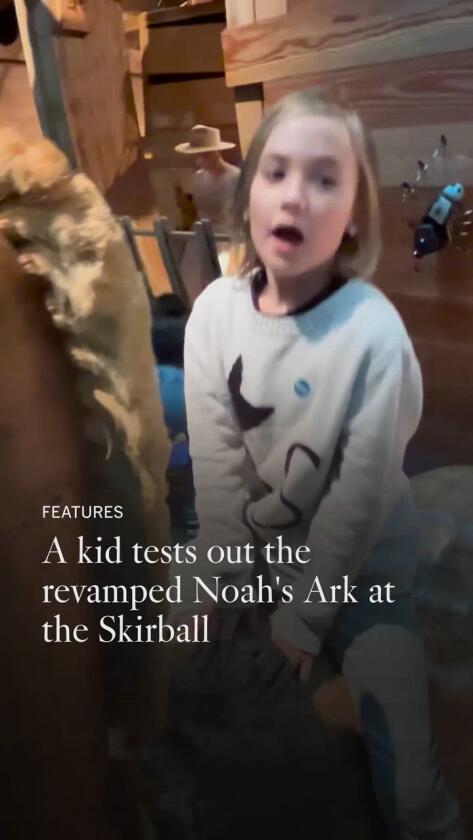

Skirball Cultural Center’s Noah’s Ark exhibit reopens after major renovation

Noah’s Ark, an interactive exhibit for kids at the Skirball Cultural Center, might be the only place in Los Angeles where a parent can ask their child if they want to scoop up some animal poop and receive an enthusiastic, “Yes, please!” That’s not to make light of the interactive experience — which is among the most fun and inspiring activities for children at a local cultural institution — just to note that it’s a fun perk.

The beloved 18-year-old exhibit quietly reopened in mid-December after being closed for more than three months to undergo a renovation that includes enhanced gallery spaces, immersive theatrical lighting and new interactive set pieces like a giant olive tree that kids can curl up inside, as well as slides that serve as exits from the ark and a watering hole for puppet animals that have just reached dry land.

-

Share via

The linchpin of the renovation is a reimagined Bloom Garden planted with native, edible and medicinal plants, and fruit trees including mulberry and pineapple guava — all there to explore at the end of a journey on the ark.

“The goal is not to change the story, but to bring forward a chapter that’s always been there — that moment after the storm, when the work begins,” said Rachel Stark, vice president of education and family programs at the Skirball, adding that the new garden creates “this immersive space where you can imagine the storm waters have receded, the rowboat has washed up onto shore. Things are growing, and you are responsible to help add to that.”

The Bloom Garden, which replaced a simpler ornamental garden, was designed by biodynamic farmer and educator Daron Joffe — known as Farmer D — with the goal of creating a multigenerational space for relaxation and inspiration. It was built around artist Ned Kahn’s existing 100-foot-long Rainbow Arbor sculpture with mist sprayers that create rainbows in sunlight as guests walk through. A trickling stream runs through a valley in the garden, and kids are encouraged to play in and around it. There are hammocks, a sand table and raised garden beds with fresh herbs that families can pick, smell and taste.

Stuffed animals that kids can carry through the exhibit line shelves inside the renovated Noah’s Ark exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center.

(Dania Maxwell / For The Times)

“It’s an inviting space for kids to scramble down into and engage in nature play. It gets them more out of their heads and into the environment,” Joffe said. “I saw kids barefoot out there, which is so cool.”

Parents and children enjoy the Skirball Cultural Center’s new Bloom Garden, which opened alongside the revamped Noah’s Ark exhibit. The garden features raised beds filled with herbs that kids are invited to smell, pick and taste.

(Dania Maxwell / For The Times)

The garden, says Joffe, is a haven for biodiversity, filled with plants that support the full life cycles of butterflies and bees. Shemesh Farms, which employs adults with diverse abilities, will cultivate the garden on an ongoing basis. In addition, the Skirball is looking to hire someone through a Getty Global Art and Sustainability Fellowship. That person will help grow and enhance the garden moving forward.

The Bloom Garden is special in another way: It features the seven ancient plant species that are integral to Jewish teachings, and symbols of the Promised Land — wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives and dates.

The Skirball, founded in 1996, is a Jewish cultural, arts and education center, but it has always been an inclusive space that welcomes people of all faiths, communities and walks of life. The Noah’s Ark exhibit is based on the story of the biblical flood that caused Noah — at God’s direction — to build a ship for his family and two of each animal on Earth. The boat weathered a punishing storm for 40 days and 40 nights, and when the floodwaters receded, those aboard began a new life.

The exhibit also draws inspiration from hundreds of other flood stories from around the world. Taken together, these stories speak to the resilience of nature and the ability of human beings to cooperate — even when they are very different — in order to make meaningful and lasting change, as well as to be responsible and caring stewards of the earth’s bounty.

Susy Doody and her daughter Joy, 21 months, feed parrot puppets inside the Noah’s Ark exhibit.

(Dania Maxwell / For The Times)

Noah’s Ark is organized into three chapters staged in different areas. The first is an entry room where a storm is brewing and animals are loaded into the ark. The second is the interior of the ark, including a “move-in day” room where kids can rummage through food crates and pick up animal puppets to care for, as well as another room with places where they can feed, bathe, put to sleep and clean up after animals (that’s the fake poop!).

There are also climbing nets that kids can use to ascend to the rafters to take care of the animals up top. A system of pulleys allows children on the ground to hoist food to kids above. The third room is the dry land that kids step onto when they disembark from the ark. It features a rainbow, a massive olive tree with a cozy interior nook and a watering hole for the animals.

I recently took my 9-year-old through the exhibit and she had a blast busily engaging with almost every element of the space. She was particularly taken with a blue tarantula puppet and was encouraged by staff to share her journey through the space with her puppet friend. The only sorrow came when it was time to part ways with the hairy creature she had nurtured during the experience.

Allister Celong, 5, climbs through a rope tunnel in the rafters.

(Dania Maxwell / For The Times)

Over the past 18 years Noah’s Ark has hosted more than a million visitors, with about 50,000 people journeying through the space each year. Joffe noted that the exhibit, with its focus on kindness, empathy and the value of shared labor in pursuit of a healthy, sustainable planet, is more timely than ever in this tumultuous, fractured era.

It has been a place of comfort over the years.

“It is a beloved place — one that many visitors grew up coming to,” said Stark. “And then bring their kids back and their grandkids.”