Are vaccine mandates needed to achieve high vaccination rates? | Health News

US states have relied on vaccine mandates since the 1800s, when a smallpox vaccine offered the first successful protection against a disease that had killed millions.

More than a century later, Florida’s top public health official said vaccine requirements are unethical and unnecessary for high vaccination rates.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

“You can still have high vaccination numbers, just like the other countries who don’t do any mandates like Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the [United Kingdom], most of Canada,” Florida Surgeon General Dr Joseph Ladapo said on October 16. “No mandates, really comparable vaccine uptake.”

It’s true that some countries without vaccine requirements have high vaccination rates, on a par with the United States. But experts say that fact alone does not make it a given that the US would follow the same pattern if it eliminates school vaccination requirements.

Florida state law currently requires students in public and private schools from daycare through 12th grade to have specific immunisations. Families can opt out for religious or medical reasons. About 11 percent of Florida kindergarteners are not immunised, recent data shows. With Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s backing, Ladapo is pushing to end the state’s school vaccine requirements.

The countries Ladapo cited – Sweden, Norway, Denmark, the UK and parts of Canada – don’t have broad vaccine requirements, research shows. Their governments recommend such protections, though, and their healthcare systems offer conveniently accessible vaccines, for example.

UNICEF, a United Nations agency which calls itself the “global go-to for data on children”, measures how well countries provide routine childhood immunisations by looking at infant access to the third dose in a DTaP vaccine series that protects against diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (whooping cough).

In 2024, UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that 94 percent of one-year-olds in the United States had received three doses of the DTaP vaccine. That’s compared with Canada at 92 percent, Denmark at 96 percent, Norway at 97 percent, Sweden at 96 percent and the UK at 92 percent.

Universal, government-provided healthcare and high trust in government likely influence those countries’ vaccine uptake, experts have said. In the US, many people can’t afford time off work or the cost of a doctor’s visit. There’s also less trust in the government. These factors could prevent the US from having similar participation rates should the government eliminate school vaccine mandates.

Universal healthcare, stronger government trust increase vaccination

Multiple studies have linked vaccine mandates and increased vaccination rates. Although these studies found associations between the two, the research does not prove that mandates alone cause increased vaccination rates. Association is not the same as causation.

Other factors that can affect vaccination rates often accompany mandates, including local efforts to improve vaccination access, increase documentation and combat vaccine hesitancy and refusal.

The countries Ladapo highlighted are high-income countries with policies that encourage vaccination and make vaccines accessible.

In Sweden, for example, where all vaccinations are voluntary, the vaccines included in national programmes are offered for free, according to the Public Health Agency of Sweden.

Preventive care is more accessible and routine for everyone in countries such as Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK with universal healthcare systems, said Dr Megan Berman of the University of Texas Medical Branch’s Sealy Institute for Vaccine Sciences.

“In the US, our healthcare system is more fragmented, and access to care can depend on insurance or cost,” she said.

More limited healthcare access, decreased institutional trust and anti-vaccine activists’ influence set the US apart from those other countries, experts said.

Some of these other countries’ cultural norms favour the collective welfare of others, which means people are more likely to get vaccinated to support the community, Berman said.

Anders Hviid, an epidemiologist at Statens Serum Institut in Copenhagen, told The Atlantic that it’s misguided to compare Denmark’s health situation with the US – in part because Danish citizens strongly trust the government to enact policies in the public interest.

By contrast, as of 2024, fewer than one in three people in the US over age 15 reported having confidence in the national government, according to data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, a group of advanced, industrialised nations. That’s the lowest percentage of any of the countries Ladapo mentioned.

“The effectiveness of recommendations depends on faith in the government and scientific body that is making the recommendations,” said Dr Richard Rupp, of the University of Texas Medical Branch’s Sealy Institute for Vaccine Sciences.

Without mandates, vaccine education would be even more important, experts say

Experts said they believe US vaccination rates would fall if states ended school vaccine mandates.

Maintaining high vaccination rates without mandates would require health officials to focus on other policies, interventions and messaging, said Samantha Vanderslott, the leader of the Oxford Vaccine Group’s Vaccines and Society Unit, which researches attitudes and behaviour towards vaccines.

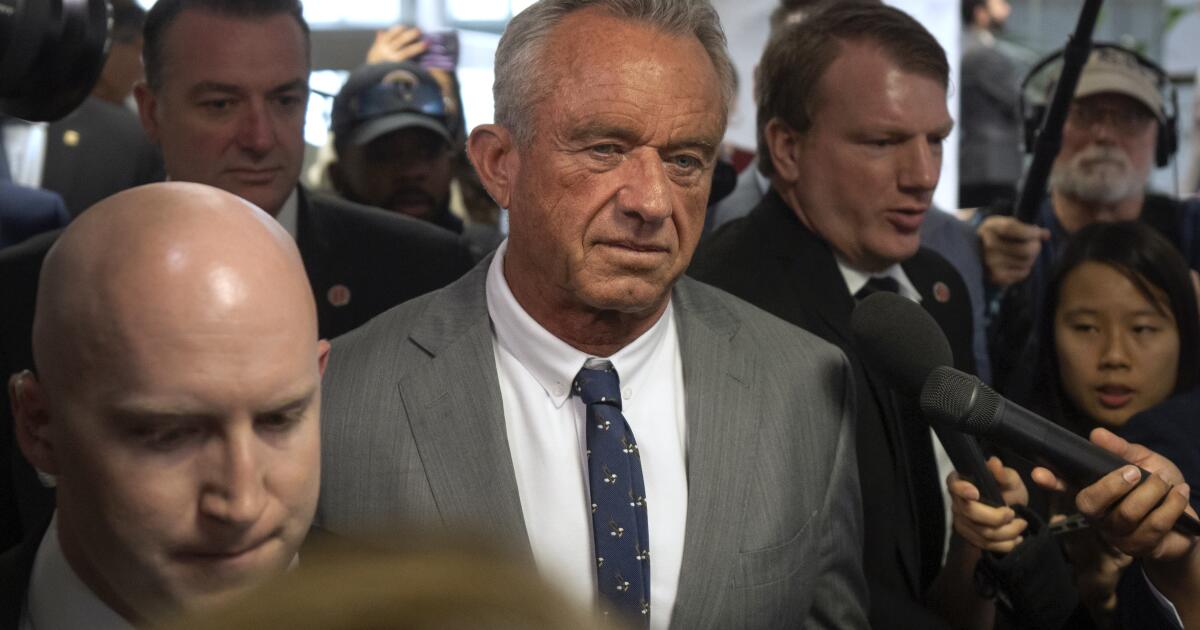

That could be especially difficult given that the United States’s top health official, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F Kennedy Jr, has a long history of anti-vaccine activism and scepticism about vaccines.

That makes the US an outlier, Vanderslott said.

“Governments tend to promote/support vaccination as a public health good,” she said. It is unusual for someone with Kennedy’s background to hold a position where he has the power to spread misinformation, encourage vaccine hesitancy and reduce mainstream vaccine research funding and access, Vanderslott said.

Most people decide to follow recommendations based on their beliefs about a vaccine’s benefits and their child’s vulnerability to disease, Rupp said. That means countries that educate the public about vaccines and illnesses will have better success with recommendations, he said.

Ultimately, experts said that just because something worked elsewhere doesn’t mean it will work in the United States.

Matt Hitchings, a biostatistics professor at the University of Florida’s College of Public Health and Health Professions, said a vaccine policy’s viability could differ from country to country. Vaccination rates are influenced by a host of factors.

“If I said that people in the UK drink more tea than in the US and have lower rates of certain cancers, would that be convincing evidence that drinking tea reduces cancer risk?” Hitchings said.

Google Translate was used throughout the research of this story to translate websites and statements into English.