West Hollywood poet laureate’s nature program turns high schoolers into authors

The late afternoon sun was setting over Coldwater Canyon when the bus arrived. Students from Boyle Heights’ Bravo High spilled out into TreePeople, a nature reserve and nonprofit in Coldwater Canyon Park, and took off hiking.

As they looked around the sage and monkeyflower-lined path, their chatter quieted, and soon, they were writing poetry.

Alina Sadibekova, a junior at the magnet medical school, sat under native oak trees, breathing in the soil-rich air with a pen in hand.

“Our city is very busy, especially living in L.A. where everything just goes on and on and it feels like there’s never a point where we can take a breath,” Alina said. “Going to the parks helped me ground myself.”

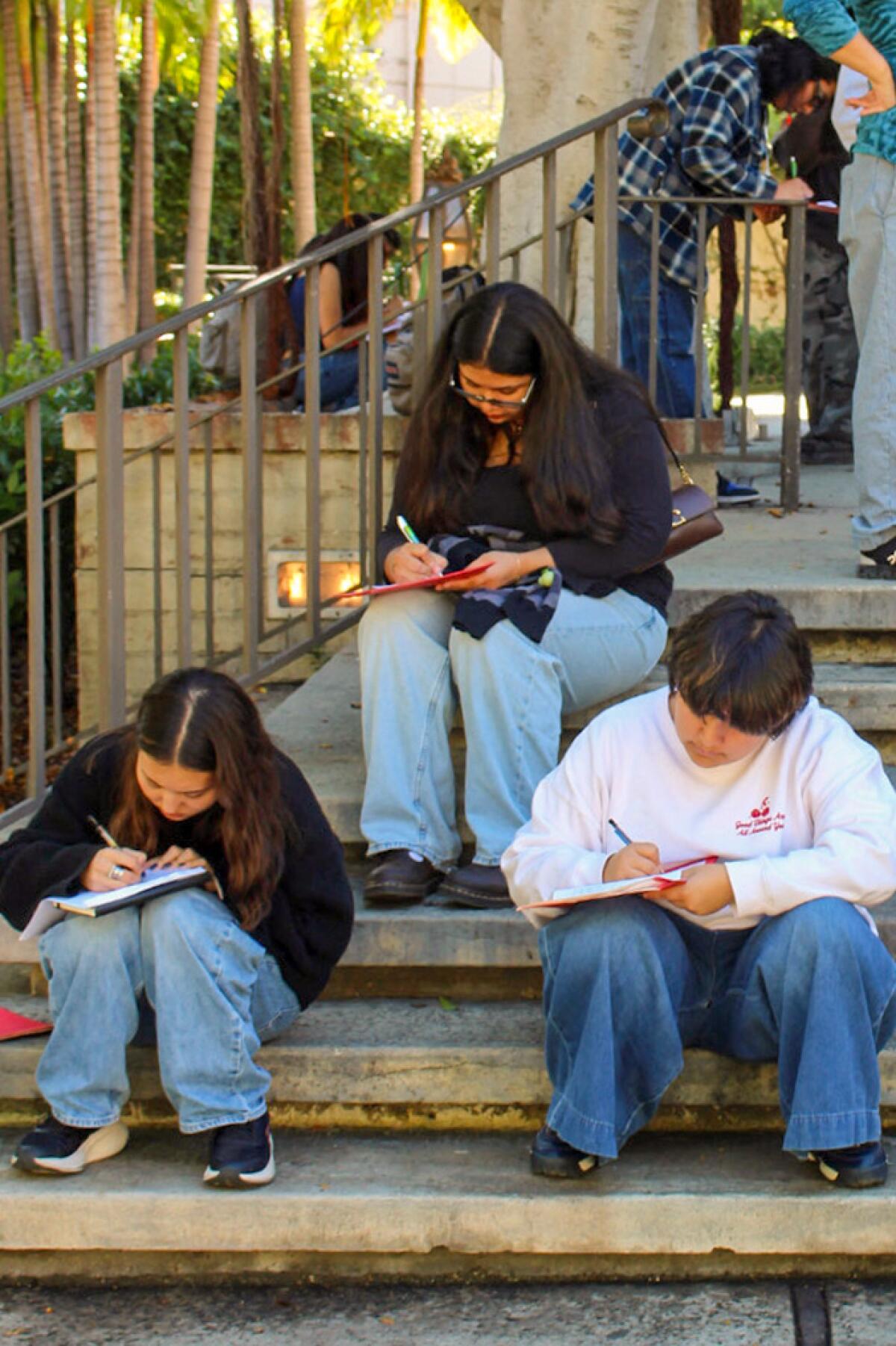

During a field trip to Gabrielino Springs and the L.A. River Gardens, Bravo High School students from Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks work on poems inspired by the landscape.

(Genesis Sierra)

TreePeople, is one of many green spaces she has visited with Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks, a program dreamed up by the West Hollywood poet laureate, Jen Cheng, in partnership with Bravo High English teacher Steve “Mr. V” Valenzuela. Cheng’s aim is for poetry, nature and Chinese principles to inspire a love for nature in students otherwise surrounded by concrete.

“I think as humans, we’re part of nature, so being better connected to nature actually brings you more home to yourself,” Cheng said. She explains that feng shui, the ancient Chinese practice of arranging a space to encourage harmony, is based on five natural elements: water, wood, fire, earth and metal.

“Feng shui, in poetry, is a lens that you can use to process big ideas using your surroundings,” Cheng said. “You can say, ‘Let’s write about water running down a river,’ not literally, but maybe as a metaphor for migration.”

Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks has grant funding through 2026’s spring semester, but next school year is still up in the air. Cheng says she’s looking for other grants, but as the Trump administration cuts humanities funding, including National Endowment for the Arts grants, the options are scarce.

As the oldest of five growing up in Oakland, Cheng felt seen for the first time when she discovered poetry in elementary school. It was inspired by her most cherished memories: field trips. At the time, her immigrant family worked to the point where they were often “too busy for nature.” During field trips, it was exciting, she said, to be out of Oakland’s urban landscape and in parks that felt rare in her working-class experience.

Decades after her elementary school field trips, as a newly appointed poet laureate for West Hollywood, she envisioned a way to mirror this childhood experience.

Poets laureate, whose role is to champion and encourage poetry in their community, are eligible for a $50,000 nationwide grant through the Academy of American Poets to support “meaningful, impactful and innovative projects,” according to the AAP.

As a recipient of this grant, Cheng brought Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks to life with one final addition — a teacher with a passion for poetry, who could connect her to a classroom of students.

Everyone she spoke to, she said, pointed her to the same person — “Mr. V.”

Jen Cheng, left, and Steve Valenzuela, right, close the Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks reading with words of encouragement for the students who shared their poetry at Bravo High School on Dec. 4, 2025. Both instructors have said that they were surprised by the emotion and creativity the students demonstrated in their poems.

(Kayte Deioma)

A sanctuary for ‘lifesaving’ creativity

When you enter Valenzuela’s classroom, the walls are covered with dozens of CD sleeves, from Deftones to Rage Against the Machine. In the gaps, student artwork, notes and photos with current and former students hang.

Valenzuela leads Bravo High’s poetry club, KEEPERS, and for the last few years, he’s guided the students to win awards at international poetry slam Get Lit.

“Poetry is expression, poetry is life-changing, lifesaving, which sounds very dramatic, but it’s not. Some of the things the students have written about are very traumatic,” Valenzuela said. “I’ve seen them work through difficult experiences and come out of it using poetry.”

One such student is 17-year-old Paige Thibodeaux. “I used to think it was better to be closed off, but throughout this, I was able to show my friends and peers who I am,” Paige said. “I didn’t think that’s something I could do and I’m here now.”

Paige, who lives with her family in Compton, recalled having her guard up as she walked through her neighborhood, where she said expression through poetry felt inaccessible.

“I don’t see a lot of kids doing things like this,” she said.

Student poets, friends and family members gather before the start of the Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks poetry reading and zine release at Bravo High School on Dec. 4, 2025.

(Kayte Deioma)

Working on a book, she said, opened up a whole new side of her. She started to confide in friends about stress, or things that bothered her, which otherwise would have stayed inside.

‘I still don’t believe it’

Since August 2025, Paige and her classmates have developed their poems, received feedback from Cheng and submitted their final pieces to be published as a poetry collection.

The cover, designed by Bravo student Adrian Lopez, depicts a tree wrapping around the spine. The poems are rooted in their observations of current affairs and native plants; the publication was completed in December, when Valenzuela and Cheng planned for a reading and celebration of their work at Bravo High.

“Did you guys know your work is going to be read across the country?” Cheng said to students in class one day. “I’m sending it all the way to New York!”

“Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks Vol. 1” is being printed as a zine and will be sent to bookstores and libraries from San Francisco to Chicago as well as the Library of Congress.

Students giggled and gasped in disbelief. “No pressure, I guess,” one student joked.

“It’s really crazy, I still don’t believe it. It’s been a dream of mine,” Alina said. “I never realized I could be a published author as a junior in high school.”

The night of the poetry reading, students, parents and friends gathered in excitement in Bravo High School’s library, settling in rows before a single microphone. Out in the hallway, the raucous chatter of teenagers echoed in the halls, and cars honked on the busy street outside to pick them up. But inside the haven of the library, there was a quiet settling among the crowd for the long-awaited show.

Alina Sadibekova reads her poems “I Want to Fly” and “Messy” for the Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks reading at Bravo High School on Dec. 4, 2025. She says writing poetry over the course of the program “grounded” her and alleviated the stress of school.

(Kayte Deioma)

Aolani “Lani” Alarcon approached the mic to hushed voices. As the lights lowered, she thanked the crowd, the white flower tucked in her hair catching the light as she recited her first poem, “White Sage.”

She says poetry didn’t always come easily to her. “One of the biggest things I struggle with is judgment, so opening up or writing about touchy subjects or things that mean something to me was hard,” Lani said. “Knowing that I wouldn’t be judged, or that people would actually like what I write, means a lot.”

The 16-year-old smiled as she read, describing sage as an ancestor’s prayer. Her next poem, “Hummingbird,” delved into grief.

“You teach me that healing isn’t forgetting,” she read, tears welling. “It’s learning to carry love without breaking under it.”

Manuel Alarcon, her father, was seated in the crowd, clasping his hands in rapt attention. When the readings had finished, he pulled Lani into a long embrace.

“These field trips, it exposed them outside of city life,” Alarcon said. “There’s more than opening a book, listening to a teacher. You need that outside exposure to really understand life. And inner city kids don’t have that. I want [my daughter] to be part of breaking a cycle.”

Valenzuela clapped loudly and cheered as each student stepped off the podium.

“When young voices, and voices from marginalized communities tend to be silenced, sometimes we internalize that and silence ourselves,” Valenzuela said. “I want them to feel like they can speak up.”

As Feng Shui Poetry in the Parks carries on for another semester— maybe its last — students continue to explore writing poetry in the greens of L.A. parks. Some, like 17-year-old Saneli Soto, express themselves along the way.

Saneli’s poem reads:

I’m used to concrete floors

And concrete walls.

I’m used to five story buildings.

I needed a quiet place.

Where I could just lie in the grass.