Does Trump’s favorite punching bag, Tren de Aragua, pose a threat to the U.S.?

MEXICO CITY — To help justify a sweeping deportation campaign, an extraordinary U.S. military buildup in the Caribbean and unprecedented strikes on boats allegedly trafficking drugs, President Trump has repeated a mantra: Tren de Aragua.

He insists that the street gang, which was founded about a decade ago in Venezuela, is attempting an “invasion” of the United States and threatens “the stability of the international order in the Western Hemisphere.” Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly on Tuesday, Trump described the group as “an enemy of all humanity” and an arm of Venezuela’s authoritarian government.

According to experts who study the gang and Trump’s own intelligence officials, none of that is true.

While Tren de Aragua has been linked to cases of human trafficking, extortion and kidnapping and has expanded its footprint as Venezuela’s diaspora has spread throughout the Americas, there is little evidence that it poses a threat to the U.S.

“Tren de Aragua does not have the capacity to invade any country, especially the most powerful nation on Earth,” said Ronna Rísquez, a Venezuelan journalist who wrote a book about the gang. The group’s prowess, she said, had been vastly exaggerated by the Trump administration in order to rationalize the deportation of migrants, the militarization of U.S. foreign policy in Latin America, and perhaps even an effort to drive Venezuela’s president from power.

“It is being instrumentalized to justify political actions,” she said of the gang. “In no way does it endanger the national security of the United States.”

Before last year, few Americans had heard of Tren de Aragua.

The group formed inside a prison in Venezuela’s Aragua state then spread as nearly 8 million Venezuelans fled poverty and political repression under the regime of Nicolás Maduro. Gang members were accused of sex trafficking, drug sales, homicides and other crimes in countries including Chile, Brazil and Colombia.

As large numbers of Venezuelan migrants began entering the United States after requesting political asylum at the southern border, authorities in a handful of states tied crimes to members of the gang.

It was Trump who put the group on the map.

While campaigning for reelection last year, he appeared at an event in Aurora, Colo., where law enforcement blamed members of Tren de Aragua for several crimes, including murder. Trump stood next to large posters featuring mugshots of Venezuelan immigrants.

“Occupied America. TDA Gang Members,” they read. Banners said: “Deport Illegals Now.”

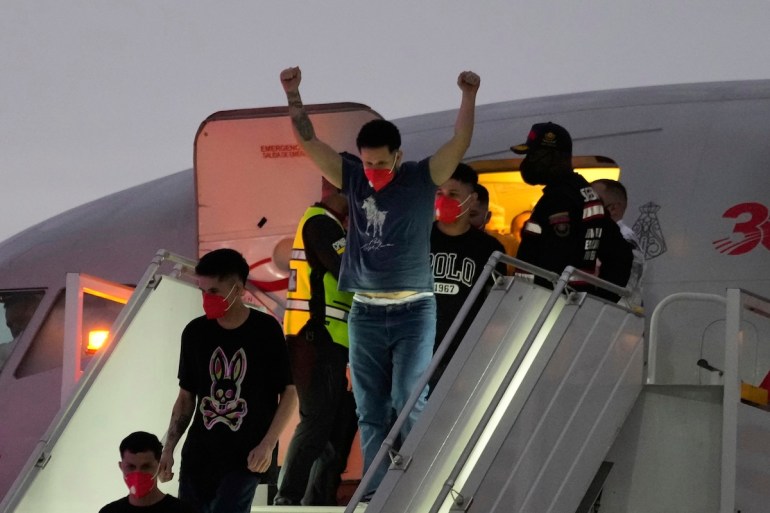

Shortly after he took office, Trump declared an “invasion” by Tren de Aragua and invoked the Alien Enemies Act, a rarely used 18th century law that allows the president to deport immigrants during wartime. His administration flew 200 Venezuelans to El Salvador, where they were housed in a notorious prison, even though few of the men had documented links to Tren de Aragua and most had no criminal records in the United States.

In recent months, Trump has again evoked the threat of Tren de Aragua to explain the deployment of thousands of U.S. troops and a small armada of ships and warplanes to the Caribbean.

In July, his administration declared that Tren de Aragua was a terrorist group led by Maduro. That same month, he ordered the Pentagon to use military force against Latin American cartels that his government has labeled terrorists.

Three times in recent weeks, U.S. troops have struck boats off the coast of Venezuela that it said carried Tren de Aragua members who were trafficking drugs.

The administration offered no proof of those claims. Fourteen people have been killed.

Trump has warned that more strikes are to come. “To every terrorist thug smuggling poisonous drugs into the United States of America, please be warned that we will blow you out of existence,” he said in his address to the United Nations.

While he insists the strikes are aimed at disrupting the drug trade — claiming without evidence that each boat was carrying enough drugs to kill 25,000 Americans — analysts say there is little evidence that Tren de Aragua is engaged in high-level drug trafficking, and no evidence that it is involved in the movement of fentanyl, which is produced in Mexico by chemicals imported from China. The DEA estimates that just 8% of cocaine that is trafficked into the U.S. passes through Venezuelan territory.

That has fueled speculation about whether the real goal may be regime change.

“Everybody is wondering about Trump’s end game,” said Irene Mia, a senior fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think tank focused on global security.

She said that while there are officials within the White House who appear eager to work with Venezuela, others, including Secretary of State Marco Rubio, are open about their desire to topple Maduro and other leftist strongmen in the region.

“We’re not going to have a cartel operating or masquerading as a government operating in our own hemisphere,” Rubio told Fox News this month.

Top U.S. intelligence officials have said they don’t believe Maduro has links to Tren de Aragua.

A declassified memo produced by the Office of Director of National Intelligence found no evidence of widespread cooperation between his regime and the gang. It also said Tren de Aragua does not pose a threat to the U.S.: “The small size of TDA’s cells, its focus on low-skill criminal activities and its decentralized structure make it highly unlikely that TDA coordinates large volumes of human trafficking or migrant smuggling.”

Michael Paarlberg, a political scientist who studies Latin America at Virginia Commonwealth University, said he believes Trump is using the gang to achieve political goals — and distract from domestic controversies such as his decision to close the investigation into convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein.

Tren de Aragua, he said, is much less powerful than other gangs in Latin America. “But it has been a convenient boogeyman for the Trump administration.”