Method dressing: Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya, ‘Wicked’ fashions explained

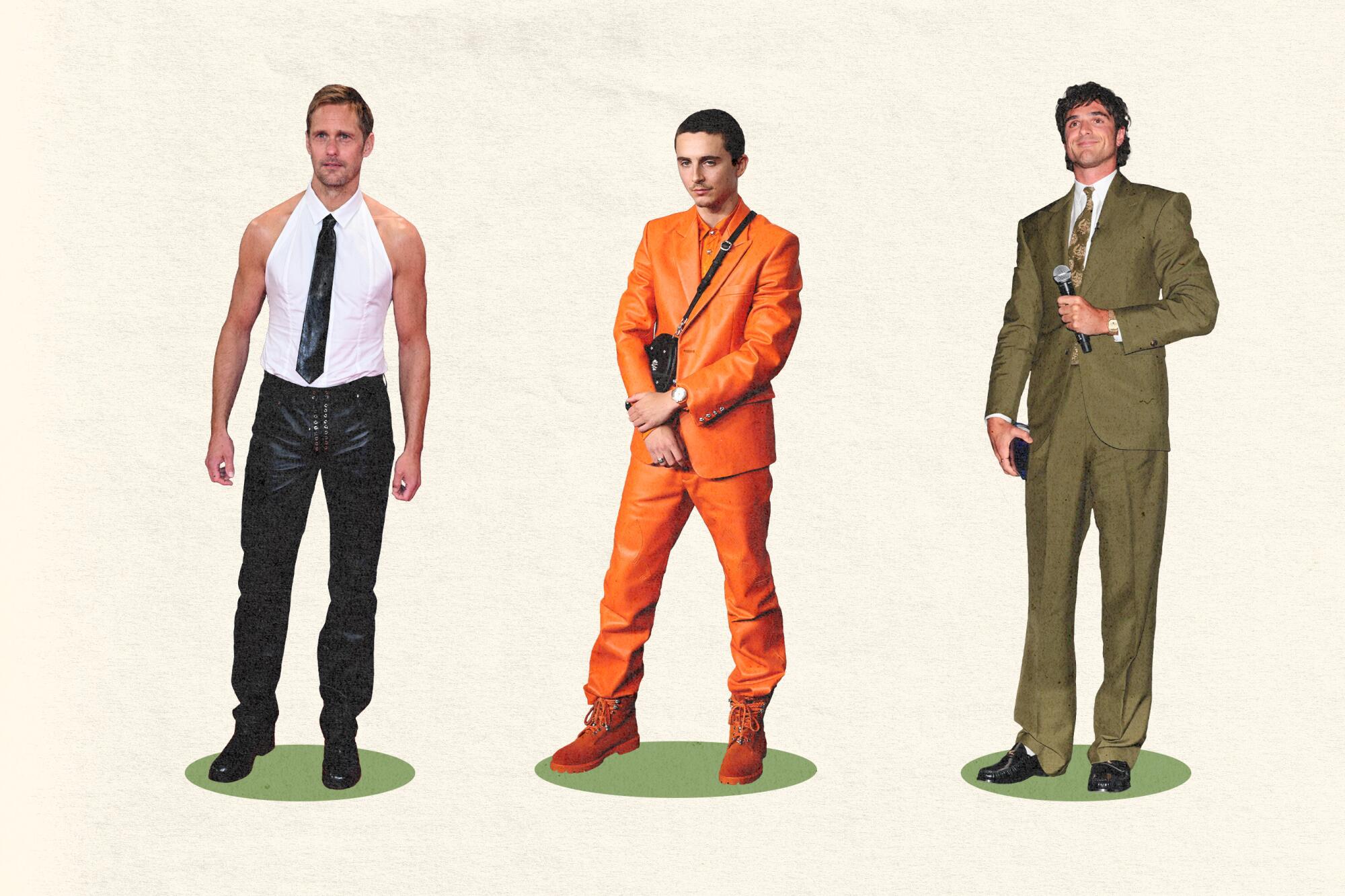

Cynthia Erivo’s aggressively feathered Balenciaga at the “Wicked: For Good” New York premiere. Alexander Skarsgård’s Ludovic de Saint Sernin halter top and snug leather pants at the London premiere of the BDSM dramedy “Pillion.” Jacob Elordi’s Celine suit — in monster green, no less — at the Newport Beach Film Festival as the actor promoted “Frankenstein.”

If these recent outings haven’t convinced you that Hollywood is in its method dressing era, well, where in the Law Roach have you been?

From left: “Pillion’s” Alexander Skarsgård, “Marty Supreme’s” Timothée Chalamet and “Frankenstein’s” Jacob Elordi.

(Photos by Getty Images)

For those not familiar, method dressing is when stars wear looks on a press tour inspired by the movie they’re promoting. The practice has been around since the days of Old Hollywood, when actors like Audrey Hepburn, in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and “Sabrina,” melded their star personas with their characters. More recently, Geena Davis and Gwyneth Paltrow channeled their projects with their premiere fits in the 1990s, and the casts of 2015’s “Cinderella” and 2018’s “Black Panther” did the same.

But experts say the current method dressing trend — exemplified by Margot Robbie’s Andrew Mukamal-styled candy-colored juggernaut for “Barbie,” Zendaya’s dystopian desert and tennis chic in her Law Roach-styled appearances for “Dune 2” and “Challengers,” and the relentless, two-year press tour for the “Wicked” movies — is a different animal.

“Method dressing often becomes prologue to the film itself — it sets the tone and the context of the film and makes you curious about it,” says Ross Martin, president of marketing agency Known. “[But it’s also] a signal that the actor you like really is deeply invested in this film. They’re not just showing up, they’re actually embodying the character in the world of the film.”

‘Wicked’ stars Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande.

(Photos by Getty Images)

Martin cites Timothée Chalamet’s orange-hued campaign for “Marty Supreme” as a particularly skillful deployment of the trend. “If your favorite actor keeps showing up in the same way over and over again, that used to be rewarded,” he says. “Now there’s this pressure on Hollywood stars to define and then redefine themselves … [you] don’t want to see the same Chalamet that [you] just saw playing Bob Dylan. What you’re seeing is really modern marketing tools applied in very strategic ways to the traditional medium of films. It’s really necessary because 90% of the movies that are released don’t get the marketing dollars they need to launch. So this is innovation by necessity.”

Savvy stylists are also driving the red carpet cosplay. “Previously, stylists were responsible for making sure that stars appeared on trend,” says Raissa Bretaña, fashion historian and lecturer at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology. “As they gained more prominence in the movie industry, it was less about making sure the stars were on trend and more about making sure the stars were setting the trends.”

Setting trends and creating meme-worthy, TikTok- and Instagram-friendly moments that often reach more eyeballs than the films themselves. An image of “a star wearing a beautiful gown isn’t enough anymore,” says Bretaña. “It is meant to engage with the algorithm. How do we get people talking more about this movie? How do we get more eyes on it by having a different manifestation of it in our real life?”

Indeed, during the “Challengers” press tour, online chatter peaked each time Zendaya stepped out in a new tennis-centric look. “I’m a storyteller, and the clothes are my words,” Zendaya’s stylist Law Roach recently said to Variety. As for his work with the actor on “Dune: Part Two” — including Thierry Mugler’s sartorial mic drop — Roach told Vogue the “looks served as an extension of the wardrobe from the movie; it was intentional and purposeful.”

Zendaya in outfits inspired by her movie “Challengers”

(Photos by Getty Images)

Pop culture commentator Blakely Thornton has been following method dressing closely, posting frequently on press tour fashions. “Maybe [Zendaya] walked so Cynthia and Ariana could run,” he says. “The stars are taking it upon themselves to be like, ‘I have to invest in myself in this capacity to get what I need out of it.’” It’s an important distinction, he notes, as film execs aren’t always footing the bill for stylists. “The studios are pretending that it’s not something they have to pay for when it’s something in the internet era you must require. Because if these people came out wearing a turtleneck to every premiere, you wouldn’t be happy.”

Enrique Melendez, the stylist behind Jenna Ortega’s viral red carpet looks for the “Beetlejuice Beetlejuice” press tour, believes his work was key in boosting interest for new demographics. “Jenna being of a newer generation, wearing pieces and looks celebrating the original film had a whole new wave of young people researching the references and Easter eggs with their parents who understood exactly what they meant.”

Still, you can’t guarantee virality: There’s a fine line between a “Spider-Man” triumph and a “Madame Web” tragedy. Some of it can be attributed to an actor’s commitment, says Martin, contrasting Chalamet’s enthusiastic campaign with Dakota Johnson’s reluctant “Madame Web” tour. It also depends on the film itself. Bretaña says method dressing tends to work best with sci-fi or fantasy projects because of the inherent drama in their costuming.

She’s excited by an upcoming period film, Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of “Wuthering Heights,” starring on-theme veterans Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi. “I think ‘Wuthering Heights’ will be our litmus test to see if method dressing will spill over into historically inspired garments,” says Bretaña. “In the past, whenever actors promoted period films, they try to look as contemporary as possible in order to distance themselves.”

Actors actually looking like themselves on the red carpet? Groundbreaking.