Nigerian Women’s Struggle Against Sexual Coercion

“I have mental fortitude, I am physically stronger, but I cannot undo what was done to me. Why do they do things like this and get away with it?” Aria John’s* voice cracked from the weight of her grief, the realisation that justice was not attainable, and the knowledge that her struggles were seen as disposable.

Aria’s first sexual experience was at 16, when she became involved with a 23-year-old. In Nigeria, sexual relations between a minor and an adult are regarded as statutory rape according to the Child’s Rights Act. Still, it would be many years before she could name what happened.

She first met him at a party. That night, he tried to make physical contact with her repeatedly without her consent. She found it uncomfortable, but did not understand the gravity of his actions at the time.

It was a case of sexual coercion, where someone is pressured or manipulated into a sexual activity against their freely given consent. Such experiences can take many forms, including violence, persistent insistence, verbal threats, and emotional manipulation, among others, which can manifest in the form of verbal sexual abuse, forceful penetration, threats of abandonment, withholding support, transactional sex, and other economic incentives. These acts violate fundamental human rights and can negatively impact an individual’s social, reproductive, mental, and economic well-being. Children and young women are the biggest victims of sexual coercion in Nigeria.

Two days later, the man invited Aria to his house, and she accepted. The visit culminated in rape; she was in pain throughout, and she asked him to stop, but he did not.

“Afterwards, he asked me if I was sure I was a virgin because I did not bleed,” she recalls.

During their time together, his friends also became her friends. When he started to push her away, it left her isolated, adding to the trauma she experienced as a result of the sexual abuse.

Halima Mason, a psychologist and sex and relationship therapist, describes coercion as a form of sexual violence that exists on a spectrum.

“It occurs when a person is pressured, manipulated, intimidated, or emotionally worn down into sexual activity they do not freely want. It often happens without physical force, which is part of why it is so frequently minimised or misunderstood. Many survivors describe agreeing to sex even when they did not want it, driven by fear of the consequences, exhaustion from ongoing pressure, or a sense that resistance was too costly or dangerous,” she explained.

A study in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria, shows a prevalence rate of 59.1 per cent of sexual coercion against female school students. It also highlighted the high rates of paedophilia, especially affecting primary school students, leaving them vulnerable to both teachers and fellow students.

“When consent is shaped by fear, pressure, or obligation, genuine choice is absent,” Halima told HumAngle.

“Within long term relationships and marriages, sexual coercion can become especially entrenched. Cultural expectations around commitment, duty, and endurance often make refusal feel unacceptable. Pressure may be framed as normal relationship maintenance, compromise, or marital responsibility. Partners may imply that sex is owed, accuse the other person of withholding, or suggest infidelity or abandonment as consequences of refusal,” she added.

At the time, Aria said she did not consider “pursuing justice because even people who were raped with evidence are not believed”. “This is not my first experience,” she lamented. “How many men do I want to take revenge against? When things hurt you, you grow around your pain; it’s not crippling, but it’s still very painful. It hurts so much. If you speak out, they will call you an ashewo and say you must have wanted it.”

Aria started going to the gym and running to become physically stronger and avoid situations where people force her to do things she doesn’t want to do.

She expressed the belief that things might have been different for her if she had received sufficient love growing up, which would have discouraged her from seeking it elsewhere.

“If your daughters know love, they will not look for it in places where there isn’t any, because they know what love looks like. I still find myself in similar situations even when I know it’s illogical,” she told HumAngle.

Another experience started one evening during a conversation with her neighbour. He asked her out, and she turned him down. Aria also told him that she was celibate at the time, and if anything was to happen between them, it wouldn’t lead to sex. He became infuriated.

“He was furious, leaving me shocked, especially when he said it’s probably because I was sexually abused in the past, and that’s why I did not want to sleep with him. I never explicitly told him that,” she recounted.

This guilt-tripping is a tactic often used by predators to get the victim to lower their guard and give in, in an attempt to defend themselves or prove something. She said she saw through this manipulation and refused to give in to his tantrum.

Aria has suppressed her memories over the years because they feel suffocating, and her childhood experience with bullying led her to become obsessed with being perceived as strong, causing her to close off.

“I don’t let myself get vulnerable because people can hurt me, and I don’t have any defences,” she said.

Halima pointed out that life experiences also shape vulnerability, as children who grow up with emotional neglect, inconsistent caregiving, or conditional affection may develop patterns that influence how they understand love and safety.

“When care was unpredictable, some people learned to earn closeness through compliance and self-silencing. As adults, they may prioritise others’ needs over their own discomfort, struggle to recognise safe relationships, or tolerate pressure to please. These patterns do not cause coercion. Responsibility always lies with the person who chooses to exploit, pressure, or manipulate. Early relational wounds can, however, make it harder to recognise coercion early and to act on internal warning signals,” she explained.

This mirrors Aria’s experience as she explained how the experiences shaped her relationships: “I struggle to keep friends and get close to people, making me emotionally unavailable. I don’t have long-term relationships. Even when men treat me well, I just keep them at arm’s length,” she told HumAngle.

A social issue

The social manifestations of sexual coercion come in ways other than what Aria experienced. In addition to being the subject of gossip, some women experience pressure from society to succumb to romantic or sexual advances.

Oye Peter’s* story started in a place she considered a sanctuary. As a devout Anglican, she regularly attended church services. Even though she was in her early twenties, she knew exactly the kind of man she wanted to date, and Joseph* did not fit the picture. The people around her believed otherwise.

She met him during a Youth Convention in 2023. He first approached her through other youth leaders. She politely told them she was not interested in pursuing a relationship with him. Joseph was a respected youth leader, and there was a natural expectation of trust in him, which made it easier for him to gain access to her life.

“I was in my final year then, preparing for my project and everything. But they kept reaching out to me even after I graduated. Most times, I don’t even respond to his messages,” she said.

Oye had a good relationship with her church leaders, and they tried many times to convince her to give him a chance as he is ‘a good person’. His influence on their mutual acquaintances created subtle pressure and made his behaviour seem normal and acceptable. The age gap did not seem to raise any concern for them, even though she was only 23 and he was around 35.

During her National Youth Service in Onitsha, Anambra State, southeastern Nigeria, she was invited to a church programme in nearby Asaba, Delta State. She expected, due to past experience, that accommodation would be provided. However, when she arrived, she was told there was only one room available to share with Joseph. She was uncomfortable but confident that nothing could happen between them.

However, he started to make sexual advances towards her during the night, but she refused to give in.

“I felt bad, used, and manipulated. Later on, I reached out to one of the youth leaders to express my concern, and not long after, I discovered that the man was even married. I was so angry that some of the youth leaders who knew he was married were trying to use their influence to force me into a relationship with him,” she recounted.

They insisted they meant well and that he would take care of her if she agreed to be with him. When Oye pointed out his marriage, one of her diocesan youth leaders laughed and dismissed it as ‘something men do’, which made her feel invalidated and unsupported. They also blamed her for ‘not being respectful’ to him when she turned him down.

Even though Oye was grateful nothing happened between them, the manipulation tactics used and the lack of desire to hold him accountable for his actions caused her to withdraw from the youth activities because she no longer felt safe or respected.

“I wish people understood that discomfort is enough; if someone feels uneasy or pressured, that means that consent is not present. No one should assume they know what another person wants. I did not pursue formal justice; I blocked him and everyone associated with him. The dismissal I experienced the first time I spoke up discouraged me,” she lamented.

Halima, the psychologist, said that the impact of sexual coercion on survivors is deep and far-reaching, as many experience anxiety, depressed mood, shame, dissociation, trauma symptoms, and confusion about what happened, particularly when there was no overt violence.

“When coercion comes from a trusted partner, leader, or authority figure, it creates a specific kind of trauma rooted in betrayal, which can damage self-trust and make it difficult to rely on one’s own perceptions,” she explained.

Oye believes that the fear of judgment, victim-blaming, and the belief that some men cannot engage in this type of coercion keep many survivors worrying that they will not be believed. She believed that a fair hearing, genuine validation, and people taking her discomfort seriously would have helped her feel better.

“I later confided in a friend who is a psychologist. Her support was very helpful and validating,” she said.

Within the lines of matrimony

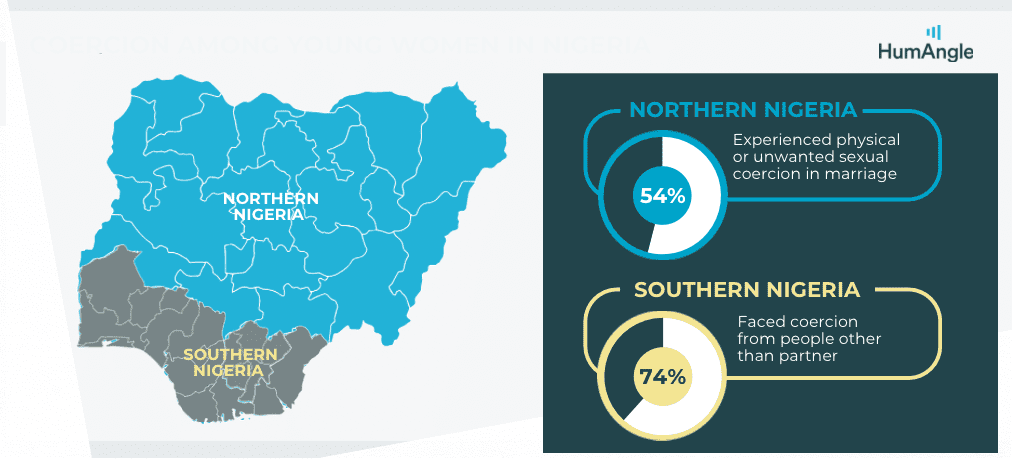

A Nigerian study of 12,626 women aged 15 to 24, from the six geopolitical zones, shows that spousal coercion is more common in the northern part of the country, with 54 per cent of respondents reporting physical or unwanted sexual coercion in their marriages, while non-spousal coercion is more prevalent in the south, with 74 per cent of respondents reporting experiences of coercion from people other than their partners.

Halima says sociocultural and religious beliefs shape this form of violation, sometimes leading to laws that protect perpetrators.

“In Nigeria, these dynamics are intensified by strong social and religious narratives that prioritise marital stability and female submission. Many women are socialised to believe that endurance is part of being a good wife and that sexual access is a husband’s right.

“Religious texts and teachings are sometimes selectively interpreted or weaponised to justify coercion, with scripture used to reinforce submission rather than mutual respect and care. When women seek help from religious leaders, they may be counselled to endure or submit rather than being supported in setting boundaries or leaving harmful situations,” she explained.

Even in professional environments

Sexual coercion also happens in professional settings. Nafisa Isiaka’s* experience took place during a teaching job at a private Islamic school in North Central Nigeria in 2021.

“I could sense from the beginning that he probably wanted more than an employer-employee relationship,” she said of the man who interviewed her for the job.

“He kept saying things like, you are very pretty, you are so smart, and so on. I did not trust him, especially after he once tried to hug me without consent,” she recalled.

Nafisa is a Muslim woman who stays away from skinship with non-related men, so this was a major violation for her, but since she needed the job, she tried to put it behind her.

She felt uncomfortable with his stares, leading her to finally open up to her mother, holding back some parts because she knew her mother would encourage her to leave the job, and she couldn’t afford to at the time due to her financial situation and her desperation to leave her old job.

“I thought that since he wasn’t my direct employer, I should be fine, but he would text me outside of work hours, and come to my class during work hours. He talked to me in suggestive ways and probably about me as if we had a closer relationship than simply employer and employee. A colleague later confessed that she had honestly thought something was going on between us,” Nafisa recalled.

One time, he said they weren’t children and that she shouldn’t pretend not to know what he meant. Once, when she complained to a colleague, she simply said, “Yes, he can be like that sometimes.”

The man also implied that she was ‘prudish’ multiple times, and often came close to her and tried to touch her. He was very tall, and she believed he would close in to intimidate her. Over time, he started picking on her and often criticised the way she did her job. She sometimes talked back to him.

“I am not sure if it was the right thing to do at that time, but he irritated me so much. I would lean back when he leaned too close and make it obvious I was avoiding him. After the school break, I got wind of the fact that they were planning to sack me because they were carrying out a revamp, and they eventually did,” she recalled.

But that did not make him leave her alone. After she left, he continued trying to establish contact.

When the student feels unsafe

Sexual coercion in professional relationships happens in many layers, often leaving the victim carrying the weight of the damage in their lives. Murjanatu Habeeb’s* experiences were punctuated by her own questions, wondering if what happened to her was really as violating as it seemed.

Her experience, which began in 2024, was so subtle that it took her a long time to recognise it for what it was. The man was a lecturer at her university. As the class representative, she had her lecturers’ contact information, including his, to better manage her tasks of coordinating her classmates and obtaining appropriate information about schedule changes. She estimates that he was in his 30s.

At the end of that session, the then 19-year-old, in need of guidance, reached out to him to ask for help with her curriculum vitae. That was when he started to make her uncomfortable.

“Initially, I pretended not to understand the hints he was dropping… It got to a point when he just started to get more direct.”

Due to a flood that happened in Maiduguri, northeastern Nigeria, where she was based at the time, she couldn’t resume school on time and had to go to her lecturers’ offices to explain her absence.

“I started getting help from him, but he started to ask me to meet him outside school. I declined and told him I was only in contact with him to establish a professional relationship, but he kept pushing. I even told him I was in a relationship,” Murjanatu recounted. He also made inappropriate compliments about her looks.

One day, in the middle of a conversation, she mentioned in passing the area where she lived. Days later, he sent her a message saying he was in her area and was probably ‘even close to her home’, she recalled.

“He said he thought we should greet and asked if I could come out. I naively went to meet him; he was in a car, and I refused to get in at first, but he managed to convince me to. While I was in the car, he kept insisting that we hold hands. I refused. Looking back now, I am so glad that I did not fall for it, but it felt very uncomfortable,” she says.

The power imbalance between them worsened the situation. After this encounter, he became hostile towards her. Once, during rehearsals for an event at school, Murjanatu took off her veil because of a headache from the tight plaiting of her hair. The lecturer, who was present at the rehearsal, became upset.

“He started to lecture me on the inappropriateness of opening my hair. He started attacking me over random things that did not have much to do with him. When I woke up the next day, I messaged him and expressed how I felt about the situation… I told him to be careful and wary of me,” she recounted. Murjanatu felt she could have set better boundaries earlier, but she did not take his advances seriously at first.

He stopped for a while, but in her third year, during her Student Industrial Work Experience Scheme (SIWES), where she did so well that she was recognised by the organisation she was attached to, he was one of the lecturers at her defence. He downgraded her. When she confronted him, he claimed her slides were inaccurate.

“That was the first time I felt like I was deprived of something I knew I deserved,” she said. “The second time was during our test in the last semester, when we asked him for an extra five minutes, which he granted. But before time was up, he came to my seat and demanded that I submit my paper, even though everyone else had received the same extension. He insisted that if he skipped my seat, he would not collect my paper. I gave up and submitted.”

The hostility persisted until she finally confided in her mother, who immediately suggested that she change her supervisor. She believes that her mother being an anti-gender-based violence advocate made it easier for her to understand her perspective.

“She said his reaction was unprofessional, and when I opened up to my therapist, she also insisted that I change him as a supervisor. I don’t know what to say to access any formal support, because he did not harm me physically, and I don’t know how to explain it,” she added.

She reported to the Head of Department (HOD) and said she wanted her supervisor changed, explaining the situation, but not giving too many details. He requested evidence, and she informed him that, although she used to keep a record of the chats, she had lost them after changing her phone. She added that a friend could corroborate her story. The HOD made her feel listened to, and she is currently following up on that, hoping the much-needed change comes through.

“I felt like if I did not get support from my mother, therapist, and partner, it would have destroyed me,” the now 21-year-old said.

Halima says that the benefits of trauma-informed sharing of the stories of victims help shift the focus from self-blame to accountability.

“While the impacts of sexual coercion are profound, healing is possible. With proper therapeutic support, safe relationships, and a community that believes and validates survivors’ experiences, many people are able to rebuild trust in themselves and others, reclaim their sense of agency, and experience intimacy that is genuinely mutual and free,” she said.

*Names marked with an asterisk are pseudonyms used to protect the identities of the sources.