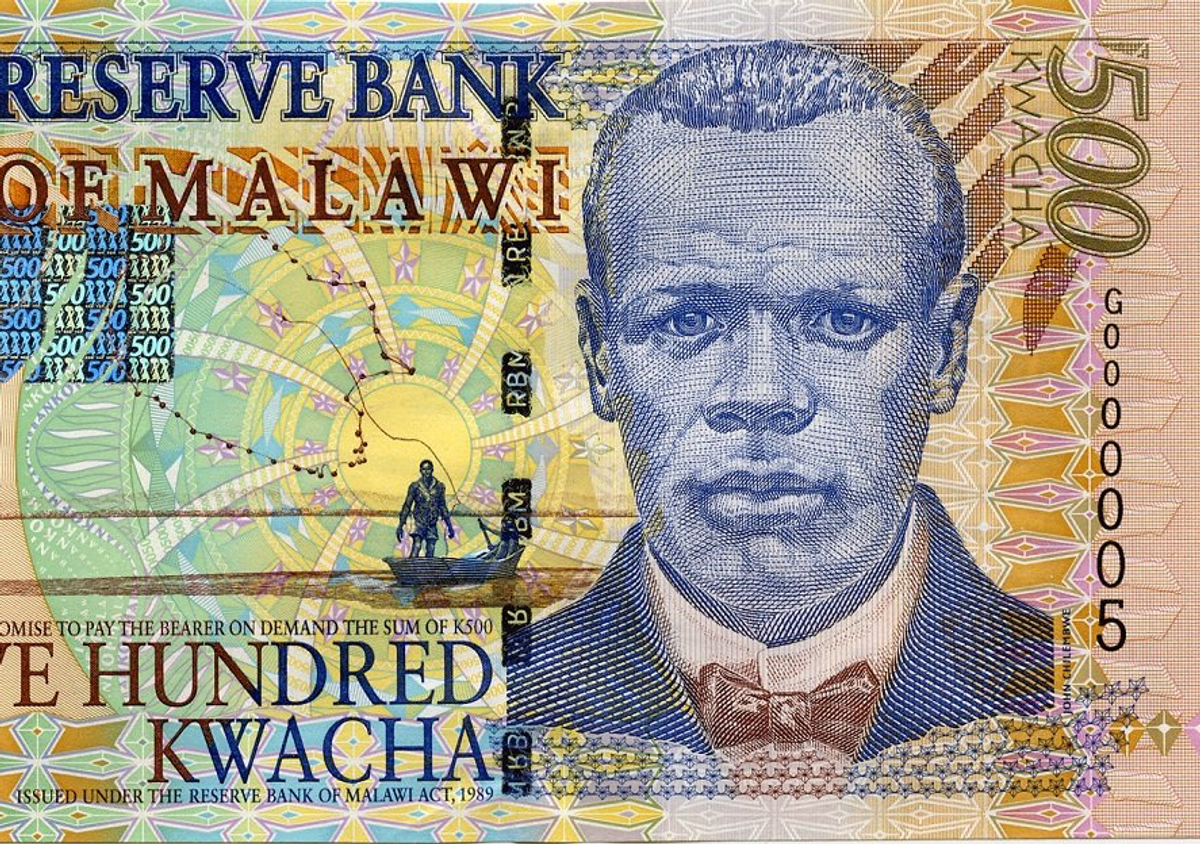

Thursday 15 January John Chilembwe Day in Malawi

John Chilembwe was born sometime between 1860 and 1871 in the African nation of Nyasaland, now known as Malawi. There is no record of his exact date and place of birth.

What is known is that he was trained as a church minister in the United States returning home after becoming a Baptist minister.

While in America he learned about the abolitionist movement there. Back in Malawi, he developed a growing disgust with the wanton cruelty of white rule, especially on white estates that had African tenants and wage earners.

At the start of the first world war, Britain decided to use Nyasa soldiers against the Germans in east Africa. To use locals without their agreement in such a conflict proved to be a tipping point for Chilembwe’s anger against the British.

On Saturday January 23rd 1915, Chilembwe led an uprising and attacked a notoriously brutal estate, killing several managers along with several African workers. One of those killed was Jervis Livingstone and it is said Chilembwe displayed Livingstone’s severed head in his church. Lacking support from other districts, the revolt quickly collapsed. Chilembwe tried to flee to neighbouring Mozambique. He and a group of his followers were caught and killed on February 3rd 1915.

Over the years though, Chilembwe has become a symbol of the country’s liberation struggle against the white colonialists. He was also the first to give a voice to the idea of a Nyasa identity, in this country that was more tribal-based. His enduring popularity was aided by a popular play about his uprising being aired on the radio every year on Martyrs’ Day (March 3rd) in the 1980s and 1990s.