Aimee Zambrano: ‘Let Us Demand a Justice System with a Gender Perspective’

Aimee Zambrano. (Venezuelanalysis)

Aimee Zambrano is a Venezuelan anthropologist, researcher, and consultant who has made significant contributions to the struggle against gender-based violence in the country. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in Women’s Studies. She is the founder of the Utopix Femicide Monitor, a platform that collects data on femicides from open sources. In this interview, Zambrano sheds light on the main challenges to advance a feminist agenda in Venezuela.

How has gender-based violence evolved in Venezuela in recent years?

It is difficult to answer precisely because there are no official figures. The former Attorney General, Tarek William Saab, presented some figures, but he did not break them down; rather, he spoke in general terms about a period during his tenure. So it is very difficult to assess what changes have occurred, especially in quantitative terms.

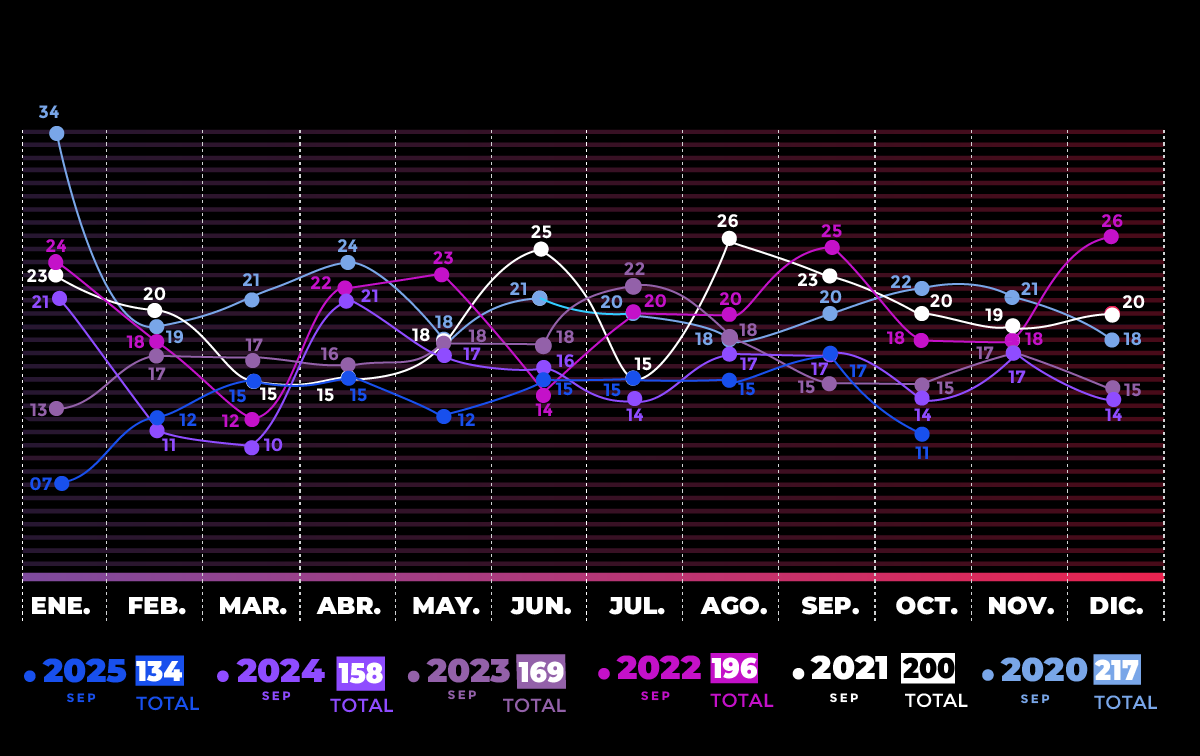

We undertake a partial registry based on cases that appear in the media, so these are not official figures. But it is enough to see patterns emerging. We have been monitoring since 2019 and saw an increase in femicides in 2020 due to the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, which also led to an increase in all types of gender-based violence, not only in Venezuela but in most countries around the world. In 2019, when we began monitoring, we recorded 167 femicides, then in 2020 we recorded 256. In 2021, there was a decrease and we counted 239 cases. In 2022 and 2023, there were 240 and 201, respectively. In 2024, we recorded 188 femicides, and for 2025, we estimate that the figure will be around 165.

There has been a decrease in the number of perpetrated femicides. However, when we look at other forms of violence, such as attempted femicides, we are seeing an increase compared to previous years. This is a warning sign because these are attempts to murder women that leave physical, psychological, and social consequences on both the survivor and her environment. We have also seen an increase in femicides of Venezuelan women abroad year after year. We are also witnessing a large number of cases of sexual abuse, especially child sexual abuse and trafficking, both abroad and in our country. Similarly, here in Venezuela, the disappearance of women is not classified as a type of gender-based violence, but according to various investigations we have carried out, disappearance or abduction, in the specific case of women, girls, and teenagers, is directly related to gender-based violence, and many of these disappearances are associated with femicides where the bodies are hidden, or cases of gender-based violence where the aggressors end up confining the victim. At the same time, we have seen a large number of cases of vicarious violence, where the aggressor inflicts violence on children, family members, or even pets.

So, a decrease in the number of femicides does not mean that other forms of violence are not on the rise. It is also important to talk about political violence. In the context of the July 2024 presidential elections, two femicides occurred and we saw threats against many community leaders by right-wing groups, who persecuted and harassed them. The same goes for media violence, social media, and artificial intelligence. In fact, there need to be changes in the laws so that these new forms of violence can be punished.

How does the lack of official and updated figures from the Venezuelan government affect the implementation of effective public policies to combat gender-based violence?

It has a huge impact. It’s not that there are no figures, but that they are not public. In fact, several public programs such as the Mamá Rosa Plan for Gender Equality and Equity, the various homeland plans, and even the Organic Law on Women’s Right to a Life Free of Violence, mandate that the state must create an observatory for gender-based violence.

The absence of data means that we cannot measure the efficacy of the public policies that are being enacted. Statistics could also allow organizations to develop proposals, not only legislative ones, but also from women’s groups, which must also participate in the elaboration of these policies.

It is often said that the deterioration of living conditions in Venezuela disproportionately affects women, but what does this mean in practice? Does it also impact the number of femicides?

Yes. We were affected by the rentier culture, the crisis, and economic sanctions. It has been a multifactorial phenomenon. The rentier culture did not change, public policies depended on oil revenues, and a series of US-led unilateral coercive measures were imposed on us that affected all aspects of life. In crises, it is always women’s bodies that pay the price. Currently, we have to work four or five jobs, usually informal ones, to make ends meet. For those of us with children, it is even worse, because we also have the burden of unpaid work in the home. The same is true for the care of the elderly or people with disabilities, which always falls on our shoulders.

In Venezuela, the vast majority of heads of households are women, who are either alone or part of extended families of women living together and raising children. In addition to this, women are the ones who make up a large part of the social fabric, they are grassroots leaders. At the same time, the country is experiencing a crisis in services, electricity, water, and gas, which further increases the burden of care work. Women have to figure out how to get water for cooking, washing, and bathing their children, how to cope when there is no electricity, or how to cook without gas, especially in the interior of the country, where public services are in a more dire state.

Does this have an impact on the number of femicides? It does. Violent, aggressive men find themselves in the midst of an economic crisis, where there is unemployment or underpaid work, they become increasingly frustrated, and where do they take out all this frustration? On women, their partners, their families, their homes. It would be interesting to see if GDP figures or periods of high inflation correlate with peaks in femicides.

With the US attacks on January 3, we saw the kidnapping of Cilia Flores and also the rise to power of the first female president, albeit in an acting capacity, Delcy Rodríguez. How can this be interpreted from a feminist perspective?

The bombing of Venezuela was a flagrant violation of international law, but we also saw how National Assembly Deputy Cilia Flores appeared during the arraignment hearing in New York with bruises on her face and body. Her attorney requested medical attention, which indicates that during the operation she was the victim of violence by the US military. This, of course, is indicative of what foreign powers do when they bomb and invade other countries, especially in the Global South, where they do so to extract natural resources.

Talking with friends, I have realized that many of us feel violated, as women, by everything that has happened. Now the acting president, Delcy Rodríguez, has a very difficult task: to take the reins of the state with a gun to her head. It takes a lot of courage to face this. In addition, after the bombing, Trump’s threat to her was very direct: do what I want or you will be worse off than Maduro. It is difficult to take on that role and have the responsibility of preventing more lives from being lost.

In the current context, what are Venezuela’s main challenges in terms of the feminist agenda? You have suggested, for example, the need to create a structural feminist emergency plan. What would that look like?

The first thing is to define what that feminist agenda is, because in Venezuela there are different grassroots movements and organizations with different political stances, and polarization sometimes makes it very difficult to unify the points. Sometimes we try, but the efforts can get fragmented again due to specific political events. I would say that there is the issue of gender violence and also the decriminalization of abortion in Venezuela, as common ground that unifies many of us. We also demand a justice system that has a gender and feminist perspective because the current one is built from an androcentric, patriarchal perspective; that is, it is a justice system created by men and for men. An amnesty law is currently being implemented, so this has to be included in it.

By a feminist emergency structural plan, we mean that the Ministry for Women and Gender Equality should not be the only institution responsible for public policies relating to women and the LGBTIQ+ population. It should rather involve the entire state. I am not saying anything new because this already appears in the Organic Law on Women’s Right to a Life Free of Violence and also in the Mamá Rosa plan, which was supposed to culminate in 2019, but almost nothing that was stipulated ended up being implemented. All ministries, all affiliated entities, all state institutions, including governors’ and mayors’ offices, must address gender issues, and a robust budget is needed for this. For example, the Ministry of Communication must run ongoing campaigns in the media and on social networks about the different forms of violence and the telephone hotlines and websites where incidents can be reported. The Ministry of Housing must focus on creating shelters for victims. The Ministry of Education must review the curriculum to include gender studies, comprehensive sexuality education, and different types of violence, as well as implement protocols for care in schools, high schools, and universities. In addition, all state officials have a duty to educate themselves on the issue.

How do you assess the retreat of the state in certain areas and the growing “NGOization” leveraged by Western funding?

It’s complex because initiatives, activities, marches, etc., require resources, and many of our organizations don’t have them. In addition, there is another factor at play here, which is the proliferation of religious groups, especially Pentecostal evangelicals, who have grown significantly in Venezuela, have a presence within the state and within political parties, and are also very wealthy, which allows them to carry out campaigns, mobilizations, etc. Feminist movements face many obstacles because most of us also have to work several jobs and take care of our homes and communities. So it is difficult to keep up with evangelical and conservative right-wing groups.

I think we need to identify who the enemies are, who targets our rights, and then assess the contradictions and coordinate women’s and feminist movements. I make the distinction because there are women’s organizations that do not necessarily identify as feminist. But we have to grow, see what issues unite us, and begin a series of actions. I always make this call: despite our political differences, let’s try to unite around an agenda that unites us all.

How does social media influence the proliferation of violence, and gender violence in particular?

I believe that violence has always been present, but now it is exposed because some forms of violence that we used to consider normal or common have been explained or denormalized. In addition, social media and the internet allow us all to learn about different cases in different parts of the world. But, on the other hand, we have the issue of anonymity and lack of accountability, meaning that people can say outrageous things, threaten, insult, and commit violence facilitated by technology. Social media also allows virtual groups to come together to commit violence, and there are also certain influencers on Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok spreading crazy ideas. Guys like El Temach in Mexico, who speak to you from their machismo, what some call “toxic masculinity” but I call “the healthy descendant of patriarchy.”

There is also another point here: the algorithm. For example, a teenager starts searching for content about exercise, and soon after, the algorithm will introduce them to these influencers, thus creating mass communities such as incels, which organize themselves through forums like Reddit. This also breaks down the entire social fabric of face-to-face interactions, and people end up isolated but believing they are “accompanied on social media.” All of this leads to disorders such as anxiety and depression. In addition, teenage girls and women become caught up in the aspirational idea of having a certain type of body, aesthetic violence, etc. In short, I’m not saying this from a moralistic point of view, but social networks have encouraged a lot of violence. Besides, who owns these networks? What ideology do they profess? What are they using them for? We have to investigate so we can arm ourselves and fight this battle.