U.S. seeks to assert its control over Venezuelan oil with tanker seizures and sales worldwide

WASHINGTON — President Trump’s administration on Wednesday sought to assert its control over Venezuelan oil, seizing a pair of sanctioned tankers transporting petroleum and announcing plans to relax some sanctions so the U.S. can oversee the sale of Venezuela’s petroleum worldwide.

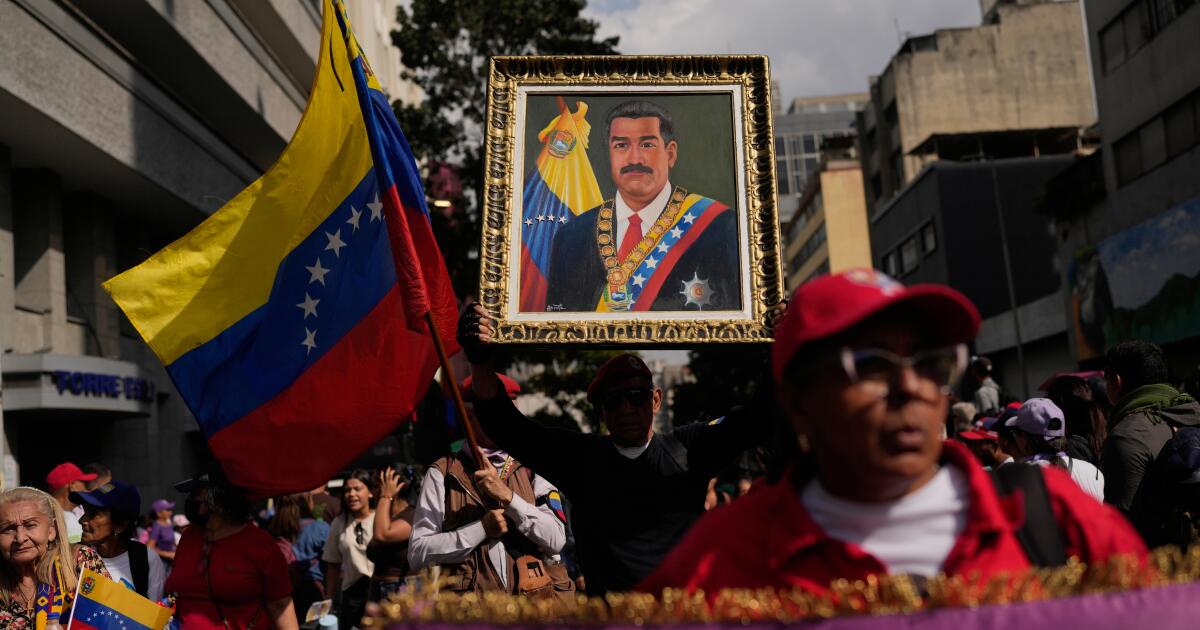

Trump’s administration intends to control the distribution of Venezuela’s oil products globally following its ouster of President Nicolás Maduro in a surprise nighttime raid. Besides the United States enforcing an existing oil embargo, the Energy Department says the “only oil transported in and out of Venezuela” will be through approved channels consistent with U.S. law and national security interests.

That level of control over the world’s largest proven reserves of crude oil could give the Trump administration a broader hold on oil supplies globally in ways that could enable it to influence prices. Both moves reflect the Republican administration’s determination to make good on its effort to control the next steps in Venezuela through its vast oil resources after Trump has pledged the U.S. will “run” the country.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio suggested that the oil taken from the sanctioned vessels seized in the North Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea would be sold as part of the deal announced by Trump on Tuesday under which Venezuela would provide up to 50 million barrels of oil to the U.S.

“One of those ships that was seized that had oil in the Caribbean, you know what the interim authorities are asking for in Venezuela?” Rubio told reporters after briefing lawmakers Wednesday about the Maduro operation. “They want that oil that was seized to be part of this deal. They understand that the only way they can move oil and generate revenue and not have economic collapse is if they cooperate and work with the United States.”

Seizing 2 more vessels

U.S. European Command said on social media that the merchant vessel Bella 1 was seized in the North Atlantic for “violations of U.S. sanctions.” The U.S. had been pursuing the tanker since last month after it tried to evade a blockade on sanctioned oil vessels around Venezuela.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem revealed U.S. forces also took control of the M Sophia in the Caribbean Sea. Noem said on social media that both ships were “either last docked in Venezuela or en route to it.”

The two ships join at least two others that were taken by U.S. forces last month — the Skipper and the Centuries.

The Bella 1 had been cruising across the Atlantic nearing the Caribbean on Dec. 15 when it abruptly turned and headed north, toward Europe. The change in direction came days after the first U.S. tanker seizure of a ship on Dec. 10 after it had left Venezuela carrying oil.

When the U.S. Coast Guard tried to board the Bella 1, it fled. U.S. European Command said a Coast Guard vessel had tracked the ship “pursuant to a warrant issued by a U.S. federal court.”

As the U.S. pursued it, the Bella 1 was renamed Marinera and flagged to Russia, shipping databases show. A U.S. official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive military operations, said the ship’s crew had painted a Russian flag on the side of the hull.

The Russian Foreign Ministry said it had information about Russian nationals among the Marinera’s crew and, in a statement carried by Russia’s state news agencies Tass and RIA Novosti, demanded that “the American side ensure humane and dignified treatment of them, strictly respect their rights and interests, and not hinder their speedy return to their homeland.”

Separately, a senior Russian lawmaker, Andrei Klishas, decried the U.S. action as “blatant piracy.”

The Justice Department is investigating crew members of the Bella 1 vessel for failing to obey Coast Guard orders and “criminal charges will be pursued against all culpable actors,” Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi said.

“The Department of Justice is monitoring several other vessels for similar enforcement action — anyone on any vessel who fails to obey instructions of the Coast Guard or other federal officials will be investigated and prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law,” Bondi said on X.

The ship had been sanctioned by the U.S. in 2024 on allegations of smuggling cargo for a company linked to Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, which is backed by Iran.

Easing sanctions so U.S. can sell oil

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is “selectively” removing sanctions to enable the shipping and sale of Venezuelan oil to markets worldwide, according to an outline of the policies published Wednesday by the Energy Department.

The sales are slated to begin immediately with 30 million to 50 million barrels of oil. The U.S. government said the sales “will continue indefinitely,” with the proceeds settling in U.S.-controlled accounts at “globally recognized banks.” The money would be disbursed to the U.S. and Venezuelan populations at the “discretion” of Trump’s government.

Venezuelan state-owned oil company PDVSA said it is in negotiations with the U.S. government for the sale of crude oil.

“This process is developed under schemes similar to those in force with international companies, such as Chevron, and is based on a strictly commercial transaction, with criteria of legality, transparency and benefit for both parties,” the company said in the statement.

The U.S. plans to authorize the importation of oil field equipment, parts and services to increase Venezuela’s oil production, which has been roughly 1 million barrels a day.

The Trump administration has indicated it also will invest in Venezuela’s electricity grid to increase production and the quality of life for people in Venezuela, whose economy has been unraveling amid changes to foreign aid and cuts to state subsidies, making necessities, including food, unaffordable to millions.

Ships said to be part of a shadow fleet

Noem said both seized ships were part of a shadow fleet of rusting oil tankers that smuggle oil for countries facing sanctions, such as Venezuela, Russia and Iran.

After the seizure of the now-named Marinera, which open-source maritime tracking sites showed was between Scotland and Iceland earlier Wednesday, the U.K. defense ministry said Britain’s military provided support, including surveillance aircraft.

“This ship, with a nefarious history, is part of a Russian-Iranian axis of sanctions evasion which is fueling terrorism, conflict, and misery from the Middle East to Ukraine,” U.K. Defense Secretary John Healey said.

The capture of the M Sophia, on the U.S. sanctions list for moving illicit cargos of oil from Russia, in the Caribbean was much less prolonged.

The ship had been “running dark,” not having transmitted location data since July. Tankers involved in smuggling often turn off their transponders or broadcast inaccurate data to hide their locations.

Samir Madani, co-founder of TankerTrackers.com, said his organization used satellite imagery and surface-level photos to document that at least 16 tankers had left the Venezuelan coast since Saturday, after the U.S. captured Maduro.

The M Sophia was among them, Madani said, citing a recent photo showing it in the waters near Jose Terminal, Venezuela’s main oil export hub.

Windward, a maritime intelligence firm that tracks such vessels, said in a briefing to reporters the M Sophia loaded at the terminal on Dec. 26 and was carrying about 1.8 million barrels of crude oil — a cargo that would be worth about $108 million at current price of about $60 a barrel.

The press office for Venezuela’s government did not immediately respond to an Associated Press request for comment on the seizures.

Toropin, Boak, Lawless and Biesecker write for the Associated Press. Lawless reported from London.