Newly released satellite images show that Iran has recently built a concrete shield over a new facility at a sensitive military site and covered it in soil, advancing work at a location reportedly bombed by Israel in 2024 amid soaring tensions with the United States and the threat of regional war.

The images also show that Iran has buried tunnel entrances at a nuclear site bombed by Washington during Israel’s 12-day war with Iran last year – which the US joined on Israel’s behalf – fortified tunnel entrances near another, and has repaired missile bases struck in the conflict.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

They offer a rare glimpse of Iranian activities at some of the sites at the centre of tensions with Israel and the US.

Some 30km (20 miles) southeast of Tehran, the Parchin complex is one of Iran’s most sensitive military sites. Western intelligence has suggested Tehran carried out tests relevant to nuclear bomb detonations there more than 20 years ago. Iran has always denied seeking atomic weapons and says its nuclear programme is purely for civilian purposes.

Neither US intelligence nor the UN nuclear watchdog found any evidence last year that Iran was pursuing nuclear weapons.

Israel reportedly struck Parchin in October 2024. Satellite imagery taken before and after that attack shows extensive damage to a rectangular building at Parchin, and apparent reconstruction in images from November 6, 2024. Imagery from October 12, 2025, shows development at the site, with the skeleton of a new structure visible and two smaller structures adjacent to it.

Progress is apparent in imagery from November 14, with what appears to be a metallic roof covering the large structure. By February 16, it cannot be seen at all, hidden by what experts say is a concrete structure.

The Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), in a January 22 analysis of satellite imagery, pointed to progress in the construction of a “concrete sarcophagus” around a newly built facility at the site, which it identified as Taleghan 2.

ISIS founder David Albright wrote on X: “Stalling the negotiations has its benefits: Over the last two to three weeks, Iran has been busy burying the new Taleghan 2 facility … More soil is available and the facility may soon become a fully unrecognizable bunker, providing significant protection from aerial strikes.”

The institute also reported in late January that satellite images showed new efforts to bury two tunnel entrances at the Isfahan complex – one of the three Iranian uranium-enrichment plants bombed by the US in June during the war. By early February, ISIS said all entrances to the tunnel complex were ”completely buried”.

Other images point to ongoing efforts since February 10 to “harden and defensively strengthen” two entrances to a tunnel complex under a mountain some 2km (1.2 miles) from Natanz – the site that holds Iran’s other two uranium enrichment plants.

This comes as Washington seeks to negotiate a deal with Tehran on its nuclear programme while threatening military action if talks fail.

On Tuesday, US and Iranian representatives reached an understanding on main “guiding principles” during a meeting in Geneva, but felt short of achieving any breakthrough. The meeting in the Swiss city came after a first round of talks in Oman on February 6.

Reports suggest that Tehran would make detailed proposals in the next two weeks to close gaps. Among the many hurdles in the negotiations is the US push to widen the scope of the deal to include restrictions on Iran’s ballistic arsenal and support for its allies in the region.

That is fuelled by Israel’s demands and regional narrative, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu repeatedly pressing US President Donald Trump to shift from nuclear-only parameters.

Tehran has insisted that these provisions are non-negotiable but that it is open to discuss curbs on its nuclear programme in exchange for sanctions relief.

A previous negotiating effort collapsed last year when Israel launched attacks on Iran, triggering the 12-day war that Washington joined in by bombing key Iranian nuclear sites.

As diplomacy forges a path, both parties are ramping up military pressure.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) held a series of war games on Monday and Tuesday in the Strait of Hormuz to prepare for “potential security and military threats”.

On Wednesday, Tehran announced new joint naval drills with Russia in the Sea of Oman. Rear Admiral Hassan Maqsoudlou said the exercises were aimed at preventing any unilateral action in the region, and enhancing coordination against threats to maritime security, including risks to commercial vessels and oil tankers.

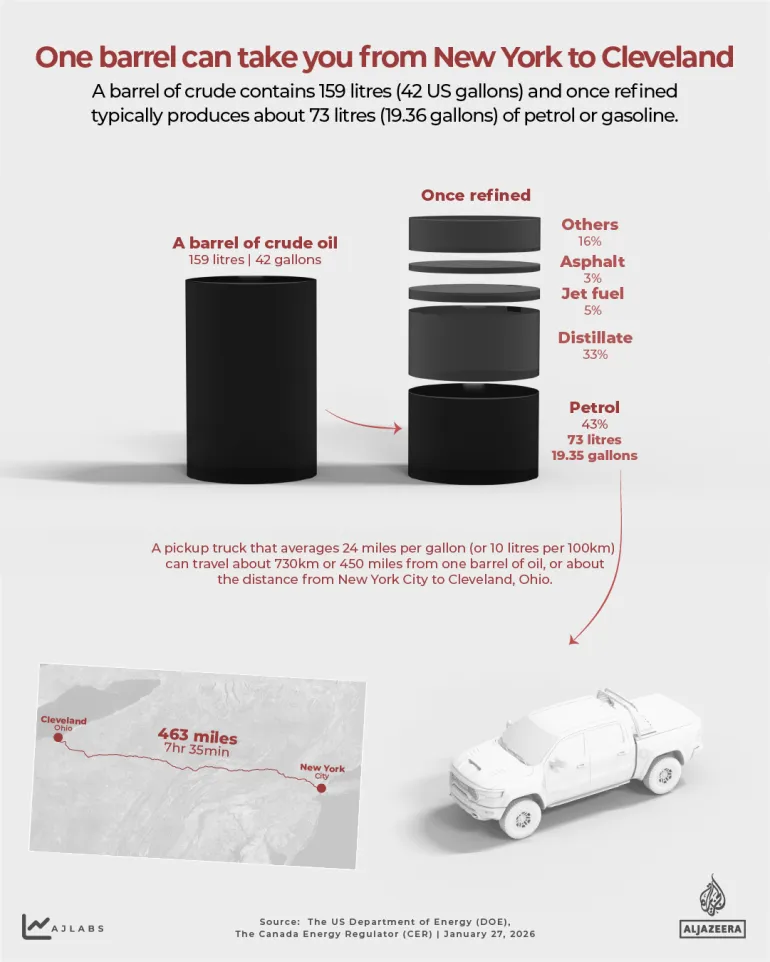

The US has also escalated its military build-up in the region. Trump has ordered a second aircraft carrier to the region, with the first, the USS Abraham Lincoln and its nearly 80 aircraft, positioned about 700 kilometres (435 miles) from the Iranian coast as of Sunday, according to satellite imagery.

The Trump administration also issued new threats against Tehran with White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt saying on Wednesday that “Iran would be very wise to make a deal” with the US. Trump escalated his rhetoric on social media.

“Should Iran decide not to make a Deal,” the US may need to use an Indian Ocean airbase in the Chagos Islands, “in order to eradicate a potential attack by a highly unstable and dangerous Regime”, he wrote on his Truth Social platform.