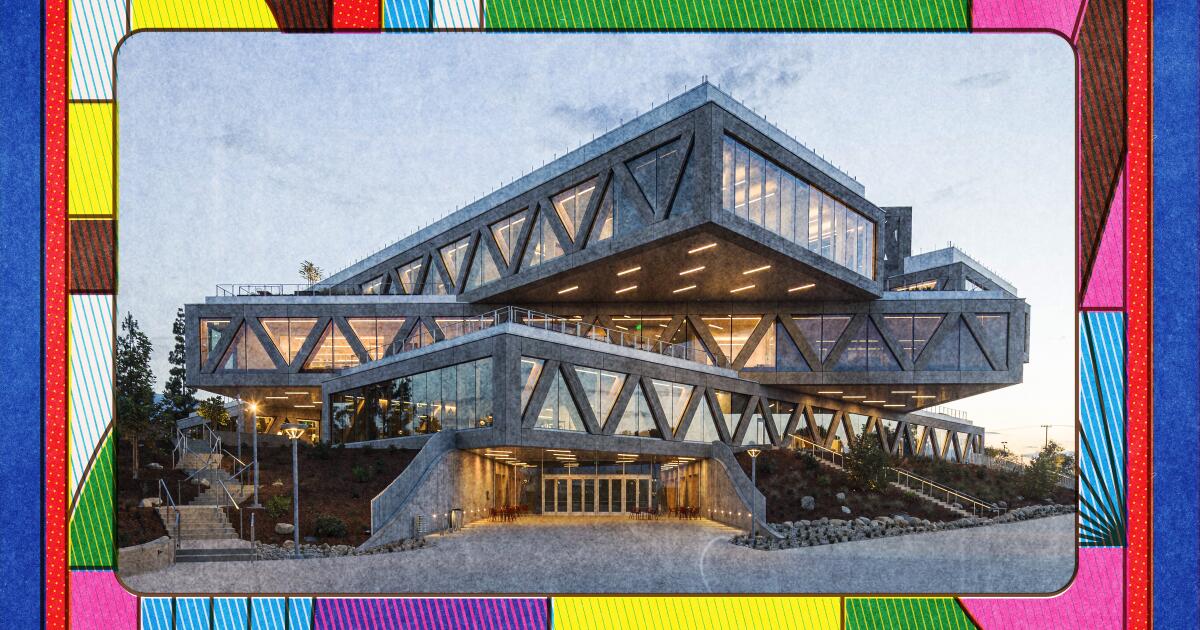

7 best L.A. architecture projects of 2025

The best of Los Angeles architecture in 2025 felt like attractive experiments with an uncanny sense of the future. They include micro-scaled production studios to a high school completed in two months after the Palisades fire to the mammoth LAX Metro Transit Center.

Source link