Stephen Cloobeck exits gubernatorial race, endorses Rep. Eric Swalwell

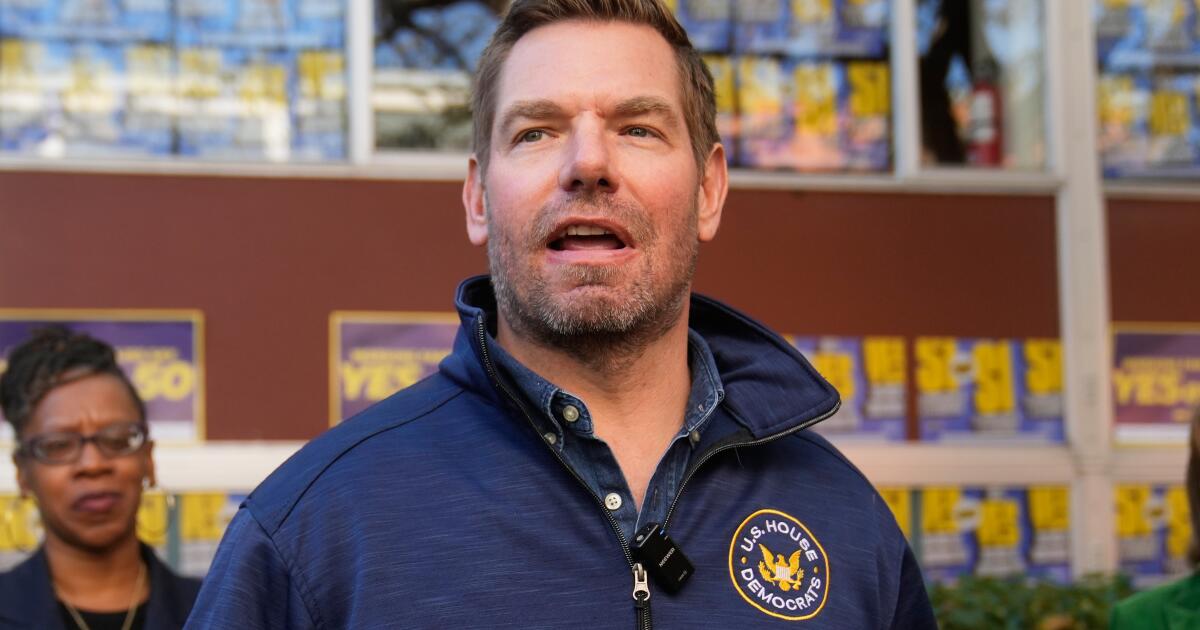

With the symbolic passing of a golden bear pin, Democratic businessman Stephen Cloobeck announced Monday evening that he was bowing out of the governor’s race and throwing his support behind noted Trump critic and close friend Rep. Eric Swalwell.

Cloobeck shared this news while appearing alongside Swallwell on CNN, saying that the San Francisco Bay Area Democrat will be the “greatest leader of this great state California.”

“I’m happy to say tonight that I’m going to merge my campaign into his and give him all the hard work that I’ve worked on,” said Cloobeck.

The announcement puts an end to the entrepreneur and philanthropist’s first-ever political campaign, which he funded through a fortune amassed in the real estate industry. In a recent UC Berkeley poll co-sponsored by The Times, Cloobeck received less than half of 1% of the support of registered voters polled.

Cloobeck said he had launched his run because he could not find a single qualified candidate — that was until Swalwell tossed his hat into the ring last week, sending an infusion of energy into the relatively sleepy race.

Pin now affixed to the lapel of his navy blue suit, Swalwell thanked his pal for the support and said he was looking forward to drawing on Cloobeck’s expertise as he worked to bring more housing and small business to the Golden State.

Swalwell, a former Republican who unsuccessfully ran for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2020, has said he is seeking the governorship to combat the threats President Trump poses to the state and to increase housing affordability and homeownership for Californians.

During his Monday evening interview, Swalwell doubled down on his proposal to implement a vote-by-phone system, despite the sharp criticism it invoked from the White House and two of his Republican challengers for governor, Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco and conservative political commentator Steve Hilton.

Swalwell said the proposal would make democracy more accessible, contending that if phones are secure enough to access finances and healthcare records, then they can be made secure enough to cast a ballot.

The backing of Cloobeck, a major Democratic donor, is good news for the congressman, who seeks to make a splash in an unusually wide open race to lead the world’s fourth-largest economy and the country’s most populous state.

About 44% of registered voters said in late October they did not have a preferred candidate for governor. The recent decisions of former Vice President Kamala Harris and Sen. Alex Padilla to opt out of the running further solidified that the state’s top job is anyone’s to win.

Times staff writer Seema Mehta contributed to this report.