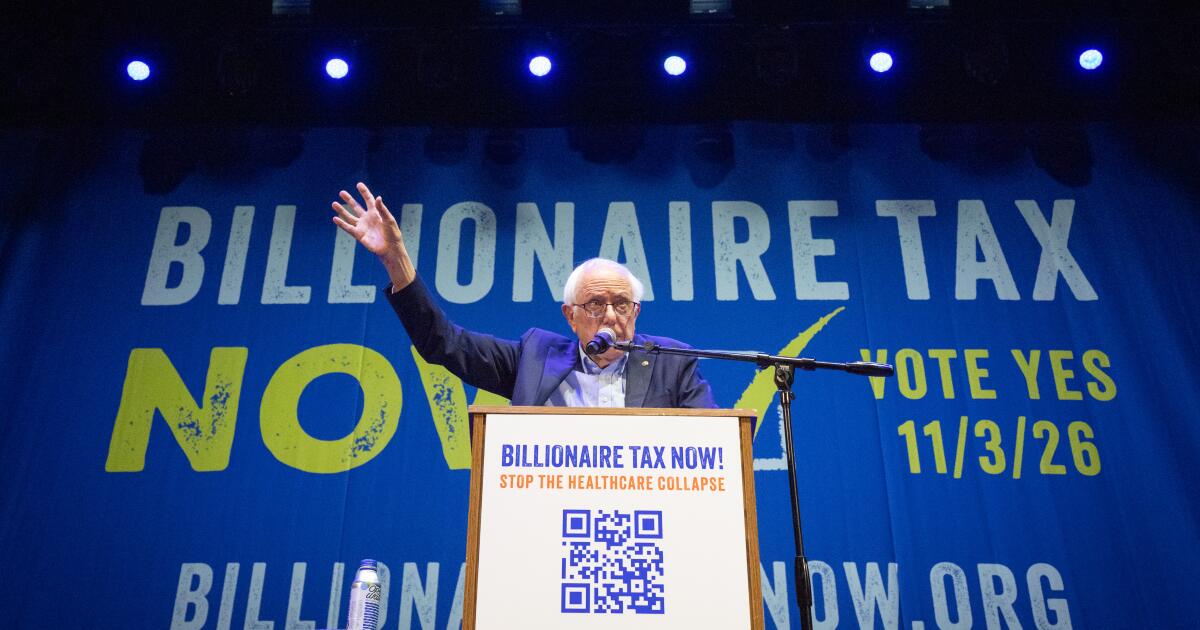

Bernie Sanders formally kicks off California wealth tax campaign

Populist Sen. Bernie Sanders on Wednesday formally kicked off the campaign to place a billionaires tax on the November ballot, framing the proposal as something larger than a debate about economic and tax policy as he appeared at a storied Los Angeles venue.

“The billionaire class no longer sees itself as part of American society. They see themselves as something separate and apart, like the oligarchs,” he told about 2,000 people at the Wiltern. The independent senator from Vermont compared them to kings, queens and czars of yore who believed they had a divine right to rule.

These billionaires “have created huge businesses with revolutionary technologies like AI and robotics that are literally transforming the face of the Earth,” he said, “and they are saying to you and to everybody in America, who the hell do you think you are telling us what we — the ruling elite, the millionaires, the billionaires, the richest people on Earth — who do you think you are telling us what we can do or not?”

California voters can show the billionaires “that we are still living in a democratic society where the people have some power,” Sanders said.

The senator is promoting a labor union’s proposal to impose a one-time 5% tax on the assets of California billionaires and trusts to backfill federal healthcare funding cuts by the Trump administration. Supporters of the contentious effort began gathering voter signatures to place the measure on the November ballot earlier this year. Sanders previously endorsed the proposal on social media and in public statements, and said he would seek to create a national version of the wealth tax.

But Wednesday’s event, a rally that lasted more than two hours and featured a lengthy performance by Rage Against the Machine guitarist Tom Morello, was framed as the formal launch of the campaign.

“Some people are free to choose between five-star restaurants, while others choose which dumpster will provide their next meal,” Morello said. “Some are free to choose between penthouse suites, while others are free to choose in which gutter to lay their heads.”

The guitarist’s comments came amid a set that included Rage’s protest song “Killing in the Name” and Bruce Springsteen’s social justice ballad “The Ghost of Tom Joad.”

“The people who’ve changed the world in progressive, radical or even revolutionary ways,” Morello said, “did not have any more money, power, courage, intelligence or creativity than anyone here tonight.”

Milling about outside the Wiltern, a historic Art Deco venue, were workers being paid $10 per signature they gathered to help qualify the proposal for the November ballot. Inside, attendees heard from labor leaders, healthcare workers and others whose lives are being affected by federal funding cuts to healthcare.

Lisandro Preza said he was speaking not only only as a leader of Unite Here Local 11, which represents more than 32,000 hospitality workers, but also as someone who has AIDS and recently lost his medical coverage.

“For me, this fight is very personal. Without my health coverage, the thought of going to the emergency room is terrifying,” he said. “That injection I rely on costs nearly $10,000 a month. That shot keeps my disease under control. Without it, my health, my life, are at risk, and I’m not alone. Millions of Americans are facing the same after massive federal healthcare cuts are putting our hospitals on the brink of collapse.”

Sanders, who punctuated his remarks with historic statistics about wealth in the United States and anecdotes about billionaires’ purchases of multiple yachts and planes, tied the impending healthcare cuts to broader problems of growing income and wealth inequality; the consolidation of corporate ownership, including over media outlets; the decline in workers’ wages despite increased productivity; and the threats to the job market of artificial intelligence and automation. He said all these issues were grounded in the greed of the nation’s wealthiest residents.

“For these people, enough is never enough,” he said. “They are dedicated to accumulating more and more wealth and power … no matter how many low-income and working-class people will die because they no longer have health insurance.”

“Shame! Shame!” the audience screamed.

In addition to the wealth tax event, Sanders also plans to use his time in California to meet with tech leaders and speak on Friday at Stanford University about the effects of artificial intelligence and automation on American workers alongside Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Fremont).

Millions of California voters deeply support the Vermont senator, who won the state’s 2020 Democratic presidential primary over Joe Biden by eight points, and narrowly lost the 2016 Democratic primary to Hillary Clinton.

Sanders were the first presidential candidate Elle Parker, 30, ever cast a ballot for in a presidential election.

“He’s inspired me,” said the podcaster, who lives in East Hollywood. “I just love the way he uses his words to inspire us all.”

Supporters proposed the wealth tax to make up for the massive federal funding cuts to healthcare that Trump signed last year. The California Budget & Policy Center estimates that as many as 3.4 million Californians could lose Medi-Cal coverage, rural hospitals could shutter, and other healthcare services would be slashed unless a new funding source is found.

But the tax proposal is controversial, creating a notable schism among the state’s Democrats because of concerns that it will prompt an exodus of the state’s wealthy, who are the major source of revenue that buttresses California’s volatile budget.

Gov. Gavin Newsom is among the Democrats who oppose it, as is San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan, who is among the dozen candidates running to replace the termed-out governor.

Mahan argued that the proposal had already hurt the state’s finances by driving economic investment and tax revenue out of California to tax-friendly environs.

“We need ideas that are sound, not just political proposals that sound good,” he said. “The answer is to close the federal tax loopholes the ultra-wealthy use to escape paying their fair share and invest those funds in paying down our debt, rebuilding our infrastructure, and protecting our most vulnerable families from skyrocketing healthcare premiums. The only winners in this proposal are the workers and taxpayers of Florida and Texas, who will take our jobs and benefit from the capital and tax revenue California is losing.”

A group affiliated with the governor plans to run digital ads opposing the proposal featuring Newsom along with other politicians on both sides of the aisle, as first reported by the New York Times.

The proposal has received more expected and unified backlash from the state’s conservatives and business leaders, who have launched ballot measures that could nullify part if not all of the proposed wealth tax. This is dependent on which, if any, of the measures qualify for the ballot — the number of votes each receives in November compared to the labor effort.

Silicon Valley billionaires, notably PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel and venture capitalist David Sacks — both major Trump supporters — announced they had already decamped California because of the effort.

Rob Lapsley, president of California Business Round Table, added that if the wealth tax is approved, it would destroy the state’s innovation economy, destabilize tax revenue and ultimately result in all Californians paying higher taxes.

“Let’s be clear — this $100-billion tax increase isn’t just a swipe at California’s most successful entrepreneurs; it’s a tax no one can afford because it weakens the entire economic ecosystem that supports jobs, investment, wages, and public services for everyday Californians,” he said. “When high earners leave, the cost doesn’t vanish — it lands on everyone through fewer jobs, less investment, and a weaker tax base — a recipe for new and higher taxes for everyone.”