These days, almost every cultural or news event seems fleeting. But there’s one thing that feels nearly as momentous as it did 20 years ago: the Super Bowl.

From a personal point of view, I can say that despite basically divesting myself from football (I haven’t watched a non-Super Bowl NFL game in well over a decade, and haven’t played fantasy football for just as long), I still participate in what has become, essentially, a national holiday. Maybe that’s just it: In the ideologically fractured world of 2026, there’s something to be said for having at least one relatively universal experience.

You’re reading Boiling Point

The L.A. Times climate team gets you up to speed on climate change, energy and the environment. Sign up to get it in your inbox every week.

By continuing, you agree to our Terms of Service and our Privacy Policy.

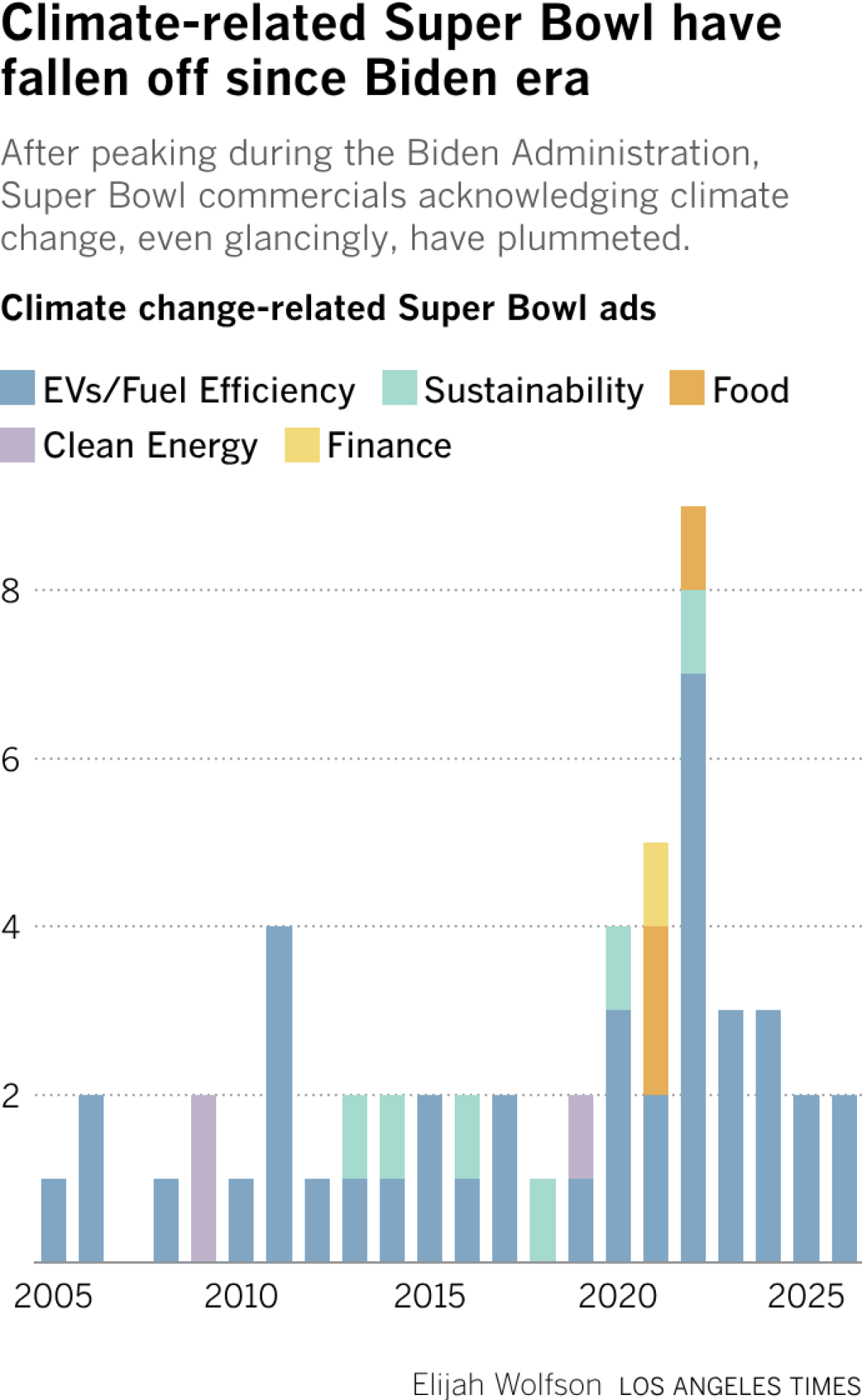

In any case, such a uniquely shared media event inevitably reflects the cultural milieu of the moment. That’s why, for a while now, I’ve been tracking how many of the commercials that air during each year’s Super Bowl have some relation to the environmental issues that I’ve been covering for most of my career as a journalist. I started this project when I was an editor at Time magazine, and thought it merited revisiting this year. Here’s what I found.

During Super Bowl LX on Sunday, there were just two commercials that focused in a meaningful way on products that would advance a transition to a fossil-fuel-free economy. One was for the 2026 Jeep Cherokee Hybrid. The other was for a Chinese supercar made by a vacuum-cleaner company.

It wasn’t long ago that domestic manufacturers were marketing a future based on electric vehicles of all shapes and sizes. During the 2022 Super Bowl, the second year of Joe Biden’s presidency, seven different ads focused specifically on existing and new EV models. Those were in some ways the halcyon days of American EV manufacturing, following the passage of the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, which, in part, offered a $7,500 tax credit to anyone who bought a new electric car.

The second Trump administration quickly put an end to that; the credit was nixed as of Sept. 30 last year. That was just one of many moves Trump has made since retaking office to anesthetize the United States’ nascent green economy. Over the last year, the Trump administration has tried to shut down offshore wind energy projects while demanding the growth of the coal industry; reversed key policies that previously established legal precedent for the public health impact of greenhouse gases; and generally tried to undermine efforts by many states, California especially, to establish and regulate policies meant to make their infrastructure less dependent on fossil fuels.

So it’s no surprise that in 2026, the second year of Trump’s second presidency, there was just one Super Bowl ad for a domestically produced green product — and it wasn’t even entirely green. Indeed, it reflects a recent trend across the U.S.: Since the federal clean-vehicle tax credits expired in September, sales of purely electric vehicles have plummeted, while those of hybrids have continued to grow, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Tellingly, four different companies — Cadillac, Toyota, Volkswagen and Chevrolet — had ads that showed an EV but didn’t mention it. It’s become more something to hide than to promote.

Then there’s the one other green-energy ad this year, which, honestly, you could quibble with categorizing it as “green.” It’s a reportedly $10-million spot for an electric sports car, theoretically to be made by the Chinese company Dreame, which to date has primarily produced robotic vacuum cleaners. I say theoretical because it seems somewhat unlikely that an outfit that made its nut building knockoff Roombas will be selling an electric super car anytime soon. (As of writing, Dreame has not responded to emailed questions.)

Nevertheless, it is indicative of another trend: Tesla is down; BYD is up. U.S. car companies like Ford can’t seem to figure out how to transition to a gas-less (or, at least, less gas-forward) future, while many Chinese firms, some without any automotive heritage, such as the consumer-tech company Xiomai, are already driving laps around U.S. and European competitors in what is clearly the race for the future of global car-manufacturing dominance.

In 2025, more than half the cars made in China were EVs. And China is working to power those electric cars with renewable energy, while the U.S. is largely swimming against the tide. In 2025, China installed an estimated 315 gigawatts of solar and 119 gigawatts of wind capacity; the U.S. added an estimated 60 gigawatts of solar and 7 gigawatts of wind capacity in the same time.

Green tech doesn’t seem to have much cultural currency right now in the U.S., at least based on the Super Bowl ad lineup. What does, though, is artificial intelligence. There were at least eight different Super Bowl commercials for AI products, and many more that obviously used AI in their production.

Even setting aside the many intellectual-property and ethical issues they raise, there’s the reality that these AI tools rely on data centers that, in turn, require a huge amount of energy to operate — energy that should, ideally, be coming more and more from renewable sources.

Maybe it’s not all that sexy to advertise solar panels or wind turbines — but it also wasn’t that long ago that a pitch about talking to your hand-held computer to help with your scheduling would have seemed pretty lame.

More in climate and culture

One more thing about the Super Bowl: In this pretty cool video, Pearl Marvell, an editor at Yale Climate Connections, broke down the climate change references in Bad Bunny’s halftime performance.

In other sports+climate news, my colleague Kevin Baxter, reporting from Italy, wrote about the impact climate change is having on this — and future — Winter Olympics. The bottom line: Athletes are going to have to expect less fresh powder, and deal with more dangerous, icy conditions.

Last sports-related story of the week: My former colleague Sammy Roth recently wrote a nice profile of Jacquie Pierri, who plays for the Italian women’s hockey team and moonlights as a sustainable-energy engineer and climate activist. Italy plays the U.S. in the quarterfinals on Friday.

On a different note, on the podcast Zero, Akshat Rathi this week interviewed composer Julia Wolfe about how she uses classical music to work through, and communicate, her feelings about the climate crisis.

A couple of last things in climate news this week

California created a program meant to encourage the development of electric semi-trucks. But, as my colleague Tony Briscoe reported a few days ago, Tesla took advantage of it, claiming most of the money while failing to deliver and essentially bullying smaller manufacturers out of the space.

The Trump administration has indicated that it plans this week to rescind the so-called endangerment finding, a policy establishing the fact that greenhouse gases endanger public health, and that essentially acts as the legal underpinning for many climate regulations passed in recent years. Stay tuned — our reporters will have more on this as the story develops.

This is the latest edition of Boiling Point, a newsletter about climate change and the environment in the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox. And listen to our Boiling Point podcast here.