Gaza mother recognises missing son on Israeli ‘for sale’ post | Newsfeed

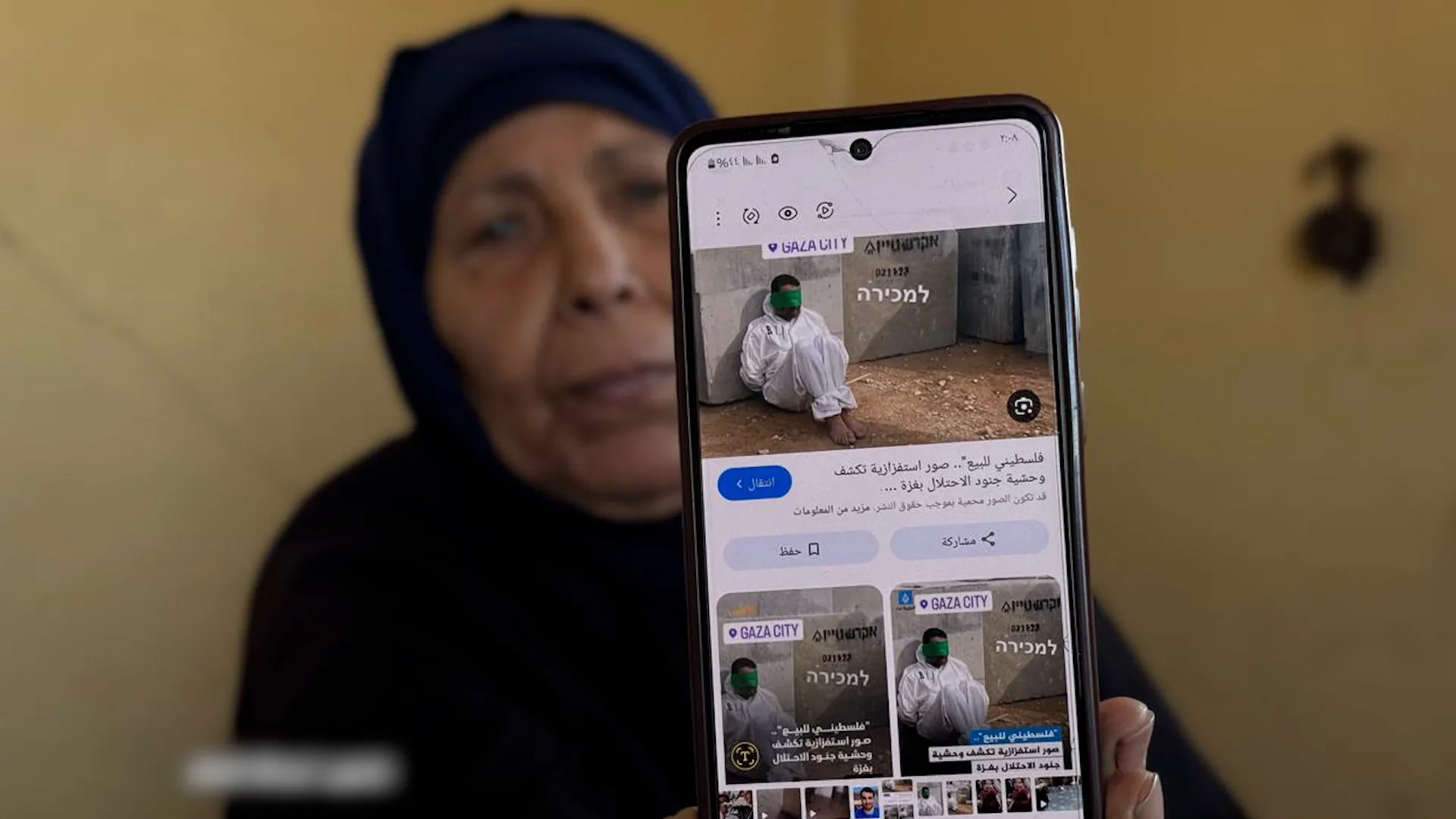

A Palestinian mother from Gaza says she recognised her missing son, Mohammed Sharab, when he was shown shackled, blindfolded and listed as ‘for sale’ in a post shared by Israeli soldiers.

Published On 26 Feb 2026