The seaside town was once ‘incredibly grim’ but now attracts visitors from across the world

Folkestone in Kent has traditionally been overshadowed by its bustling neighbour, Dover. Like many renowned seaside resorts across the UK, Folkestone thrived from the Edwardian era through to the 1950s and early 60s, as Brits flocked there before jetting off abroad became the norm.

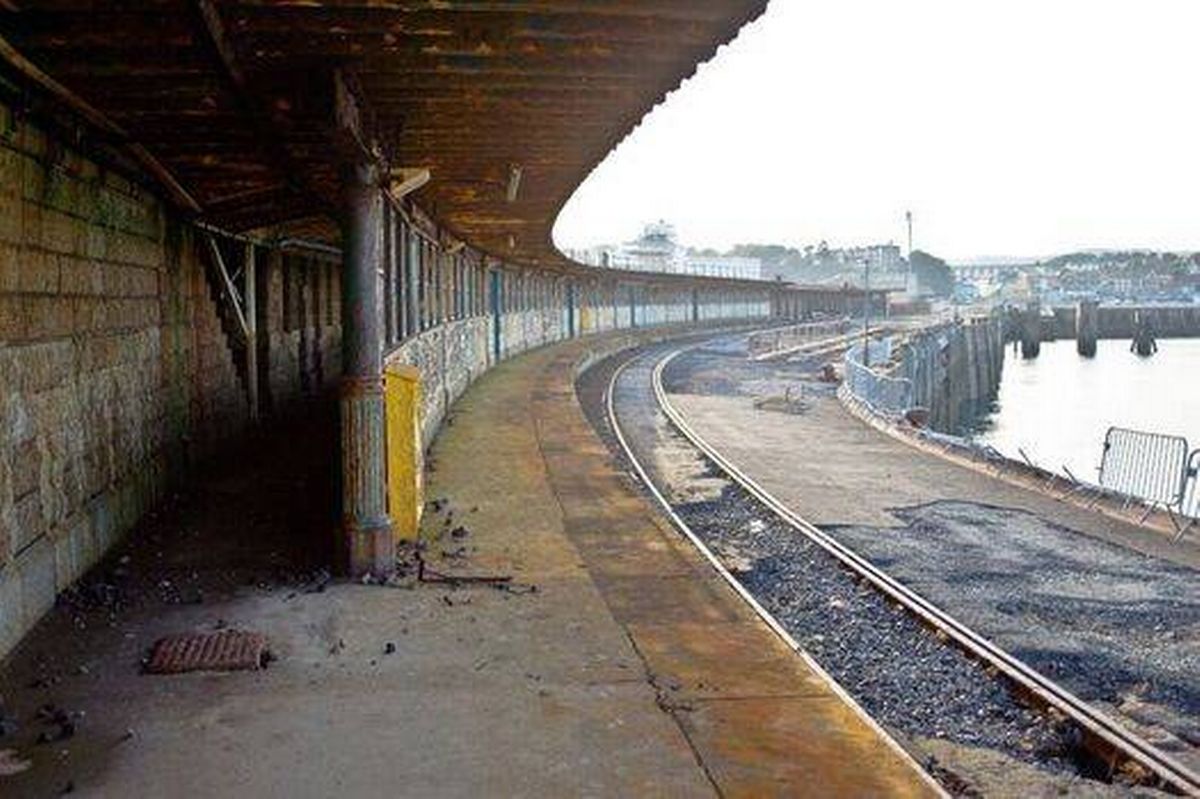

However, more recently, the town has experienced a downturn, with its ferry port closing in the early 2000s and the Channel Tunnel becoming the main route for travel between the UK and France. But one resident has made it his business to turn the town’s fortunes around.

Business tycoon Sir Roger De Haan, 75, who grew up in Folkestone and lived there until his teenage years, later sold his parents’ holiday business, Saga, and began pouring £100million into rejuvenating his hometown. “When I grew up in Folkestone as a teenager, there was nothing to do,” Sir Roger told the Express at the end of 2025.

READ MORE: I paid £106 for lunch at British music legend’s pub — I can sum it up in two wordsREAD MORE: UK town that’s started an accidental rivalry with New Zealand over steep street

“It was incredibly grim. Now, there’s an awful lot for kids to do, for families to do. Like many seaside towns in Britain, Folkestone went into decline, and I watched that happen. There used to be hundreds of hotels, and now there are a tiny number.

“I love the place. I grew up here. I worked in Folkestone. Saga’s headquarters were always in Folkestone. I had my kids in Folkestone. I’ve always lived in Folkestone, or the surrounding area. I do have an emotional attachment to it.”

The philanthropist paints a picture of how, when he began investing money into the area, much of it was a neglected “slum”, as a new town centre had pushed aside the old parts, which “declined more rapidly than everywhere else”.

Sir Roger’s father Sidney “predicted that tourists, once they discovered overseas holidays, would turn their back on Folkestone,” the entrepreneur recalls. “I think he would be really happy that, Folkestone, in a way, has been reinvented, and people have rediscovered it, and are returning in large numbers.”

Today, the resort’s Creative Quarter stands as a testament to its transformation into a fashionable tourist hotspot, home to 80 independent traders. It has drawn visitors from as far as east Asia, as well as numerous Londoners who have relocated permanently to the coast for a slower, more tranquil lifestyle.

Sir Roger recounts: “When I started this project, almost all of them [the shops] were empty. Some were boarded up, and most of them they didn’t even bother to board up.” He purchased around 90 “slum buildings”, and granted a 125-year lease for the properties to his arts charity for “a peppercorn rent”.

“Because of this formula,” he explains, “it should still be successful in 100 years’ time, because it hasn’t got a commercial landlord. It’s got a charity landlord who doesn’t have to pay anything for the rent.”

Additionally, Folkestone has benefited from significant investment in its educational provision and sporting amenities. The transformation is far from over, as the next contentious phase to redevelop the harbour – featuring tower blocks containing 1,000 homes and 10,000 square metres of commercial space – received approval in June.

Artist’s renderings of the sleek apartments planned around the harbour resemble something more commonly found in Dubai, Monte Carlo or perhaps trendy Brighton, further along the south coast.

And this has left some residents feeling uncomfortable. When Mike O’Donoughue, 67, who runs Plectrums and Paints in the Creative Quarter, first set foot in Folkestone two decades ago, the neighbourhood was “derelict”, though he now worries about the potential drawbacks of the town’s transformation.

“Brighton is scary, and I don’t think we really want to be heading that way here,” he says. “I think they could be a bit more lenient on the parking [in Folkestone] especially at weekends.”

Sir Roger reassures those concerned that he has no intention of transforming Folkestone into Brighton. He adds: “Folkestone has its own personality that’s unique. We’ve got the white cliffs. You can see France, you can see France quite often. It’s surrounded with lovely countryside. It’s a great place to live. It’s a great place to work. And, no, we’re not trying to turn it into some other place.”

Mr O’Donoughue also notes that some locals “feel like they’re being ousted, slightly”. He recalls how, 15 years ago, properties and flats were cheap. “And now it seems they’re in line with most other places along the coast,” the local added.

Data from Rightmove shows Folkestone house prices averaged £320,757 over the past year, significantly above the UK average property price of £265,000 recorded in June.

“One of the challenges with regeneration is that rents go up and house prices go up,” Sir Roger says. “But they needed to go up a bit because the housing stock in Folkestone was getting very, very rundown. And one of the reasons people weren’t investing in their rundown house… is when you’ve done up your house, you need to know it’s worth what you paid for it and how much you spent in doing it up.”

Steve Smith, 69, a church organist from the nearby village of Smeeth, observes: “There’s money, and there’s the millionaire’s flats along the front. But then you can see just looking around the place that there’s still huge poverty as well.”

His wife, Gianna Marchesi, 69, who works as a school caretaker, laments the disappearance of the resort’s traditional attractions. “It was actually quite fun, occasionally, to come down and enjoy it with the children, or without the children,” she reflects. “And the market on a Sunday was quite fun.”

Brian Frost, 64, a Folkestone native, shared his perspective. “It’s not what it was like when I was a kid,” he told the Express beside his beloved red 1990s Peugeot. He notes the town is now dominated by cafés, nail bars, hairdressers and betting shops.

Do you have a travel story to share? Email webtravel@reachplc.com