Seoul, Brasília Elevate Ties with Strategic Minerals and Trade Pact

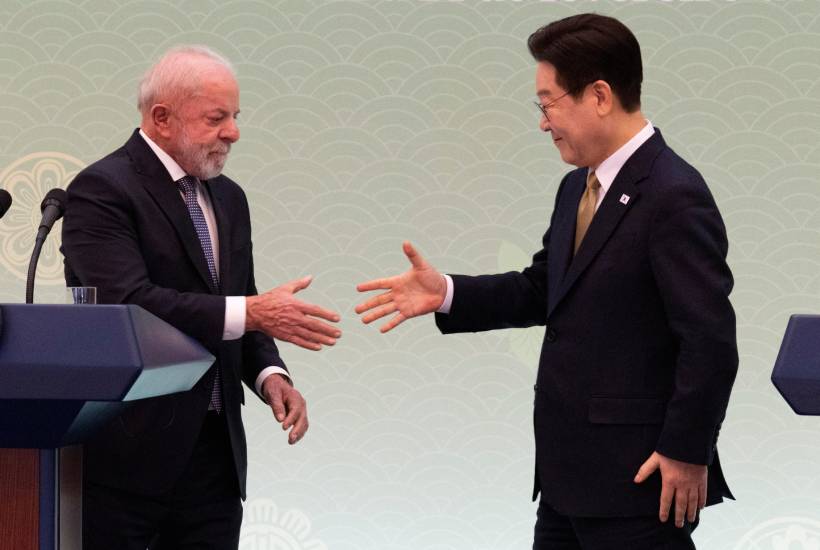

South Korea and Brazil have agreed to significantly deepen cooperation across key minerals, trade, technology and security, as President Lee Jae Myung hosted Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Seoul for the first Brazilian state visit in more than two decades. The summit, held at the Blue House, marked a symbolic reset in bilateral ties and produced an ambitious roadmap aimed at elevating relations to a strategic partnership.

The two leaders endorsed a four-year action plan designed to anchor cooperation in strategic minerals, advanced manufacturing, defence, space industries and food security. They also oversaw the signing of 10 memorandums of understanding covering trade and industrial policy, rare earths and other critical minerals, the digital economy including artificial intelligence, biotechnology and health, agricultural collaboration, small-business exchanges, and joint efforts to combat cybercrime and narcotics trafficking.

Critical Minerals at the Core

At the heart of the agreement lies a shared recognition of the growing geopolitical importance of critical minerals. Brazil holds significant reserves of rare earth elements and nickel, both essential to electric vehicles, renewable energy systems and high-tech manufacturing. South Korea, a manufacturing powerhouse heavily reliant on imported raw materials, is seeking to diversify supply chains amid intensifying global competition for resource security.

For Seoul, closer ties with Brasília offer an opportunity to secure stable access to strategic inputs while reducing exposure to concentrated supply routes. For Brazil, the partnership represents a chance to attract South Korean investment into mining, processing and downstream industries, potentially moving up the value chain rather than remaining primarily a raw-material exporter.

Trade Expansion and Industrial Policy Alignment

Brazil is South Korea’s largest trading partner in South America, and both governments signaled an intent to broaden the scope of commerce beyond traditional commodity flows. Industrial policy coordination featured prominently in the discussions, suggesting a shift toward co-development in sectors such as semiconductors, batteries and green technologies.

The emphasis on the digital economy and artificial intelligence reflects a convergence of economic strategies. South Korea’s advanced technological ecosystem complements Brazil’s expanding digital market, creating potential for joint ventures and technology transfers. Cooperation in biotech and health also indicates a recognition of demographic and public health challenges that transcend borders.

Security, Stability and Shared Democratic Narratives

Beyond economics, the leaders framed their partnership within a broader narrative of stability and democratic resilience. Lee emphasized support for peace on the Korean Peninsula, while Lula underscored Brazil’s interest in a balanced and rules-based international order.

Their personal rapport, shaped by shared experiences of early-life factory work and social mobility, added a human dimension to the diplomacy. Lee publicly praised Lula’s life story as emblematic of democratic progress, reinforcing a symbolic alignment that may help sustain political goodwill between the two administrations.

The inclusion of joint policing initiatives against cybercrime and transnational threats signals that the partnership extends into non-traditional security domains. As digital connectivity deepens, cyber resilience and coordinated law enforcement become integral to safeguarding economic integration.

Strategic Diversification in a Fragmented World

The timing of the summit is notable. As global trade faces renewed uncertainty and supply chains continue to recalibrate, middle powers such as South Korea and Brazil are seeking to hedge against volatility by strengthening bilateral and regional ties. By formalizing cooperation in minerals, technology and defence, both governments aim to insulate their economies from external shocks while positioning themselves within emerging industrial ecosystems.

The ceremonial elements of the visit including a state banquet blending Korean and Brazilian cultural traditions underscored the leaders’ intent to broaden engagement beyond transactional trade. Whether the newly signed agreements translate into measurable investment flows and industrial integration will depend on sustained political commitment and private-sector participation. Yet the framework established in Seoul suggests that both countries see strategic partnership not as a symbolic upgrade, but as a practical response to an increasingly fragmented global landscape.

With information from Reuters.