Review: Hildegard von Bingen was a saint, an abbess, a mystic, a pioneering composer and is now an opera

Opera has housed a long and curious fetish for the convent. Around a century ago, composers couldn’t get enough of lustful, visionary nuns. Although relatively tame next to what was to follow, Puccini’s 1918 “Suor Angelica” revealed a convent where worldly and spiritual desires collide.

But Hindemith’s “Sancta Susanna,” with its startling love affair between a nun and her maid servant, titillated German audiences at the start of the roaring twenties, and still can. A sexually and violently explicit production in Stuttgart last year led to 18 freaked-out audience members requiring medical attention — and sold-out houses.

Los Angeles Opera got in the act early on. A daring production of Prokofiev’s 1927 “The Fiery Angel,” one of the operas that opened the company’s second season in 1967, saw, wrote Times music critic Martin Bernheimer, “hysterical nuns tear off their sacred habits as they writhe climactically in topless demonic frenzy.”

Now we have, as a counterbalance to a lurid male gaze as the season’s new opera for L.A. Opera’s 40th anniversary season, Sarah Kirkland Snider’s sincere and compelling “Hildegard,” based on a real-life 12th century abbess and present-day cult figure, St. Hildegard von Bingen. The opera, which had its premiere at the Wallis on Wednesday night, is the latest in L.A. Opera’s ongoing collaboration with Beth Morrison Projects, which commissioned the work.

Elkhanah Pulitzer’s production is decorous and spare. Snider’s slow, elegantly understated and, within bounds, reverential opera operates as much as a passion play as an opera. Its concerns and desires are our 21st century concerns and desires, with Hildegard beheld as a proto-feminist icon. Its characters and music so easily traverse a millennium’s distance that the High Middle Ages might be the day before yesterday.

Hildegard is best known for the music she produced in her Rhineland German monastery and for the transcriptions of her luminous visions. But she has also attracted a cult-like following as healer with an extensive knowledge of herbal remedies some still apply as alternative medicine to this day, as she has for her remarkable success challenging the patriarchy of the Roman Catholic Church.

She has further reached broad audiences through Oliver Sacks’ book, “Migraine,” in which the widely read neurologist proposed that Hildegard’s visions were a result of her headaches. Those visions, themselves, have attained classic status. Recordings of her music are plentiful. “Lux Vivens,” produced by David Lynch and featuring Scottish fiddle player Jocelyn Montgomery, must be the first to put a saint’s songs on the popular culture map.

Margarethe von Trotta made an effective biopic of Hildegard, staring the intense singer Barbara Sukowa. An essential biography, “The Woman of Her Age” by Fiona Maddocks, followed Hildegard’s canonization by Pope Benedict XVI in 2012.

Snider, who also wrote the libretto, focuses her two-and-a-half-hour opera, however, on but a crucial year in Hildegard’s long life (she is thought to have lived to 82 or 83). A mother superior in her 40s, she has found a young acolyte, Richardis, deeply devoted to her and who paints representations of Hildegard’s visions. Those visions, as unheard-of divine communion with a woman, draw her into conflict with priests who find them false. But she goes over the head of her adversarial abbot, Cuno, and convinces the Pope that her visions are the voice of God.

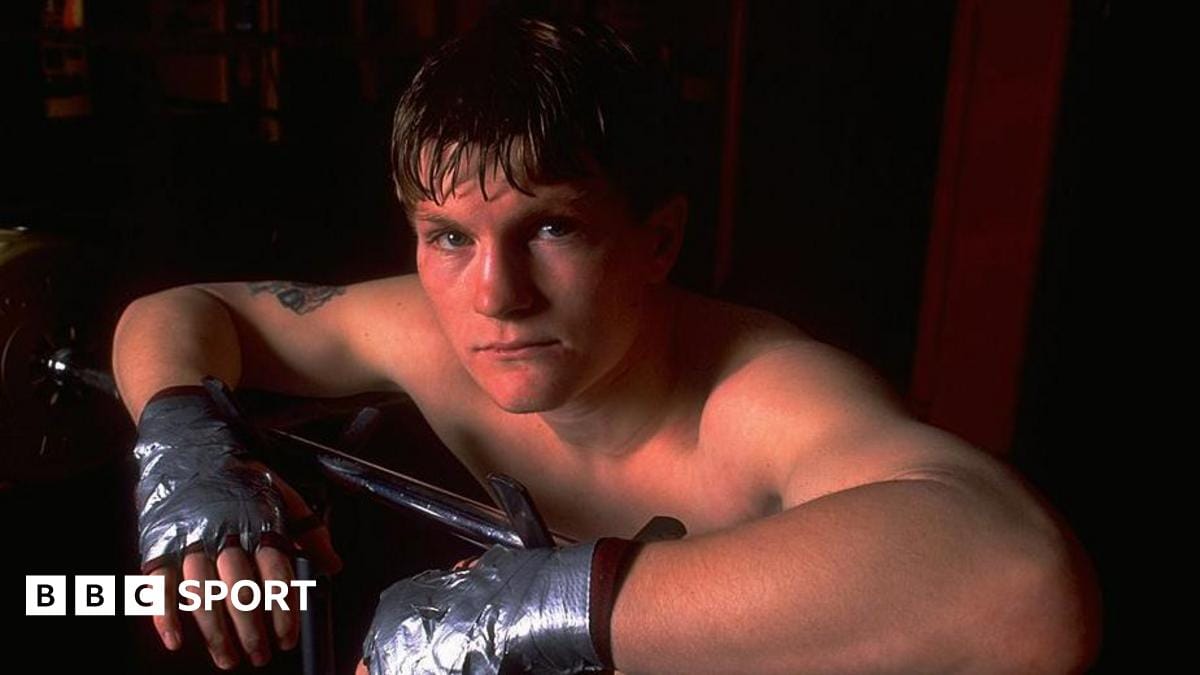

Mikaela Bennett, left, as Richardis von Stade and Nola Richardson as Hildegard von Bingen during a dress rehearsal of “Hildegard.”

(Carlin Stiehl / For The Times)

Hildegard, as some musicologists have proposed, may have developed a romantic attachment to the young Richardis, and Kirkland turns this into a spiritual crisis for both women. A co-crisis presents itself in Hildegard’s battles with Cuno, who punishes her by forbidding her to make music, which she ignores.

What of music? Along with being convent opera, “Hildegard” joins a lesser-known peculiar genre of operas about composers that include Todd Machover’s “Schoenberg in Hollywood,” given by UCLA earlier this year, and Louis Andriessen’s perverse masterpiece about a fictional composer, “Rosa.” In these, one composer’s music somehow conveys the presence and character of another composer.

Snider follows that intriguing path. “Hildegard” is scored for a nine-member chamber ensemble — string quartet, bass, harp, flute, clarinet and bassoon — which are members of the L.A. Opera Orchestra. Gabriel Crouch, who serves as music director, is a longtime member of the early music community as singer and conductor. But the allusions to Hildegard’s music remain modest.

Instead, each short scene (there are nine in the first act and five — along with entr’acte and epilogue — in the second), is set with a short instrumental opening. That may be a rhythmic, Steve Reich-like rhythmic pattern or a short melodic motif that is varied throughout the scene. Each creates a sense of movement.

Hildegard’s vocal writing was characterized by effusive melodic lines, a style out-of-character with the more restrained chant of the time. Snider’s vocal lines can feel, however, more conversational and more suited to narrative outline. Characters are introduced and only gradually given personality (we don’t get much of a sense of Richardis until the second act). Even Hildegard’s visions are more implied than revealed.

Under it all, though, is an alluring intricacy in the instrumental ensemble. Still with the help of a couple angels in short choral passages, a lushness creeps in.

The second act is where the relationship between Hildegard and Richardis blossoms and with it, musically, the arrival of rapture and onset of an ecstasy more overpowering than Godly visions. In the end, the opera, like the saint, requires patience. The arresting arrival of spiritual transformation arrives in the epilogue.

Snider has assembled a fine cast. Outwardly, soprano Nola Richardson can seem a coolly proficient Hildegard, the efficient manager of a convent and her sisters. Yet once divulged, her radiant inner life colors every utterance. Mikaela Bennett’s Richardis contrasts with her darker, powerful, dramatic soprano. Their duets are spine-tingling.

Tenor Roy Hage is the amiable Volmar, Hildegard’s confidant in the monastery and baritone David Adam Moore her tormentor abbot. The small roles of monks, angels and the like are thrilling voices all.

Set design (Marsha Ginsberg), light-show projection design (Deborah Johnson), scenic design, which includes small churchly models (Marsha Ginsberg), and various other designers all function to create a concentrated space for music and movement.

All but one. Beth Morrison Projects, L.A. Opera’s invaluable source for progressive and unexpected new work, tends to go in for blatant amplification. The Herculean task of singing five performances and a dress rehearsal of this demanding opera over six days could easily result in mass vocal destruction without the aid of microphones.

But the intensity of the sound adds a crudeness to the instrumental ensemble, which can be all harp or ear-shatter clarinet, and reduces the individuality of singers’ voices. There is little quiet in what is supposed to be a quiet place, where silence is practiced.

Maybe that’s the point. We amplify 21st century worldly and spiritual conflict, not going gentle into that, or any, good night.

‘Hildegard’

Where: The Wallis, 9390 N. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills

When: Through Nov. 9

Tickets: Performances sold out, but check for returns

Info: (213) 972-8001, laopera.org

Running time: About 2 hours and 50 minutes (one intermission)