Vanessa Gordon, from New York, was not expecting to find love when she took a post-divorce trip to Tuscany – the home of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli, Donatello and Giotto

Vanessa Gordon was just 18 when she got married, and 37 when she got divorced.

After 13 years of marriage, the mum was understandably unsure about her next move. Fortunately, her friends were not.

“My friends had a WhatsApp group entitled Vanessa 2.0, where they would encourage me to get out there and enjoy myself. That was the kind of headspace I was in when I went out to Tuscany, a little bit delicate and fragile and in need of some encouragement to start the next phase of my life,” she told the Mirror.

The event planner and producer, from the Hamptons in New York, travelled to the Italian region, which as the home of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli, Donatello and Giotto is synonymous with beauty.

It was there that she had a chance encounter with a stranger who would change her life.

READ MORE: Event dubbed ‘best new thing to do in the world’ moves to nunnery

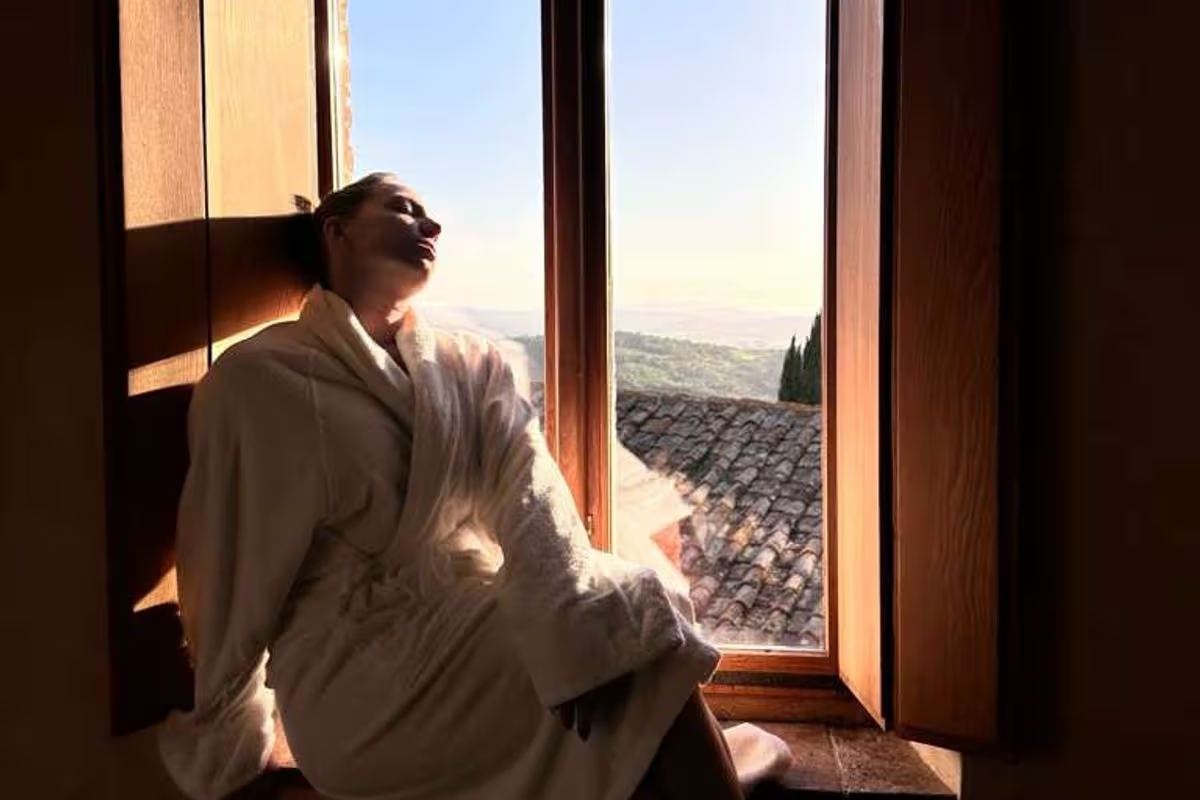

Vanessa was staying in a hotel when a man in his early 20s walked past her, smiled, winked and disappeared. “He was absolutely gorgeous. My hair was in a messy bun, and I was in a bathrobe, but I knew there was something between us,” she explained.

She relayed the encounter to her friends, who joked that Italian men were just like that and suggested she should not dwell on it. Maybe it was the romantic setting, or maybe there was something about this mysterious man. Vanessa was convinced there was something there. “I had a gut feeling about him. It took me back to being sweet 16,” she said.

Later that same day, Vanessa was having dinner in the hotel with her friends when she spotted the same young man. After her friends’ insistence, she approached him. She asked him about the drinks menu, and he asked her her name.

“Vanessa. Beautiful,” he said, before winking and walking away.

The response bowled the American over. “I’ll never forget it,” she said. Later that evening, after hours of dining and chatting, the mysterious staff member reappeared and asked if he could place a blanket over her shoulders to keep out the chill of the night. She said yes.

Although their interactions had been fleeting and communication across languages difficult, by the end of dinner Vanessa was sad to discover that he had finished work. She had meant to give him her number but did not get the chance before he slipped away.

Luckily, his name was printed on the meal’s bill. Vanessa found him on social media, added him and hoped. Within moments, he accepted and messaged her, asking when she was leaving. “Tomorrow,” Vanessa replied, regretfully informing the Italian waiter that she would be heading to Florence in the morning.

“He said he would come to Florence to see me, and I thought, ‘yeah right’, but that’s what he did.”

The waiter did not just make the two-and-a-half-hour train ride to Florence. He spent two days by Vanessa’s side, walking around the city, chatting constantly and taking it all in.

“What I found so fascinating was that my nerves instantly melted away when we met and started talking. I felt totally at ease with him, and I still can’t believe looking back that he was only the second man I had ever been with, even into my mid-30s. I think that’s very special and very rare,” she explained.

“I was very impressed by how mature he is and how hard he tried to speak English, while I spoke the best Italian I could. We used a translator every now and then. I didn’t mind that he smoked, which surprised me. He was very confident, but not in an arrogant way.

“We didn’t do too many touristy things. We went to dinner at a local sushi spot, visited Piazzale Michelangelo and spent a lot of time walking and talking. We ended the last evening watching one of his favourite films in Italian with English subtitles.

“I trusted him as well. We were completely alone together and I felt fine.”

At the end of the two days, Vanessa told the former stranger she had to return to New York, while he needed to go back to work. They kissed and went their separate ways.

“I can’t believe it happened. It was so special at that time in my life. My friends went from cheering me on to living vicariously through me. They said I lived a moment most people could only dream of. It set me up for everything else I’ve done since then. It was perfect,” she said.

It is not clear what lies ahead for Vanessa and the Italian waiter, who did meet again when she returned to Europe. Regardless, she looks back on the chance encounter with love and as the beginning of a new chapter.

“He helped me get my belief back in myself and build my confidence. It made me realise everyone is in this together, everyone gets nervous or uncertain. We’re all just people. My confidence has reignited now. I’m a totally new woman, and he was the start of that,” she said.

“And no matter what happens in the future, he will always hold a special place in my heart.”

Do you have a story to share? Email webtravel@reachplc.com