MONTEREY COUNTY, Calif. — The summer sun burned through the clouds in the Salinas Valley, where a bounty of berries and leafy green vegetables grows across this rich farmland renowned as the “Salad Bowl of the World.” Jose, a quiet 14-year-old, was squatting and bending over for hours with other workers in a sprawling strawberry field.

The pickers, many of them also minors, snapped berries from plants and placed them in plastic cartons, eight of them in a cardboard box. They moved quickly along the long rows that lined the field.

Jose was exhausted but working as fast as he could; he was being paid $2.40 for each box he filled. As he ran with a full box, he fell on the uneven ground and twisted his ankle. It hurt for days, he later recalled, but he didn’t say anything to his boss for fear of losing his job.

Jose, seen at 13, picks strawberries in the Salinas Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 11 years old and has injured his ankles and knees after falling down at work. He says he has been paid piece-rate wages for less than minimum wage and he has worked in fields on hot summer days where employers failed to provide shade. He also described working in a field where a strong smell of chemicals gave him a headache.

“You just gotta suck it up, and you gotta work through it,” he said on a recent Sunday, his only day off that week. He has labored in the fields every summer and on weekends during the school year since he was 11 years old to help his mother, who also picks berries. His siblings, uncles and cousins — four of them minors — work in local strawberry fields.

Jose said that some days he didn’t fill many boxes and earned less than minimum wage for the hours he worked, which would be a violation of state child labor laws. He described toiling under the hot sun in fields where employers failed to provide shade for workers, as required by state law. He and his sister said they harvested strawberries in a field where a tractor had sprayed a liquid with a strong chemical odor.

“It really smelled bad,” he said. “It gave me headaches.”

Jose and thousands of other children and teenagers are part of a faceless legion of underage workers in California who put fresh fruit and vegetables on America’s tables. In California, laborers as young as 12 can legally work in agriculture. But many of them toil in punishing and dangerous conditions, and the state is failing to ensure their health and safety, an investigation by Capital & Main has found.

Enforcement of child labor laws has been inconsistent, the number of workplace safety inspections and citations issued to employers have dropped and repeat offenders were not fined for hundreds of violations of pesticide safety laws, according to a review of tens of thousands of state and county records detailing inspections, violations and money collected for civil penalties.

Angelica, seen at 15, picks tomatillos in the Santa Maria Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 11 years old. She says she is paid $3 for each five-gallon bucket of tomatillos she fills. On a typical workday of about five or six hours, she says she can fill three buckets — earning just $9 for her labor. She described toiling in fields where employers failed to provide shade and drinking water.

Piece-rate work

Farmworkers have to work faster to earn as much as they can. Rates vary, depending on various factors, but here are some of the payments per unit.

An eight-carton box of strawberries

A five-gallon bucket of tomatillos

A 500-pound crate of oranges

Interviews with farmworkers and the United Farm Workers union.

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

Capital & Main spoke with 61 young field workers — from 12 years old to those who had recently turned 18. Many described experiencing headaches, skin rashes or burning eyes while working in fields that smelled of chemicals. Others said they were hired for piece-rate jobs that paid less than minimum wage. Many recalled struggling in the summer sun without shade or extra water breaks. Some talked of using filthy portable toilets with no soap to wash their hands.

Several came alone to the United States from Mexico. But most, like Jose, were born in the U.S. and work alongside their immigrant parents — many of whom are Mixtecos, Indigenous people who emigrated primarily from the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Michoacán and Guerrero.

These young laborers and their families are caught in the crosshairs of the Trump administration’s recent immigration raids on worksites. Many of the parents are undocumented and work in agriculture. This creates additional stress, young workers say, because they worry that their families could be broken apart if immigration authorities descend on the fields.

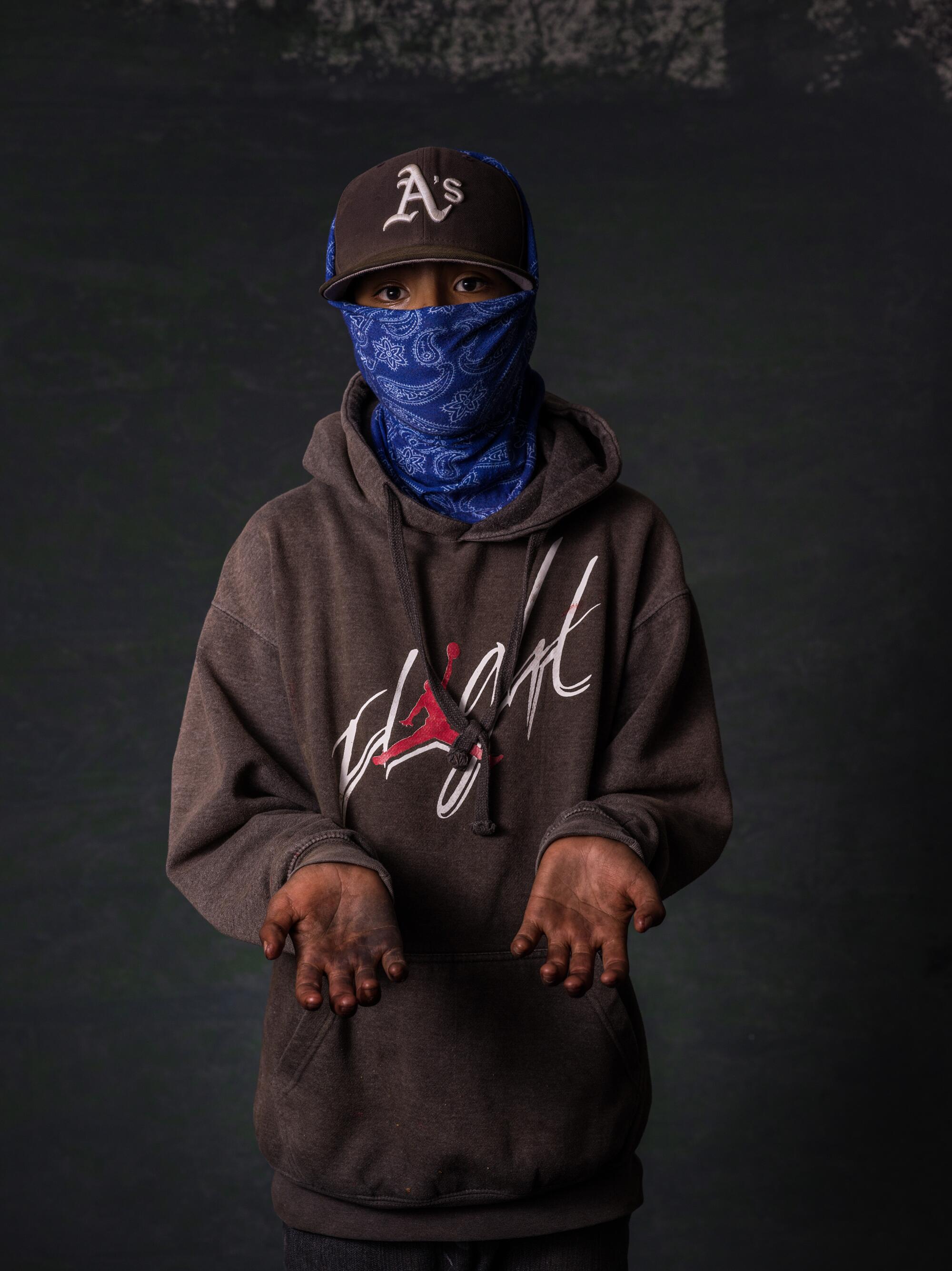

Brian, seen at 16, harvests citrus fruit in the San Joaquin Valley. He started working in the orchards when he was 12 years old to help his father buy food and pay the bills. He works with several family members, often in piece-rate jobs that pay less than minimum wage, he and his father say. His family says they fill large crates with 500 pounds of lemons, oranges and grapefruit, often in triple-digit heat without any company-paid breaks.

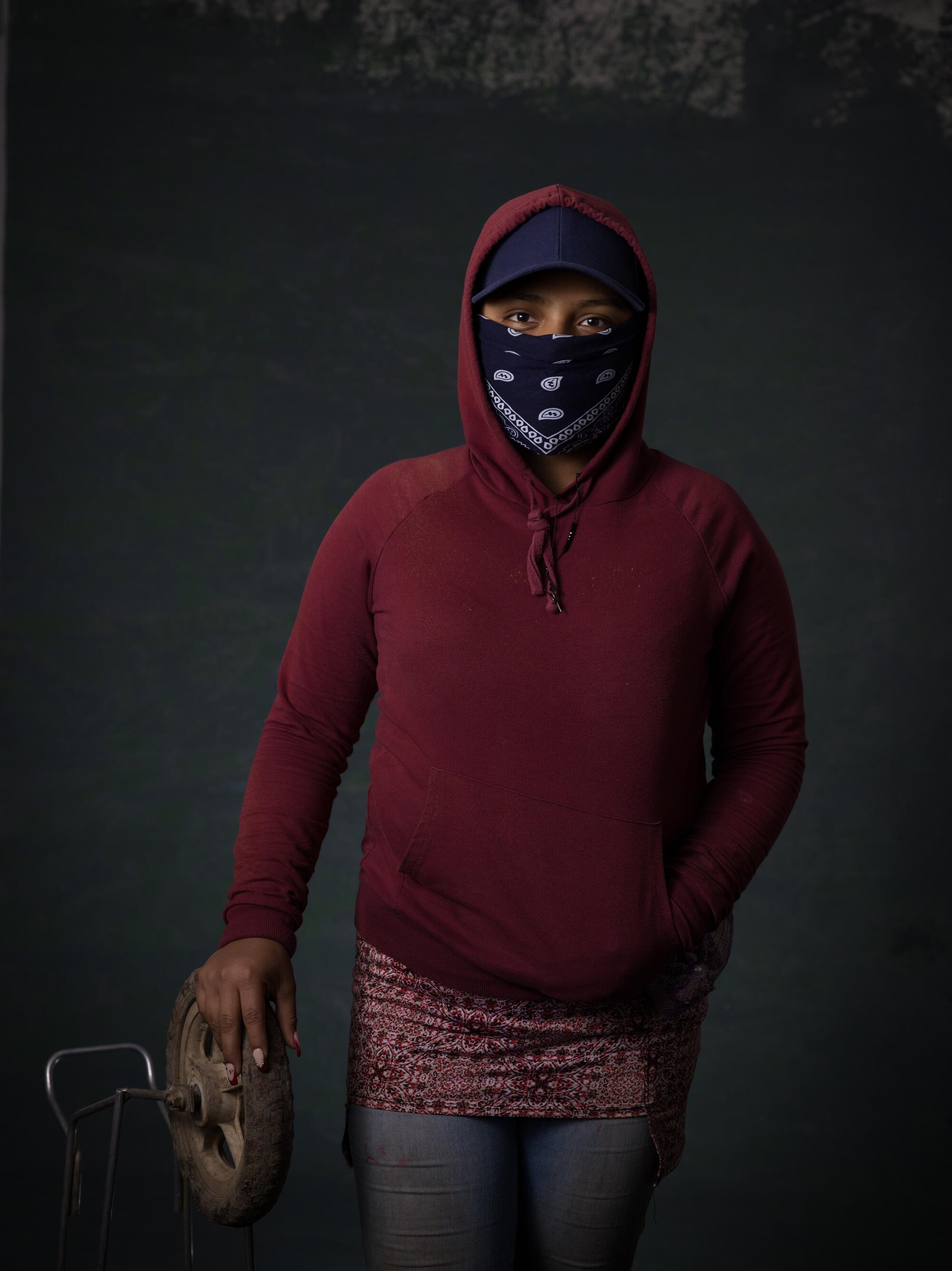

Raquel, seen at 18, picks strawberries in the Salinas Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 11 years old to help her immigrant parents. She graduated from high school with a 4.0 grade point average and attends college. She dreams of becoming a nurse and using her Spanish and Mixteco language skills to help her community. She described entering a field where a tractor had sprayed chemicals that made her feel dizzy. She also says she has worked piece-rate jobs that paid less than minimum wage and labored in fields where employers failed to provide shade on hot days.

The climate of fear has made families more reluctant than ever to complain about unsafe working conditions, concerned that employers will retaliate. Even so, young people continue to work to help their parents pay bills and put food on the table.

In most cases, California requires minors to be 14 years old to work. But under state law, children as young as 12 can labor up to 40 hours a week in the agricultural industry when school is not in session.

Pesticide use is widespread across California’s farmlands and signs such as this one in the Salinas Valley are required to be posted in fields that have been recently sprayed.

Raquel, seen at 18, picks strawberries in the Salinas Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 11 years old to help her immigrant parents. She graduated from high school with a 4.0 grade point average and attends college. She dreams of becoming a nurse and using her Spanish and Mixteco language skills to help her community. She described entering a field where a tractor had sprayed chemicals that made her feel dizzy. She also says she has worked piece-rate jobs that paid less than minimum wage and labored in fields where employers failed to provide shade on hot days.

California leaders take pride in the state’s stringent workplace safety laws that generally exceed federal regulations and include labor codes to protect underage workers, landmark outdoor heat safety standards and pesticide safety regulations.

Yet vast areas of California’s agricultural heartlands have gone years without worksite inspections by the front-line state agency charged with protecting underage workers, according to the records. Over an eight-year period, state officials issued just 27 citations for child labor violations, even though thousands of agricultural businesses operate in California. More than 90% of the fines were never collected.

At the same time, state officials failed to investigate a majority of the 2,600 complaints filed against agricultural employers for not providing heat-illness training, shade or cool water for workers on hot days, the records show, and the number of citations issued for worksite safety violations dropped by 74% in the last decade. In more than 600 agricultural safety investigations, officials never visited worksites and instead performed “letter investigations,” or querying employers by mail.

Between 2018 and early 2024, county regulators cited more than 240 businesses for at least 1,268 violations of state pesticide safety laws in three or more counties, an analysis of more than 40,000 state enforcement records shows. But for nearly half of those violations — many of them pertaining to worker safety — the companies paid no fines and received only warnings or notices to correct the problems.

And in California’s top-producing agricultural regions in 2023, county regulators performed inspections in less than 1% of the more than 687,000 instances in which fields and orchards were sprayed with pesticides, some known to cause cancer, according to the records.

“These enforcement agencies just have no teeth at all,” said Jack Kearns, a policy advocate with the UCLA Labor Center, who has researched child labor abuse. “They are just understaffed and they don’t have the capacity.”

Bryan Little of the California Farm Bureau, which represents thousands of agricultural businesses, said he has visited many farms and added, “I don’t ever recall seeing anybody working in a farm field who appeared to be under the age of 18.”

Lorena, seen at 16, picks strawberries in the Santa Maria Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 11 years old and described working on hot days and drinking water provided by her bosses. It tasted foul, she says, because the jugs had not been washed. She also says that she was exposed to pesticides, including one time from spray from a nearby tractor. The chemicals made her eyes burn and she broke out in rashes, she says.

According to Little, the bureau’s senior director of policy advocacy, minors don’t labor in the fields because they attend school and also have to apply for work permits from their school districts. He said he has “rarely seen anything concrete” to support allegations of worker exploitation in California’s agricultural industry, claiming that many reports originate from advocacy groups that fail to provide evidence to back up their claims.

Even so, most of the young workers interviewed said they typically work six days a week in the summer and, when school is in session, on the weekends. Some businesses didn’t allow underage workers, they said, while others look the other way and don’t inquire about ages. None of the youths said they were aware they needed work permits.

One 15-year-old said he began working when he was 6; another said she was 9. Most said they were between 11 and 13 years old when they were initiated into the harsh work culture of the fields. They include a student who graduated from high school with a 4.0 grade point average and several others who now attend California universities.

Derick, seen at 14, picks strawberries in the Salinas Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 13 years old to help his parents, Indigenous Mixtecos who came to the U.S. from the Mexican state of Oaxaca. He says the work is hard on his back, shoulders and legs. His large family, including his uncles and cousins, works in the fields.

In the San Joaquin Valley, a 12 year-old boy scales a ladder to harvest lemons. In Hollister, underage siblings use sharp knives to cut and clean heirloom apricots that dry in the hot sun. And in the Santa Maria Valley, a diminutive 15-year-old girl struggles to load a large bucket with 20 pounds of tomatillos, earning $3 for each one she fills.

These young workers help power California’s annual $61 billion agricultural industry, the most productive in the nation and one of the biggest in the world.

Miriam Andres is a social worker who connects families with resources in the farming town of Parlier in the central San Joaquin Valley, where she estimated that several hundred underage young people work in fields and orchards with their parents.

“There are laws that say you have to be a certain age to work. There’s things like work permits. But really, behind all this is a family not making ends meet,” said the 35-year-old Andres, who helped her father harvest raisins when she was 13.

“What really needs to change is how much ag workers get paid,” she said, “so that minors don’t have to help out their parents.”

Researchers who study child labor say there are no solid numbers on how many minors work in California agriculture, in part because of the transient nature of the work and limited tracking by government agencies. But based on interviews with experts and labor advocates who assist field workers, as well as findings from the National Agricultural Workers Survey, a fair estimate would be that 5,000 to 10,000 underage youths labor in the state’s agricultural industry.

Rosalia, seen at 18, is a strawberry picker in the Santa Maria Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 12 years old and picked blueberries. She described working in strawberry fields that had a strong chemical, like “Clorox or oil.” She also says she has fallen in the fields and bruised her knees and suffered cuts on her fingers from picking berries.

From 2017 through 2024, California issued only 27 citations for child labor violations to agriculture employers . . .

. . . the state has 17,000 agriculture employers.

UC Davis report and Department of Industrial Relations

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

The primary agency in California for regulating child labor and workplace safety laws is the state Department of Industrial Relations.

For 11 months, the department failed to respond to repeated California Public Records Act requests for detailed enforcement records. Officials provided all the requested data only after the Press Freedom Project at the UC Irvine School of Law wrote a letter specifying violations of state public records law and threatening to file a lawsuit.

A review of records from 2017 through 2024 for the department’s Bureau of Field Enforcement, which regulates child labor laws, shows that officials issued just 27 citations in the period for child labor violations to agricultural employers across California. There are 17,000 agricultural employers in the state, according to a recent UC Davis report.

The fines totaled $36,000, according to the records, but the state collected only $2,814.

From 2017 through 2024, agricultural employers in California were fined $36,000 for child labor violations, but . . .

= $1,000

. . . only $2,814 in fines were collected.

Department of Industrial Relations

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

“That’s a minuscule percentage. It’s obvious they’re not pursuing the issue of child labor abuse,” said Darlene Tenes, executive director of Farmworker Caravan, which connects underage field workers in the Central Coast with mentors and social service agencies.

The department said in a statement that the Labor Commissioner’s Office, which oversees the bureau, does all it can to collect penalties and that “workers are always prioritized first” for receiving any money recovered from violators.

Erika Monterroza, a department spokesperson, said in a statement that the bureau has had “numerous enforcement successes” across all the industries it regulates. She faulted the pandemic for affecting enforcement, reducing staffing and creating “challenges for the unit.”

Rey, seen at 18, picked strawberries in the Pajaro Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 14 years old. He recalled picking berries while a tractor in an adjacent field was spraying. The strong wind blew the spray toward him and other workers. It smelled like chemicals, he says. He recently enlisted in the military.

As of May, the bureau had 53 field investigators responsible for covering the entire state and 14 vacant positions. Investigators, who also enforce wage and hour laws, are responsible for inspecting the operations of more than a half-dozen industries across California that include construction sites, hotels and car washes.

Of the 27 citations issued to agricultural employers from 2017 through 2024, nearly all were for failing to have work permits on file for underage workers.

“The owners clearly turn a blind eye,” said Erica Diaz-Cervantes, 25, a former underage farmworker who is now a senior policy advocate for the Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy.

Employers are required to have permits for minors and know the ages of their workers. Youths under 16 years old, for instance, are limited to eight hours of work a day and 40 hours a week when school is not in session (rules are stricter during the school year). Permits are issued by school districts, which are required by state law to inform students of their work rights.

Three sisters, including Araceli, who plants vegetables in Santa Maria Valley fields, share this bedroom in the family’s apartment.

About 20 of the youths interviewed said that in some instances they labored up to 10 hours a day when they were 12 and 13 years old. Some acknowledged using false identification, but most described experiences similar to that of a 16-year-old from Santa Barbara County, who said her bosses never inquired about her age.

A shy girl who dreams of becoming a nurse, the teenager has spent the last four years working with her mother and other relatives at small ranches, where they pull weeds, plant berries and remove old plastic tarps from fields.

Araceli, seen at 16, has planted lettuce, cauliflower and broccoli in the Santa Maria Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 13 years old to help her immigrant parents pay the bills. She recalled suffering a nosebleed in the heat in a field where there was no shade, as well as working in fields that reeked of chemicals. She says the skin peeled off her fingers and they turned white. She graduated with a 3.9 grade point average and earned a scholarship from a California university.

In 2023, the teenager said, she and other laborers toiled in a field for more than a month without being paid. Some of the adults complained to the boss.

“He kept saying, ‘I’ll pay you next week, I’ll pay you next week,’” she said.

On some days, she said, there were no portable toilets at the field and no water or shade provided for workers.

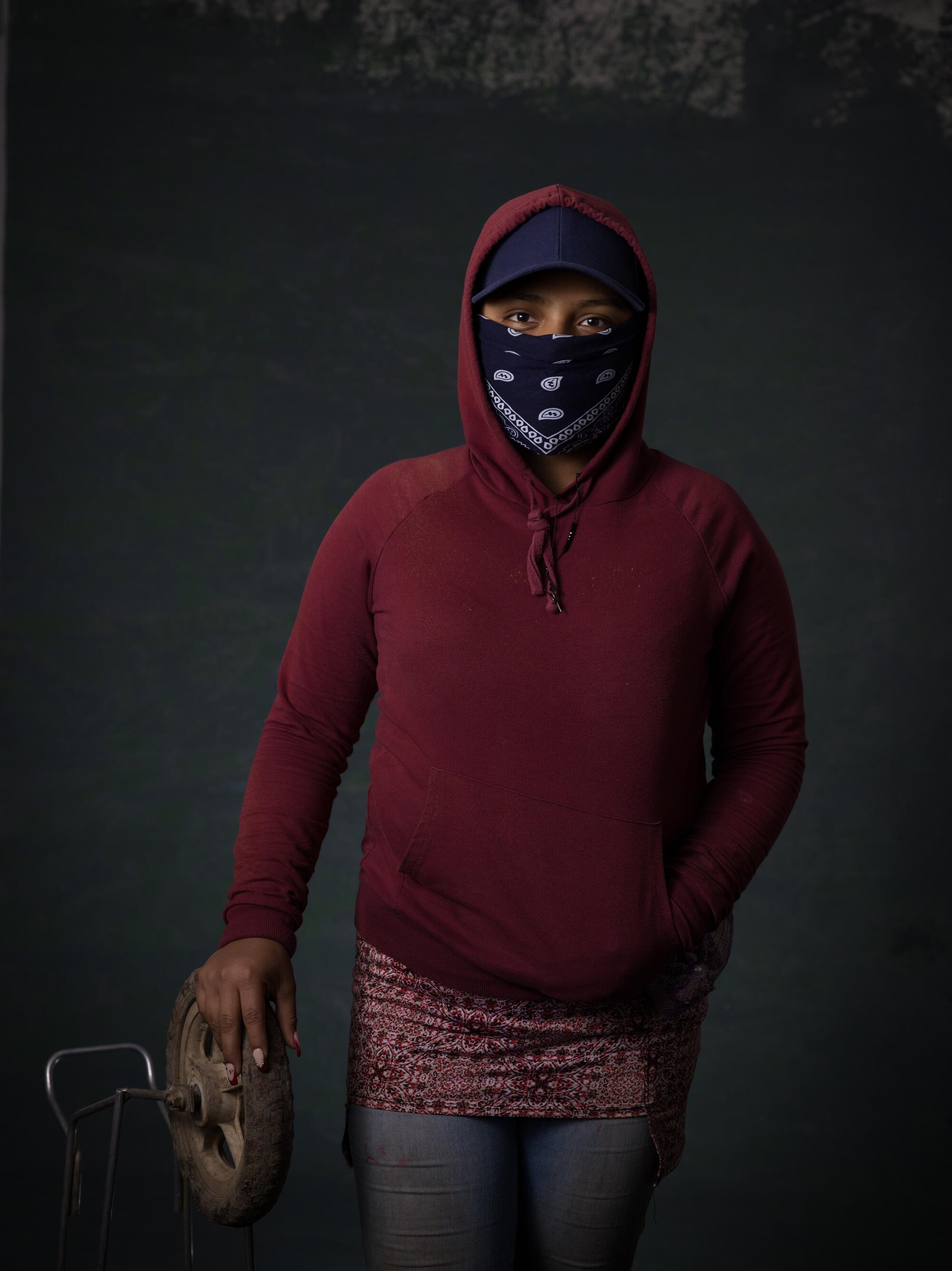

Alexandra, seen at 14, picks strawberries in the Santa Maria Valley. She started working in the fields when she was 12 years old to help her single mother. On workdays, she gets up at 4 a.m. to get to the fields on time. She wears layers of clothes and a bandana around her face to protect herself from chemicals on the plants that she says burned her nostrils as she breathed. On hot days, she says, there were no extra water breaks provided for her and other workers.

They were finally paid in cash after the job was completed; she wasn’t sure if she received all the money she was owed.

The fertile area where the mother and daughter work is one of the largest producers of strawberries in the nation. Yet abuse and exploitation in the fields are commonplace, according to the mother, who said that workers are mistreated because employers know they won’t be caught.

“We tell the supervisors, and they say, ‘If you don’t like it, there are many others who want your job,” the mother said in Spanish, asking not to be named for fear of retaliation by her bosses.

Inspectors from the Santa Barbara office of the Bureau of Field Enforcement are responsible for regulating child labor and wage and hour laws in the 2,700-square-mile county, where more than 600 agricultural businesses operate.

The Santa Barbara office performed an average of just two worksite inspections a year from 2017 to 2024, the records show. There were no inspections in 2017, 2018 and 2020.

The bureau’s Fresno office is responsible for inspecting worksites across more than 5,000 square miles of some of California’s most productive farmlands in the central San Joaquin Valley.

Records show that the Fresno office conducted an average of less than four inspections a year from 2017 through 2024 — in an area where there are more than 3,000 agricultural employers. There were no inspections from 2021 through 2023.

Emma Scott, an associate professor who directs the Food and Agriculture Clinic at the Vermont Law and Graduate School, said the low number of inspections in areas with such large numbers of farmworkers “boggles my mind.”

“That’s pretty shocking, actually,” said Scott, who has studied health and safety protections for agricultural workers.

Damian, seen at 17, picked strawberries in the Salinas Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 13 years old. He said the work is harsh and that his arms, back and legs get sore, especially at the start of the season. He recalled eating lunch along the side of the field while a nearby tractor sprayed liquid that smelled like chemicals. The wind blew the spray on him and his sister as they ate, he says.

Adrian, seen at 18, picks strawberries and blueberries in the Santa Maria Valley. He says he has worked in fields where employers failed to provide shade and water on hot days. He sketches images, some of which highlight farmworkers laboring in abusive conditions. He attends college and is interested in pursuing his artistic talents.

The region covered by the bureau’s Fresno office is home to hundreds of young laborers like 17-year-old Brian. He harvests citrus fruit with his 16-year-old cousin and 13-year-old brother for piece-rate wages that amount to less than minimum wage.

The three teens live with four other family members in a neighborhood filled with faded mobile homes not far from the green orchards of the San Joaquin Valley’s citrus belt. Brian’s home sits on a dirt lot, where several chickens peck at the weeds next to a table under a large tarp that blocks the sun during hot summer months.

The bulk of the nation’s oranges, lemons and mandarins are grown in these orchards, primarily in Fresno, Tulare and Kern counties. The three were the nation’s top agricultural counties in 2024, grossing a total production value of $25 billion.

Adrian, seen at 18, picks strawberries and blueberries in the Santa Maria Valley. He says he has worked in fields where employers failed to provide shade and water on hot days. He sketches images, some of which highlight farmworkers laboring in abusive conditions. He attends college and is interested in pursuing his artistic talents.

On weekends and in the summer when there’s no school, the three teens help Brian’s father pick oranges, lemons and grapefruit. The work is seasonal and depends on which fruit is ready for harvesting, as well as on how many others are looking to be hired. When the family is lucky, they have jobs lined up for several days. When they don’t, they get up before the sun rises, eat breakfast, make egg burritos for lunch and drive to orchards looking for work.

Brian and his cousin scale tall ladders while wearing large canvas bags with up to 40 pounds of fruit — often in triple-digit heat. The 13-year-old brother picks up any fruit that falls to the ground and helps load it into crates.

The work takes a toll on the body. “It hurts a lot,” said Brian, who has toiled in the orchards since he was 13. “Your neck, back, arms are sore.”

At times, the cousin recalled, he felt dizzy and nauseated. “You have to keep going,” he said in Spanish. “Hour by hour.”

He was sideswiped last year by a small tractor, injuring his hip. But he kept quiet, he said, because he didn’t want to call attention to his age.

Brian and his cousin are athletic, with broad shoulders and thick biceps, and they dream of a life beyond the fields. Brian may enlist in the military; his cousin would like to learn a trade, maybe welding or work in construction.

The jobs typically last six hours at small orchards — and there’s no company-paid breaks. If you need to rest, the father said in Spanish, “That’s your problem.”

He said they earn $20 to $25 for each 500-pound crate of oranges they load.

Brian and his cousin can fill three crates each during a typical six-hour job, earning the equivalent of $10 to $12.50 an hour. The rate is even less for picking grapefruit, which pays $8 to $10 per 500-pound crate, according to the father and the two teens.

Angelica Preciado, an attorney with California Rural Legal Assistance, said the production standards for six-hour jobs that pay piece-rate are “ridiculously high.”

Luis, seen at 17, picks strawberries in the Salinas Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 13 years old. He and his mother were fired from his first job, he says, because he was unable to work fast and fill enough boxes with berries. He described working in a strawberry field while a nearby tractor was spraying a grayish fluid that smelled like chemicals. It made his eyes watery, he says.

Pickers have to work harder and faster to make as much as they can in a shorter workday, she said, noting that six-hour jobs also ensure that employers don’t have to pay overtime.

A California law requiring overtime for farmworkers went into effect in 2019, but a recent UC Davis study found that the rules have led to a reduction in work hours and earnings for crop workers.

Employers are required to pay piece-rate laborers at least the equivalent of minimum wage, which is currently $16.50 an hour for most employees, but even if they don’t, workers — especially minors — don’t complain.

“A lot of that has to do with fear,” said Preciado, who has investigated alleged child labor abuses in California’s agricultural industry.

On a hot Sunday afternoon, Brian’s father sat at a table in the family’s mobile home. The place, which rents for $1,200 a month, has three small bedrooms and an open space that serves as the kitchen, dining area and living room. A small air conditioner mounted in a window struggled to keep the room cool.

Since immigration authorities began raiding fields and neighborhoods, he said, the family doesn’t go out as much as before, and they’re always watching over their shoulders when they’re on the streets.

“Many of us live with that fear that ICE or Border Patrol will detain a family member and [we will] lose everything,” Brian said in Spanish.

The father dropped out of school in Mexico when he was 13 years old to work with his parents in the fields. On good weeks when work is plentiful, the father said, the boys can bring in an extra $300 to $500. He said the family visits a food bank once a month for staples such as rice and beans.

He wants his children to do better, but for now, he needs their help to get by.

“I don’t want them to work in the fields like me,” he said. “I want them to have a career.”

Strawberry pickers, like those seen here in the Salinas Valley, squat and bend over for hours on a summer day.

Araceli started working in the lush plains of the Santa Maria Valley when she was 13, alongside her older sister and immigrant parents, Indigenous Mixtecos who came to California as teenagers from a small town in Oaxaca, Mexico.

With fertile soil, abundant sunshine and moist coastal air, the funnel-shaped valley is noted for long growing seasons and a wide array of crops. Much of the valley lies in Santa Barbara County, where agriculture generated a production value of more than $2 billion in 2024.

Now 17 and interested in science, Araceli graduated from high school with a 3.9 grade point average and received a scholarship from a California university. A veteran of the farm fields, she has planted lettuce, broccoli and cauliflower.

She and her mother described planting broccoli on a hot summer afternoon in a field where there was no shade. Araceli was dizzy and nauseated. She felt something dripping from her nose — then saw blood on the long sleeves of her shirt.

She ran to a portable toilet and grabbed a handful of paper towels to stanch the bleeding. She hustled back because, she said, she was afraid of angering her boss.

Federico, seen at 16, picks strawberries in the Pajaro Valley. He started working in the fields when he was 14 years old. He recalled one of his bosses yelling at him when he sat down in the fields to take a break. He was tired and his body ached, he says, but the boss was “mean” and ordered him to get back to work.

“It’s, like, strongly discouraged. … You do not stop,” Araceli said. “You have to keep going. So I really couldn’t do anything about it.”

The work can be dangerous in other ways. This past summer, Araceli was assigned to a transplanting machine, where she and others sat in the rear of the tractor-like vehicle, quickly placing vegetable seedlings into metal cones that sow the small plants into the soil.

She worked on the machine in previous summers but said she has never received safety training. She noted that the cones have an image of a “hand and fingers chopped off.”

“From that, I would know I’m not supposed to put my fingers inside the cone.”

Araceli’s mother said that workers are afraid to complain about heat or other working conditions because they don’t want to be singled out as troublemakers. “They will say you are not doing your job and fire you,” the mother said in Spanish.

2,600 complaints for agricultural outdoor heat law violations were reported to the state.

Data from 2018 through Aug. 2024

Cal/OSHA

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

Even when workers do report employers, their complaints are not always investigated, according to a review of enforcement records for the Division of Occupational Safety and Health, known as Cal/OSHA.

Heat injury complaints

Cal/OSHA failed to investigate a majority of outdoor heat injury reports it received from agricultural employers.

Data from 2018 through Aug. 2024

Cal/OSHA

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

The division is responsible for ensuring worksite safety and enforcing California’s outdoor heat-illness law. The law was the first in the nation and was established two decades ago after years of pressure from the United Farm Workers and the deaths of several laborers in San Joaquin Valley fields.

The law requires heat-illness training for employees and protections such as providing break areas with shade and “pure, suitably cool” water as “close as practicable” to workers when temperatures exceed 80 degrees.

To analyze the agency’s enforcement performance, Capital & Main examined data from Cal/OSHA from 2015 through the first quarter of 2025. The analysis found that the agency failed to investigate most heat violation complaints and reports of heat injuries, and an overall 74% drop in violations issued to agricultural employers for all infractions.

Equipment used in the daily agricultural harvesting trade.

During that period, $32 million in fines were issued against agricultural employers statewide, but the agency collected less than half, or nearly $14.9 million.

Officials with the Department of Industrial Relations, which oversees Cal/OSHA, said that not all fines are collected because employers can appeal fines. The agency can also cut penalties in half if employers can document that violations have been corrected. But a state audit released in July found problems in the way the agency determines penalty amounts, resulting in smaller fines than other states issued for similar violations.

Agricultural worksite safety inspections

More than 630 agricultural inspections of all types were treated as letter investigations, meaning that officials never visited worksites and instead questioned employers by mail or phone.

Data from Cal/OSHA from 2015 through mid-October 2024

Lorena Iñiguez Elebee LOS ANGELES TIMES

Cal/OSHA also relied on “letter investigations” for 11% of its inspections of agricultural operations from 2015 to mid-October 2024. Officials also contend that letter investigations — in which worksites are not physically inspected after complaints are filed — allow the agency to reach a greater number of worksites and address more hazards in the shortest amount of time. In 2020, however, a Cal/OSHA consultant concluded that 10% of letter investigations resulted from personnel shortages and “should have elicited full on-site inspections.” In some letter investigations, according to the state audit, “Cal/OSHA lacked evidence to support its decision not to inspect.”

Monterroza, the department spokesperson, again blamed impacts of the pandemic for affecting the number of inspections. But she said the agency is taking other measures to improve worker safety.

These include aggressive employer outreach, she said, and the launch of a new agricultural unit “to strengthen enforcement, increase on-site inspections, and expand resources to better reach and protect workers” in areas such as El Centro, Salinas and Lodi.

The agency announced the unit in February 2024, but as of May, just 15 of the 54 positions budgeted for the unit had been filled, according to Cal/OSHA.

In the meantime, young workers like Jose, the Salinas Valley strawberry picker, will continue to labor in the fields.

He lives with nine siblings and their children in several small adobe-colored homes bounded by huge berry fields and a lot filled with battered vehicles.

The teenagers and adults in the family, some of whom emigrated from a small town in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, take whatever jobs are available — planting and picking berries, pulling weeds and removing old plastic tarps from the fields.

Jose and other strawberry pickers endure persistent pain in their lower backs, shoulders and legs during the harvest season. They sweat in the hot sun — often without shade — and slog along muddy rows when it rains.

“If I was in charge,” said Jose about children and teens in the fields, “I would not let them work just because they’re kids and not let them suffer at a young age.”

Lopez is an independent journalist and fellow at the McGraw Center for Business Journalism.