Palestinians in Gaza say ‘Board of Peace’ will further occupation | Gaza

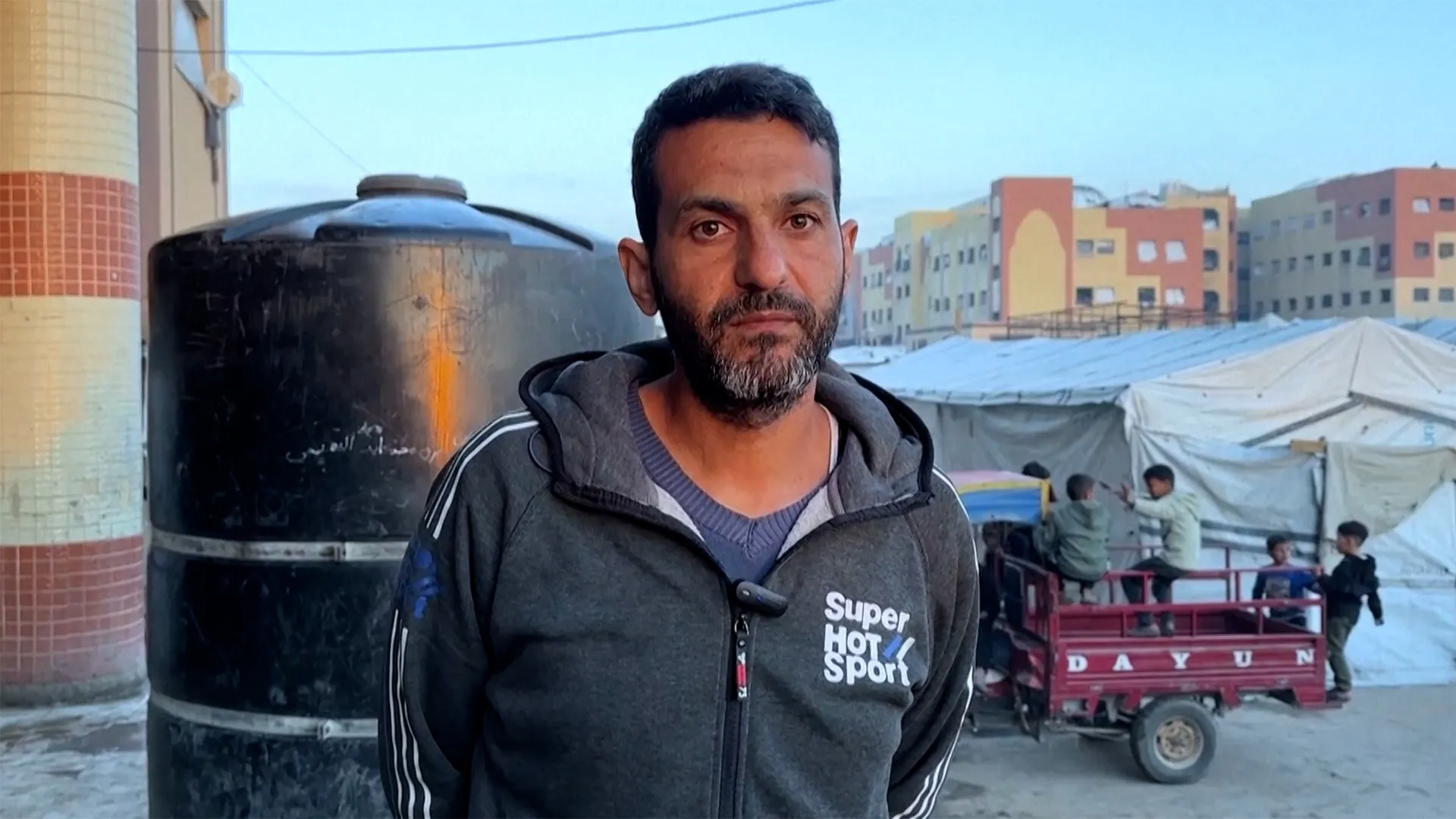

“Another gateway to the occupation of Palestine.” Many Palestinians in Gaza reacted to the inaugural meeting of Donald Trump’s so-called “Board of Peace” with deep scepticism, seeing it as a way to further Israel’s illegal occupation of the territory.

Published On 19 Feb 2026