WNBA players call out officiating, but league trusts its process

With red welts scattered like landmarks of the war she’d just waged, Kelsey Plum let the microphone have it.

“I drive more than anyone in the league,” the Sparks guard said, voice taut. “So to shoot six free throws is f— absurd. And I got scratches on my face, I got scratches on my body, and these guards on the other teams get these ticky-tack fouls, and I’m sick of it.”

Plum played 41 minutes during an overtime loss to the Golden State Valkyries, during which she was awarded those six free throws. She is one of many WNBA players, coaches and fans who have vented frustration over what they see as inconsistent and unreliable officiating this season.

Yet, within the walls of the league’s officiating office, there is steadfast belief that referees are doing their jobs well.

Las Vegas Aces coach Becky Hammon questions a referee’s call during the game against the Sparks at Crypto.com Arena on July 29.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“Overall, I’m very pleased with the work this year,” said Monty McCutchen, the head of referee training and development for all NBA leagues.

But McCutchen and Sue Blauch, who oversees WNBA referee performance and development, aren’t blind to the backlash — acknowledging “some high-profile misses that we need to own on our end.”

To do so, they pointed to an officiating analysis program through which 95% of games are watched live, with every play graded by internal and independent reviewers. Those evaluations are used to chart each referee’s performance over time.

Teams can flag up to 30 plays for review per game through a league portal — including isolated calls or themes spanning multiple games. League officials respond with rulings on each clip and compile curated playlists by call type, delivering them directly to the referees.

“There’s no shortage of feedback,” McCutchen said.

But the WNBA’s structural backbone of officiating differs from the NBA in significant ways. With just 35 referees, all of whom moonlight calling NCAA or G League games, the WNBA relies on part-timers earning $1,538 per game as rookies, with each official calling 20 to 34 contests per season.

“You’re working three very different kinds of basketball,” said Jacob Tingle, director of sport management at Trinity University who has conducted research on officiating networks and pathways. “The reason the NBA or MLB works is because that’s all you do — you’re working the same kind of game only.”

The WNBA lacks a centralized replay center, a developmental league to groom talent and shuffles crew combinations from game to game — a patchwork system that can strain referees expected to deliver consistency.

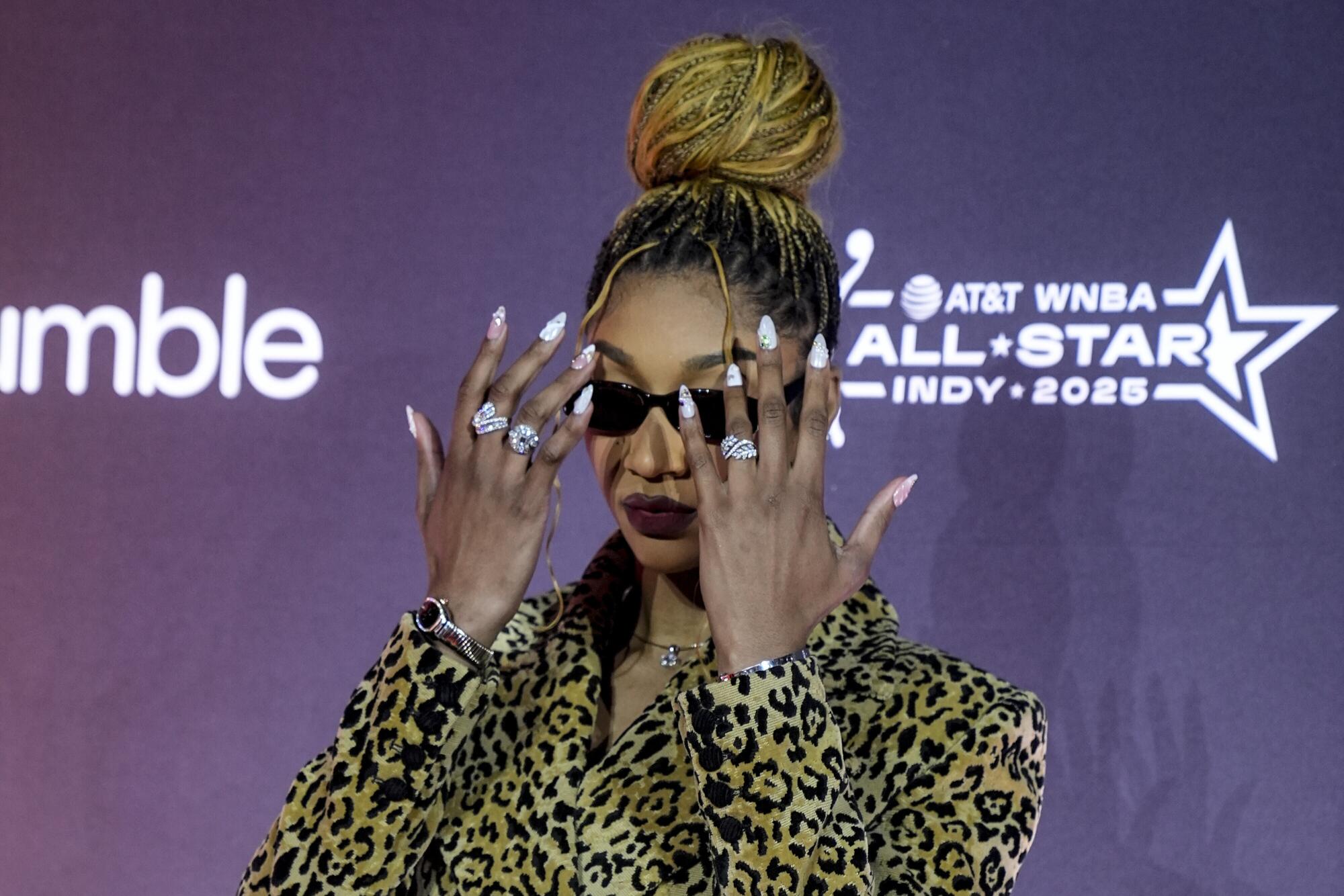

Sparks guard Kelsey Plum questions the official’s out-of-bounds call during a game against the Las Vegas Aces at Crypto.com Arena on July 29.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

“When you don’t have group cohesion, you don’t have the same level of trust in your partners,” said David Hancock, a professor who studies the psychology of sports officiating. “We’ve done one study — when referees felt more connected to their group, they also felt they performed better.”

McCutchen said teams get a verdict on the calls they send for review. But beyond that, there’s no insight into grading or transparency about patterns the league has researched. So when it seems a whistle has been swallowed during a game, players and coaches are left searching for consistency.

“You don’t know in the WNBA anymore,” said Joshua Jackson, a Louisiana State University professor who studies media and athlete perception. “I can’t tell when I’m watching a game exactly what this foul call is going to be. I’ll hear the whistle and think, ‘OK, maybe it’s a reach-in and then suddenly it’s a view for a flagrant one instead? Wait, how did we get here?’”

The whistle has become one of the WNBA’s biggest wild cards. Angel Reese called it “diabolical.” Lynx coach Cheryl Reeve said after a fourth-quarter letdown led to a loss that the game was “stolen from us.” Belgian guard Julie Allemand told The Times she felt more “protected” playing in EuroBasket. And Napheesa Collier, one of the stars of the 2025 season, warned “it’s getting worse.”

The whistle, or lack thereof, might echo louder in 2026, when the WNBA begins a $2.2-billion, 11-year media rights deal with Disney, Amazon and NBCUniversal — each of whom will air more than 125 games a year across TV and streaming networks.

Nicole LaVoi, who helms the Tucker Center — a research hub focused on advocating for girls and women in sports — said the narrative surrounding female athletes forces them to walk a tightrope: speak up and risk being dismissed as an emotional woman or stay quiet and let the league’s image unravel.

“This is a broader, contextual, systemic issue,” LaVoi said. “It’s not just about bad refs making bad calls. This is a much larger problem within a system where women’s sport has been undervalued and underappreciated for decades.”

Many players have ignored concerns about the perception they whine too much about officiating, arguing the inconsistency in calls is dangerous.

Lucas Seehafer, a professor and kinesiologist at Medical University of South Carolina who tracks WNBA injuries, said players have suffered 173 injuries this season and missed 789 games, entering Saturday’s games.

Sparks forward Cameron Brink reacts toward an official after no foul was called after the ball was stripped from her as she was driving to the basket at Crypto.com Arena on July 29.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

Injuries are undoubtedly multifactorial, Seehafer said. Still, inconsistent whistles can leave players unsure of how much contact to expect — forcing them into unfamiliar movements or hesitation. And that can lend itself to awkward landings, a key contributor in lower-extremity injuries.

“The athletes strive on consistency and mechanical efficiency,” said Nirav Pandya, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon and sports medicine specialist at UC San Francisco. “When you don’t know how much contact’s going to be allowed, it does throw off that rhythm, which increases your injury risk.”

When Caitlin Clark suffered a groin injury in mid-July, her brother — in a now-deleted X post — blamed the officials for letting too much contact slide.

“People go watch the WNBA because of the talent,” LaVoi said, “and when the talent is sitting on the bench, that’s not very exciting to fans.”

While critics are quick to call out officiating, referees are navigating a structure stretched thin.

Brenda Hilton, founder of Officially Human — an organization dedicated to improving the treatment of sports officials — said 70%-80% of officials quit within their first three years, largely due to online abuse.

“The people that are doing the work are people, they are fallible,” LaVoi said. “The players are fallible as well, so are the coaches. So can we get back some compassion for the humanity of the people doing it, and appreciate the fact that they love what they do? They’re not doing it because they’re getting huge NIL deals and branding opportunities.”

NBA and WNBA officiating leaders have not announced any plans for changes to their system, so the stress will probably continue among players, coaches, fans and those who control the whistles.