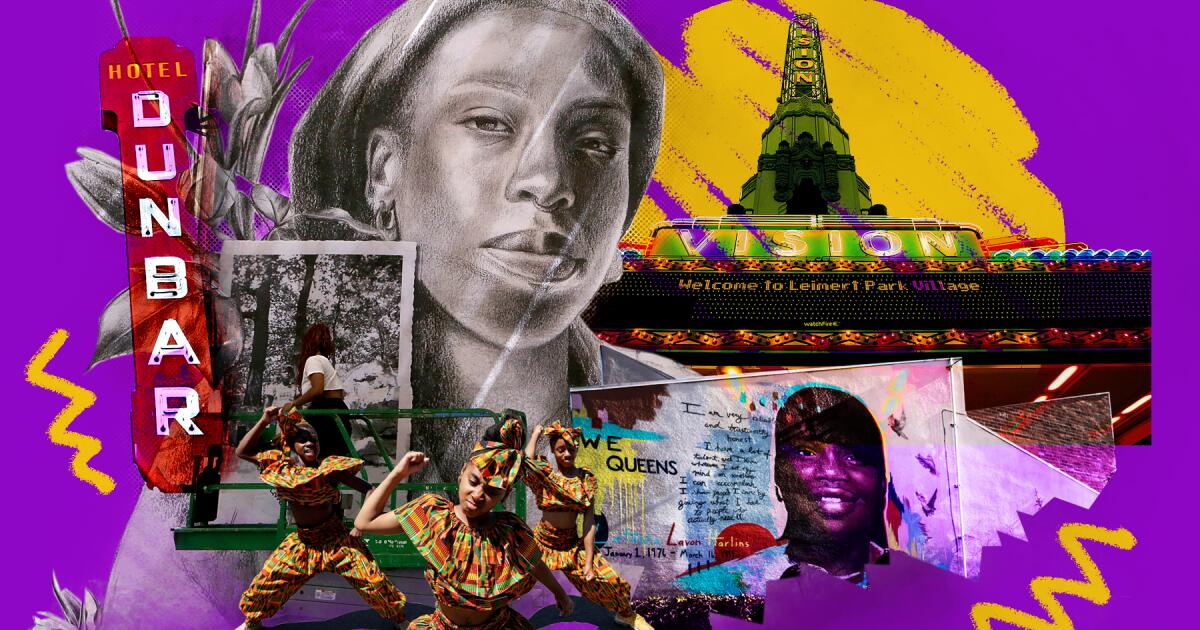

South L.A. just became a Black cultural district. Where should the monument go?

For more than a century, South Los Angeles has been an anchor for Black art, activism and commerce — from the 1920s when Central Avenue was the epicenter of the West Coast jazz scene to recent years as artists and entrepreneurs reinvigorate the area with new developments such as Destination Crenshaw.

Now, the region’s legacy is receiving formal recognition as a Black cultural district, a landmark move that aims to preserve South L.A.’s rich history and stimulate economic growth. State Sen. Lola Smallwood-Cuevas (D-Los Angeles), who led the effort, helped secure $5.5 million in state funding to support the project, and last December the state agency California Arts Council voted unanimously to approve the designation. The district, formally known as the Historic South Los Angeles Black Cultural District, is now one of 24 state-designated cultural districts, which also includes the newly added Black Arts Movement and Business District in Oakland.

Prior to this vote, there were no state designations that recognized the Black community — a realization that made Smallwood-Cuevas jump into action.

“It was very frustrating for me to learn that Black culture was not included,” said Smallwood-Cuevas, who represents South L.A. Other cultural districts include L.A.’s Little Tokyo and San Diego’s Barrio Logan Cultural District, which is rooted in Chicano history. Given all of the economic and cultural contributions that South L.A. has made over the years through events like the Leimert Park and Central Avenue jazz festivals and beloved businesses like Dulan’s on Crenshaw and the Lula Washington Dance Theatre, Smallwood-Cuevas believed the community deserved to be recognized. She worked on this project alongside LA Commons, a non-profit devoted to community-arts programs.

Beyond mere recognition, Smallwood-Cuevas said the designation serves as “an anti-displacement strategy,” especially as the demographics of South L.A. continue to change.

“Black people have experienced quite a level of erasure in South L.A.,” added Karen Mack, founder and executive director of LA Commons. “A lot of people can’t afford to live in areas that were once populated by us, so to really affirm our history, to affirm that we matter in the story of Los Angeles, I think is important.”

The Historic South L.A. Cultural District spans roughly 25 square miles, situated between Adams Boulevard to the north, Manchester Boulevard to the south, Central Avenue to the east and La Brea Avenue to the west.

Now that the designation has been approved, Smallwood-Cuevas and LA Commons have turned their attention to the monument — the physical landmark that will serve as the district’s entrance or focal point — trying to determine whether it should be a gateway, bridge, sculpture or something else. And then there’s the bigger question: Where should it be placed? After meeting with organizations like the Black Planners of Los Angeles and community leaders, they’ve narrowed their search down to eight potential locations including Exposition Park, Central Avenue and Leimert Park, which received the most votes in a recent public poll that closed earlier this month.

As organizers work to finalize the location for the cultural district’s monument by this summer, we’ve broken down the potential sites and have highlighted their historical relevance. (Please note: Although some of the sites are described as specific intersections, such as Jefferson and Crenshaw boulevards, organizers think of them more as general areas.)