3 L.A. hiking trails that offer opportunities for quiet reflection

I didn’t mean to ruin anyone’s new year cheer, but I also didn’t expect so many people around me to be on news cleanses in 2026.

I was visiting a friend in a mental health facility in early January when he told me news I didn’t believe: that the U.S. had captured the Venezuelan president. I asked him how he knew. A staffer had told him. I did not believe him. Sounds like AI-generated misinformation, I thought to myself.

After leaving, I called my friend, Patrick, who listens to so many podcasts, I’ve wondered if he plays them as he sleeps just to stay informed. “Can you believe the news?” I said without saying hello. He didn’t know what I was talking about.

“I’ve been taking a news cleanse with the new year,” he said. “What’s going on?”

I proceeded to tell three more people about the raid on Nicolás Maduro’s compound, including a friend on a camping trip who was probably much happier before she read my text.

And that was just Day 3 of 2026. Over the past month, Americans have faced overwhelming, heartbreaking and frightening news. I cannot be the only one who sometimes closes my eyes when I open a news app, doing a quick countdown before I read the headlines.

It’s even more important in these challenging times to take moments in the day for quiet reflection. Meditation, which can include prayer, has a tremendous number of health benefits, including lowering stress and anxiety and helping us be less reactive or quick to anger.

Below you’ll find three hikes with places along their paths where you can easily sit or lie down. If meditation isn’t your thing, consider practicing mindfulness. You could take a moment to play what I call the “color game,” where you try to spot something from each color of the rainbow (including indigo and violet, if you’re feeling lucky). I’m always amazed at how much color I can spot even just on a walk in my neighborhood.

I hope you find a moment, at least, of peace as you explore these trails.

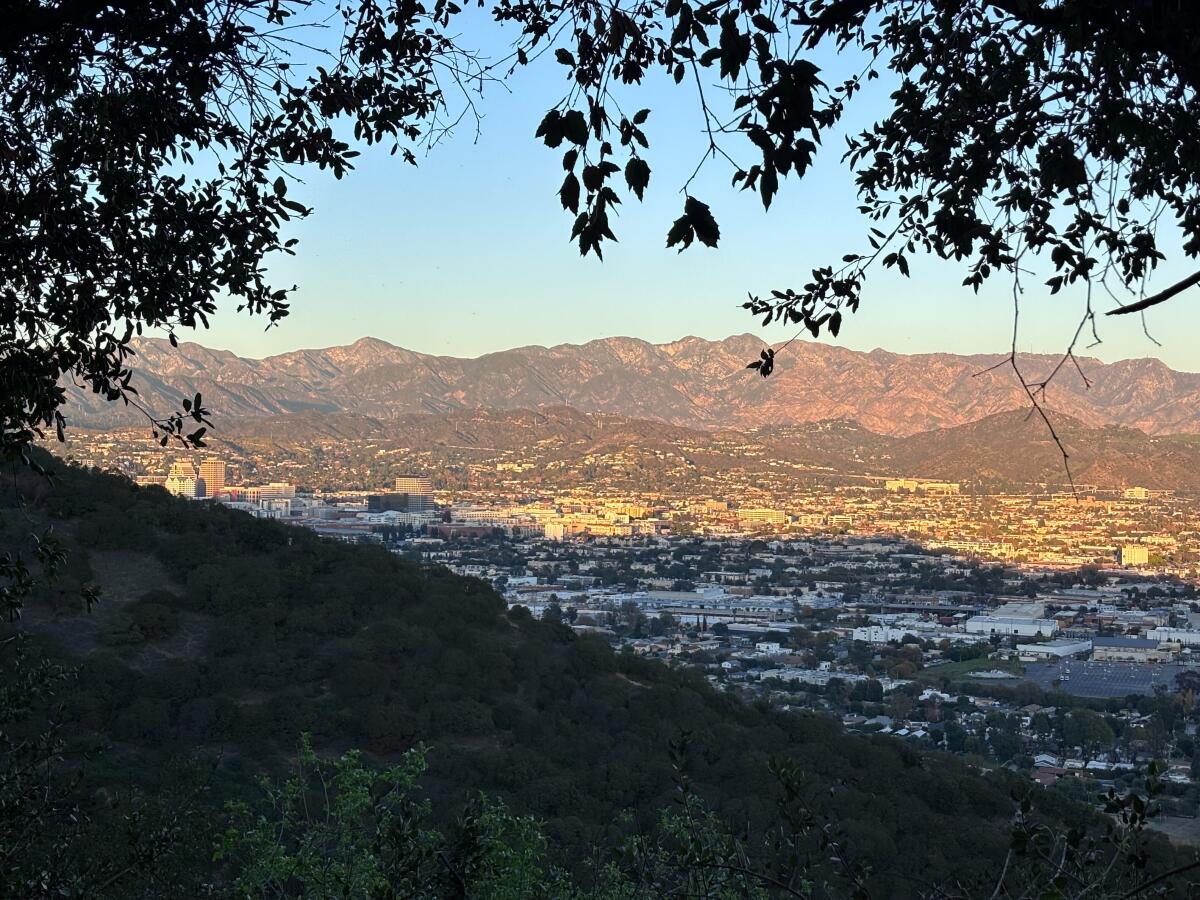

The Verdugo and San Gabriel mountains, as seen from a trail to 5-Points in Griffith Park.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

1. 5-Points/Beacon Hill Loop (Griffith Park Explorer Segment 11)

Distance: 6 miles

Elevation gained: About 1,200 feet

Difficulty: Moderate

Dogs allowed? Yes

Accessible alternative: Los Angeles River Bike Path from North Atwater Park

The 5-Points/Beacon Hill Loop is a six-mile excursion through the southeast corner of Griffith Park that offers epic views of L.A. and its neighboring cities.

To start your hike, you’ll park near the Griffith Park Merry-Go-Round and head south to the trailhead. You’ll take the Lower Beacon Trail east and head uphill and soon be able to spot the L.A. River and the cable-stayed, 325-foot North Atwater Bridge.

You will follow the trail as it curves and runs parallel to Griffith Park Road before meeting up with the Coolidge Trail just over a mile in. The Coolidge Trail will take you west and then north toward 5-Points at 2.3 miles into your hike. (Note: The Griffith Park Explorer version of this route includes short in-and-back jaunts that I’m not including here, so my mile markers will be different.)

The 5-Points trail is aptly named, as it’s a location where five trails converge. I’d recommend taking the 1/5-of-a-mile Upper Beacon Trail, which takes you northeast up to Beacon Hill. It’s briefly steep but is worth it for the great views of downtown L.A. and the surrounding area. And it is a great spot for you to take a moment for meditation or mindfulness.

From Beacon Hill, you can head back to 5-Points and continue southwest to the Vista Viewpoint, a lookout point that’s usually more crowded but still stunning. Or take the Fern Canyon Trail to loop back to where you parked. Or both!

As an extra treat: This weekend is the full moon. On Sunday, you can take this hike to 5-Points, a great spot to watch the moon rise. I once crested a hill at 5-Points only to witness the Strawberry Moon, June’s full moon, rise over the Elysian Valley. My friends and I cheered over our luck.

The moon is expected to rise at 5:24 p.m. Sunday. I hope you catch it from this epic lookout spot. (And yes, it’s another place to pause in quiet reflection, taking in the beauty of our Earth.)

The Musch Trail, or Backbone Trail, takes hikers through lush meadows.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

2. Backbone Trail to Musch Trail Camp

Distance: 2 miles out and back (with option to extend)

Elevation gained: About 200 feet

Difficulty: Easier end of moderate

Dogs allowed? No

Accessible alternative: Sycamore Canyon Road

This two-mile, out-and-back jaunt through Topanga State Park takes you through lush meadows and chaparral where you’ll likely spot wildflowers and wildlife.

To begin your hike, you’ll park at Trippet Ranch and pay to park before heading out. The Musch Trail is in the northeast corner of the lot. You’ll take the paved path just 1/10 of a mile before turning on the dirt path, the Backbone Trail.

The Musch Trail Camp in the Santa Monica Mountains.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

The ranch was originally called Rancho Las Lomas Celestiales by its owner Cora Larimore Trippet, which translates to “Ranch of Heavenly Hills.” You’ll find, as you hike through those hills covered in oak trees, black sage, ceanothus and more, that the name still rings true today.

A mile in, you’ll arrive at Musch Trail Camp, a small campground with picnic tables and log benches. As you pause, listen to the songs of the birds. California quail, Anna’s hummingbird and yellow-rumped warbler are commonly spotted. Stay quiet enough, and you might just spot a mule deer, desert cottontail or gray fox.

From the trail camp, you can either turn around or continue northeast to Eagle Rock, which will provide panoramic views of the park. From Eagle Rock, many hikers take Eagle Springs Fire Road to turn this trek into a loop. Regardless of which path you take, please make sure to download a map beforehand.

Boulders at Mt. Hillyer in the San Gabriel Mountains.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

3. Mt. Hillyer via Silver Moccasin Trail

Distance: 5.8-mile lollipop loop

Elevation gained: About 1,100 feet

Difficulty: Moderate

Dogs allowed? Yes

Accessible alternative: Paved paths through Chilao Campground

This six-mile jaunt along the Silver Moccasin Trail, which is just over 50 miles when fully open, takes you through high desert and pine trees.

Shaped like a lollipop, the trailhead sits about half a mile northwest of the Chilao Visitor Center, which is typically open on the weekend. You will head north for a mile before turning left off the Silver Moccasin Trail.

You will follow Horse Flats Road to Rosenita Saddle, where you’ll take the trail southwest to Mt. Hillyer.

Keep an eye out for Jeffrey pines, which will have deeply furrowed bark and round prickly cones. Their bark smells like butterscotch or vanilla, which I always love pausing to sniff.

A hiker takes the path to Mount Hillyer in Angeles National Forest.

(Jaclyn Cosgrove / Los Angeles Times)

The trail also features Coulter pines that produce massive cones nicknamed widowmakers because of their size. The Coulter pine cones can weigh up to 11 pounds. If you’re in the area when it’s windy, please watch your head.

To reach Mt. Hillyer, you’ll follow a short spur trail about half a mile southwest from the Rosenita Saddle. Mt. Hillyer features several large boulders, perfect for stopping to meditate. It’ll also offer you sweeping views of the San Gabriel Mountains.

You can make the trail a loop by continuing south until it jags back east, meeting back up the paved road you previously took.

Outside of rock climbers, this trail isn’t terribly popular, so you’ll likely have opportunities along the way to pause.

Deep breaths. We’ll get through this together!

3 things to do

Participants prepare for the Griffith Park Run during a previous year’s event.

(Los Angeles Parks Foundation)

1. Hit the hills in L.A.

There’s still time to register for the Griffith Park Run, a half marathon and 5K through L.A.’s iconic park on Sunday. Participants will start the half marathon at 7:30 a.m. and the 5K at 10 a.m. This is the first year dogs are allowed to run alongside their owners in the 5K. Proceeds benefit the Los Angeles Parks Foundation. Register by 11:59 p.m. Saturday at rungpr.com.

2. Learn to ride a bike in El Monte

ActiveSGV, a climate justice nonprofit in San Gabriel Valley, will host a free class from 9:30 to 11:30 a.m. Sunday about how to ride a bicycle. Students will be taught about balancing atop a bike, along with tips on starting, stopping and controlling the bike. The class is open to all ages, including adults. Preregistration is required. Register at eventbrite.com.

3. Welcome the upcoming full moon near Chinatown

Clockshop, an arts and culture nonprofit, will host “Listening by Moonrise,” from 3 to 5 p.m. Sunday at Los Angeles State Historic Park. A seasonal series held around the eve of a full moon, the event will feature performances and immersive sound experiences. Learn more at clockshop.org.

The must-read

Last summer, nature enthusiasts hiked a steep trail to see California poppies growing near the community of Elizabeth Lake.

(Raul Roa / Los Angeles Times)

Outside of Friday’s lottery numbers, few things draw more speculation than whether Southern California will experience a superbloom. Recent hot weather in January threatened our chances, Times plant queen Jeanette Marantos wrote, but that doesn’t mean all hope is lost. Wildflower expert Naomi Fraga told Marantos that more rain and lower temps would help, but even still, superblooms remain tricky to predict. That said, there will undoubtedly be flowers this spring! “We had lots of rain, so no matter what, I’m excited for the spring, because it’s a great time to enjoy the outdoors and see an incredible display by nature,” Fraga said.

Happy adventuring,

P.S.

Officials at Angeles National Forest are seeking public feedback on what, if any, changes they should make in how they manage the Mt. Baldy area of the forest. In light of recent deaths and rescues in the area, there has been increased pressure from local officials to implement a permitting process to hike in the area. You have until Feb. 28 to submit comments.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.